Meavy 1066 and Life in Domesday England

Despite the fact that the Godwin family held vast areas of land in the West Country, it is highly likely that most of the population would have never heard of Harold of Wessex or that when the crown of England was placed upon his head the country’s fate was sealed.

On the 25th of September 1066, three hundred miles away from Meavy in a small village in Yorkshire, a battle took place that would play an important part in shaping England, not Hastings, that was less than a month later, but Stamford Bridge. Five days before the battle, Harald Hardrada and his English ally Tostig Godwinson, brother to the king, took to the River Ouse in their longships with over ten thousand men. Only four days after hearing of this invasion, Harold Godwinson marched the hundred and eighty miles to Yorkshire and surprised the invaders. A fierce battle was fought but eventually the defending English army succeeded in defeating Hardrada's men. Hardrada himself was killed by an arrow in his windpipe and Tostig was cut down with a sword. Two days later, William the Conqueror's invasion force set sail for England landing the very next day at Pevensey Bay in Sussex. Legend states that as the Norman leader set foot on the beach he stumbled and fell, and a collective gasp was heard, knowing that his men believed this to be a bad omen he shouted

On the 25th of September 1066, three hundred miles away from Meavy in a small village in Yorkshire, a battle took place that would play an important part in shaping England, not Hastings, that was less than a month later, but Stamford Bridge. Five days before the battle, Harald Hardrada and his English ally Tostig Godwinson, brother to the king, took to the River Ouse in their longships with over ten thousand men. Only four days after hearing of this invasion, Harold Godwinson marched the hundred and eighty miles to Yorkshire and surprised the invaders. A fierce battle was fought but eventually the defending English army succeeded in defeating Hardrada's men. Hardrada himself was killed by an arrow in his windpipe and Tostig was cut down with a sword. Two days later, William the Conqueror's invasion force set sail for England landing the very next day at Pevensey Bay in Sussex. Legend states that as the Norman leader set foot on the beach he stumbled and fell, and a collective gasp was heard, knowing that his men believed this to be a bad omen he shouted

“See I already have England in my hands.”

When King Harold heard that the Normans had landed on England's shores he began his weary march south with his force of up to thirteen thousand men.

On the day of the battle the Saxon army were well placed, they knew the lay of the land and they stood in closed ranks, shield to shield over seven hundred metres above the enemy line. The day should have been theirs, but as the battle progressed it turned in favour of the Normans. On the 14th of October 1066 the last true English King perished, falling dead to the ground with an arrow to his eye. With hindsight, we now know that Harold's forces were not a match for the Normans, they had no men mounted on horses and the wore no chain mail and they fought from a fixed position. From this point on William of Normandy would be referred to as William the Conqueror.

The autumn of 1066 turned to winter and as the Norman invaders made their way to London, the people of Meavy had finished with the harvest, tithes had been paid and families were preparing themselves for a winter of wind, rain and snow, unaware of the havoc that their new king had in store for the country. They would not have known that the Conqueror had taken all the important cities of England relatively quickly and built castles at York, Nottingham and Lincoln. Major towns were taken, but it took much longer for remote manors such as Meavy to feel the iron fist of the Norman's plunging into the heart of their community. Sadly, those villages that neighboured Hastings and those that lay on the road to England's capital were not so lucky. These villages were attacked almost straight away, their men killed, their women raped and it farms stock seized. The effect of this harrowing on these tiny communities lasted for decades and many never recovered, where there were no men to work the land, villagers simply starved to death.

William the Conqueror faced many rebellions against his rule, it would take him five years of cruelty and viciousness to put down all the revolts, eventually though, the Anglo-Saxons, according to William of Malmesbury, would

“never again, in any battle, made a struggle for liberty, as if the whole of the strength of England had fallen with Harold.”

The new king saw to it that much of England's land was given to Norman barons and when the Saxon's resisted he put them down with relentless severity. The long held Saxon estates and rights of those Englishmen killed at Hastings, and those who fled after the battle, were now in the hands of new Norman overlords. By 1067, William, his wife and his half brothers held a quarter of England, and fifteen of those close to him held one third.

