|

Samuel Purches

4th Great Grandfather 1766 - ? |

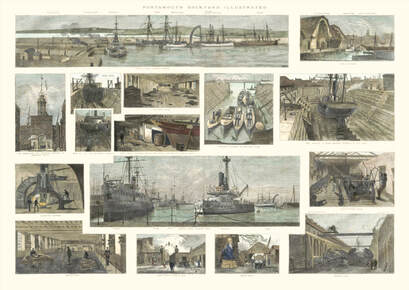

Samuel Purches was born in Portsmouth in 1766 and baptised on the 18th of May at St Thomas’s Church, a stone's throw away from the royal dockyard. During his childhood, Samuel would have seen a harbour full of ships, and as a nine-year-old, he may have witnessed the return of James Cook in his ship the Resolution after circumnavigating the world. A few years later he may have witnessed the departure of the fated HMS Bounty, under the command of William Bligh, on its voyage to acquire breadfruit plants to transport to the West Indies. Samuel's Portsmouth, as we have seen, was a hive of activity, ships sailed in and out of the harbour heading to ports all over the world, and the harbour was a favourite topic of Victorian artists, who all depicted the port in a different way. Edward G Burrows painting of Portsmouth Harbour is overly romantic, while Ambroise Louis Garneray’s painting shows us the habour in a very different light.

Two other artists, George Morland and Luke Clenell depict how dangerous life was in Portsmouth for men like Samuel and his father, their artworks depict impressment, a practice that was widely used by Britain's Royal Navy as a means to maintain crew numbers on its warships. This use of force was in place as far back as the 13th century and was common practice from the mid-16th century being legalised in the reign of Elizabeth I.

In Portsmouth, the area of Spice Island, which was separated from the town itself by King James’s Gate, was a favourite recruiting area for press gangs. It was full to bursting with eating houses, drinking establishments, pawn shops, brothels, and all manner of services that were frequented by many of the inhabitants of Portsmouth. Impressment was enforced by a press gang - when a man was seized he was offered the King's shilling as a reward for volunteering, but often the coin was issued in devious and underhanded ways, such as slipping the shilling into a pocket or dropping it into his drink. It is for this reason that glass-bottomed tankards became popular, you could check your drink didn't contain a shilling before drinking it. Certain groups of men were exempt from the impressment process, apprentices were one category, also there was an age limit which ranged from 18 to 55 years, but the rules were often ignored. Often men were knocked unconscious or threatened and often violent fights broke out, as a young man in the 1780’s I have to wonder if Samuel ever witnessed the violence or worse still did he suffer at the hands of these ‘navy officials.’

As mentioned in a previous chapter, the Purches’ had moved from Portsea to Portsmouth in the years between 1763 and 1766 and were living there until 1770, they returned to Portsea when Samuel was four. Despite moving to Portsea it is highly likely that when Samuel was old enough to work he was employed at the docks in a job that was associated with the sea. With this in mind, maybe he was one of the first people to see Scottish engineer James Watt’s steam engines in use in the dockyard, or he may have crossed paths with Marc Brunel, the father of Isambard Kingdom Brunell, whose design for machinery to mechanise the process of pulley blocks, a device used for rigging and gun carriages that would be put to good use at the docks. Sadly though, there are no records to say what Samuel Purches did for a living, and again we have to view Samuel's life through the world about him.

Portsmouth in the years of Samuel’s birth, according to Daniel Defoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe, had become an increasingly unpleasant place to live, but he described Portsea as being like a suburb, a slightly better place to live, due in part to the ‘beauty of the buildings.’ In reality though it was a different story, like Portsmouth the town was a breeding ground for all sorts of diseases, it had cramped streets, poor living conditions, and no drainage, and rubbish on the streets was causing much distress among the population. By 1764, some attempt at improving the situation was made when Improvement Commissioners were appointed. These men had the power to oversee the paving and cleaning of the streets, also appointed was a scavenger, a man who collected rubbish once a week. Portsea in 1770 was a different place from the one Samuel’s father had settled in just ten years previously, but despite some changes, living conditions for the poorest families were still dire. As time moved on, Portsea’s streets, with their new buildings, inns, lodging houses, and shops became linked with that of Portsmouth itself. In 1792, despite the encroachment of the naval town, this self-sufficient community had grown into a town in its own right and was given the name of Portsea. Eventually though, the high wall that enclosed Portsmouth was extended to include Portsea and bound the town on two sides, a slipway known as Hard covered the third side.