On the day of the battle the Saxon army were well placed, they knew the lay of the land and they stood in closed ranks, shield to shield over seven hundred metres above the enemy line. The day should have been theirs, but as the battle progressed it turned in favour of the Normans. On the 14th of October 1066 the last true English King perished, falling dead to the ground with an arrow to his eye. With hindsight, we now know that Harold's forces were not a match for the Normans, they had no men mounted on horses and the wore no chain mail and they fought from a fixed position. From this point on William of Normandy would be referred to as William the Conqueror.

The autumn of 1066 turned to winter and as the Norman invaders made their way to London, the people of Meavy had finished with the harvest, tithes had been paid and families were preparing themselves for a winter of wind, rain and snow, unaware of the havoc that their new king had in store for the country. They would not have known that the Conqueror had taken all the important cities of England relatively quickly and built castles at York, Nottingham and Lincoln. Major towns were taken, but it took much longer for remote manors such as Meavy to feel the iron fist of the Norman's plunging into the heart of their community. Sadly, those villages that neighboured Hastings and those that lay on the road to England's capital were not so lucky. These villages were attacked almost straight away, their men killed, their women raped and it farms stock seized. The effect of this harrowing on these tiny communities lasted for decades and many never recovered, where there were no men to work the land, villagers simply starved to death.

William the Conqueror faced many rebellions against his rule, it would take him five years of cruelty and viciousness to put down all the revolts, eventually though, the Anglo-Saxons, according to William of Malmesbury, would

“never again, in any battle, made a struggle for liberty, as if the whole of the strength of England had fallen with Harold.”

The new king saw to it that much of England's land was given to Norman barons and when the Saxon's resisted he put them down with relentless severity. The long held Saxon estates and rights of those Englishmen killed at Hastings, and those who fled after the battle, were now in the hands of new Norman overlords. By 1067, William, his wife and his half brothers held a quarter of England, and fifteen of those close to him held one third.

Soon after Hastings the new Norman king was quick to realise the importance of securing the West Country, the first step in achieving this was to take Exeter, the fourth largest city in the country. This town was still controlled by the Godwin family. Harold’s son had fled to Ireland but his mother, Gytha, who still lived within the city walls held out against the Norman forces during William’s return to Normandy, however on his return to England he made Exeter his first port of call. Exeter’s city walls withstood an eighteen month winter siege, many of the Norman soldiers succumbed to the cold, eventually though Exeter fell and Gytha escaped with her granddaughters to island of Flatholme in the Bristol Channel. There is no mention of Harold's son’s at the Siege of Exeter and it may well be that they were already in Ireland. Gytha’s stand at Exeter in 1068 wasn’t the last effort by the Godwins to take back some control of their father's country. Inevitably though, Devon would submit to Norman control, but before that Harold’s sons would give the invaders a run for their money.

Looking over the Taw Estuary towards Appledore, on the left you can see the fields that divide this Devon town from neighboring Northam and on which King Harold's sons fought the Norman invaders

On the 26th June 1069, in the lush green fields that look over the Taw estuary, Godwine and Edmund landed with an invading force in what could be actually be a rematch of the Battle of Hastings. Evidence that has come to light in recent years suggests that this battle took place in the fields that lie in between the villages of Northam and Appledore. The Godwin’s forces arrived from Ireland, on board sixty - four longs ships given to them by the Irish king of Leinster. The defending army was made up of Normans, Bretons and English headed by Brian of Brittany who had fought with the Conqueror at Hastings, following the battle it is thought that more than 3,000 men died in this clash. Brian of Brittany was rewarded with lands in Cornwall, however the fates of the sons Harold is not known.

By 1072 England was completely subjugated and William’s aim now was to consolidate his power, this was achieved by what we know today as the feudal system, a system of government, organised by rank with a set of agreed rules. Of course the medieval person did not talk of a feudal system, in fact the term 'feudal' was used only as far back as the eighteenth century in reference to out of date and unfair laws. The system I learnt at school was a system where the king ruled and protected his country, his barons supplied the knights for the army in times of war and the peasants did all the rest. The fact is this new Norman system was just an extension of the Saxon’s rudimentary system of landholding is often forgotten and it is the Normans that take the credit.

Under this feudal system virtually all of the neighbouring county of Cornwall was granted to William’s half brother Robert, the Count of Mortain, what was left was divided between between minor nobles and the church. Although Mortain's greater land holdings were in Cornwall he did hold land in Devon, he was Lord in ten and Tenant in Chief in sixty-nine, the vast majority of land holdings in the county were held under the FitzGilbert family, the Bishop of Exeter and one Iudhael, a Breton knight who fought for the Norman’s in 1069 and to whom William granted the feudal manor of Totnes.

By 1072 England was completely subjugated and William’s aim now was to consolidate his power, this was achieved by what we know today as the feudal system, a system of government, organised by rank with a set of agreed rules. Of course the medieval person did not talk of a feudal system, in fact the term 'feudal' was used only as far back as the eighteenth century in reference to out of date and unfair laws. The system I learnt at school was a system where the king ruled and protected his country, his barons supplied the knights for the army in times of war and the peasants did all the rest. The fact is this new Norman system was just an extension of the Saxon’s rudimentary system of landholding is often forgotten and it is the Normans that take the credit.

Under this feudal system virtually all of the neighbouring county of Cornwall was granted to William’s half brother Robert, the Count of Mortain, what was left was divided between between minor nobles and the church. Although Mortain's greater land holdings were in Cornwall he did hold land in Devon, he was Lord in ten and Tenant in Chief in sixty-nine, the vast majority of land holdings in the county were held under the FitzGilbert family, the Bishop of Exeter and one Iudhael, a Breton knight who fought for the Norman’s in 1069 and to whom William granted the feudal manor of Totnes.

Seventeen years later in 1086, Iudheal of Totnes, held ninety-seven manors where he was tenant in chief these included four of the five manors of Meavy. The fifth was held by Robert the Bastard, who was tenant in chief of eight other manors in Devon.

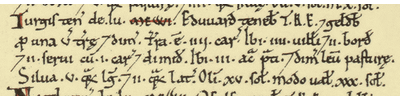

The entry in the Domesday book of one manor of Meavy you can see below.

The entry in the Domesday book of one manor of Meavy you can see below.

Life for my Meavy ancestors in the centuries between their beginnings as an isolated Dumnonii tribe, and the invasion of the Normans would not have changed at all, it was still a hard and meager existence. They would still have hunted and farmed and defended what was theirs, the only difference during those years was who they defended their property from. The Meavy’s may not have heard of the kings who sat on the throne of England, but by the time the Domesday commissioners came knocking at their doors they might not have known who William the Conqueror was, but they would certainly know exactly what he wanted.

The villages that had been ravaged by marauding Norman soldier in the days and weeks after Hastings saw the taxable value of their land fall to half its value in 1086, a direct result of the devastation of twenty years previous. Theses great changes can be viewed in the Conqueror’s great Domesday Book of 1086, where the effect of the invasion on England’s population can be calculated, as can the change of ownership of land. Written in Latin and Roman numerals - the language of the church, the Domesday Book was an evaluation of land for the purpose of tax, it stated who held it and what was on it. When this book was compiled it had no name, but was soon referred to as the Book of Winchester because it was kept in the royal treasury there. By 1170 this great work was popularly called the Domesday Book. Not only did it gather information about the land it was also an attempt to sort out disagreements over what land belonged to whom, and it is here for the first time that we see exactly what land the family of Meavy owned and it is the first time we see Meavy, as a village, written down.

The villages that had been ravaged by marauding Norman soldier in the days and weeks after Hastings saw the taxable value of their land fall to half its value in 1086, a direct result of the devastation of twenty years previous. Theses great changes can be viewed in the Conqueror’s great Domesday Book of 1086, where the effect of the invasion on England’s population can be calculated, as can the change of ownership of land. Written in Latin and Roman numerals - the language of the church, the Domesday Book was an evaluation of land for the purpose of tax, it stated who held it and what was on it. When this book was compiled it had no name, but was soon referred to as the Book of Winchester because it was kept in the royal treasury there. By 1170 this great work was popularly called the Domesday Book. Not only did it gather information about the land it was also an attempt to sort out disagreements over what land belonged to whom, and it is here for the first time that we see exactly what land the family of Meavy owned and it is the first time we see Meavy, as a village, written down.