Portsmouth in the years of Samuel’s birth, according to Daniel Defoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe, had become an increasingly unpleasant place to live, but he described Portsea as being like a suburb, a slightly better place to live, due in part to the ‘beauty of the buildings.’ In reality though it was a different story, like Portsmouth the town was a breeding ground for all sorts of diseases, it had cramped streets, poor living conditions, and no drainage, and rubbish on the streets was causing much distress among the population. By 1764, some attempt at improving the situation was made when Improvement Commissioners were appointed. These men had the power to oversee the paving and cleaning of the streets, also appointed was a scavenger, a man who collected rubbish once a week. Portsea in 1770 was a different place from the one Samuel’s father had settled in just ten years previously, but despite some changes, living conditions for the poorest families were still dire. As time moved on, Portsea’s streets, with their new buildings, inns, lodging houses, and shops became linked with that of Portsmouth itself. In 1792, despite the encroachment of the naval town, this self-sufficient community had grown into a town in its own right and was given the name of Portsea. Eventually though, the high wall that enclosed Portsmouth was extended to include Portsea and bound the town on two sides, a slipway known as Hard covered the third side.

Samuel Purches grew from a boy to a man in Portsea in the area around Squeeze Gut Alley, so named because the streets and houses were too close together, but by 1775 one writer stated that Portsea had moved on from ‘a barren, desolate heath to a very populous, genteel town, exceeding Portsmouth itself in the number of its inhabitants and edifices’ By 1789, Samuel had met and married Elizabeth Cousins who was probably born in Alverstoke, a small town across the water from Portsea. Women in the Georgian period, regardless of their social class, were at the mercy of their husbands, their social situation, and fate - they would always be someone's daughter, wife, or mother, this one entry for Elizabeth is one of a few times we see her as an individual. Samuel and Elizabeth’s marriage took place on the 7th of July at St Mary’s Church in Alverstoke. Within eighteen months their first child was born, a girl they named Mary, she was baptised at St Marys in Portsea on the 10th January 1791. By the June of the following year, Elizabeth was pregnant again and in the February of 1793 their daughter Anne was born, but the poor child was dead within seven months. Within another seven months tragedy struck the family again when three-year-old Mary died. The cause of the death of Mary and Anne is unknown but doctors were scathing about the conditions that families had to live in. In 1795, a Dr George Pinckard visited Portsmouth, he described it as "crowded with a class of low and abandoned beings’, and just a few years later the town was described as "one huge cesspool - 160000 cesspools daily permitting 30000 gallons of urine to penetrate the soil." and as "deficient in every requisite to health, comfort, and cleanliness." Is it any wonder these babies did not survive?

When Elizabeth stood at Mary’s graveside she was already six months pregnant.

When Elizabeth stood at Mary’s graveside she was already six months pregnant.

Society had abandoned the likes of Samuel and Elizabeth, with no medical care all they had was the power of prayer. Perhaps Samuel and Elizabeth did pray, for in August Elizabeth had given birth to their son who they named James.

Following James’s birth, there was a four-year gap before the birth of a daughter. This little girl has named Mary Ann, her naming is a testament to how deeply they felt about the loss of their first two daughters. The gap between the births of James and Mary Ann is significant, because previous to the birth of their last child Elizabeth had given birth at regular intervals. This is not unusual, but it might signify that either Elizabeth miscarried during those years or simply that Samuel was away from home - a stint at sea maybe? After that Samuel and Elizabeth's last four children appeared every two years, Thomas in the April of 1801, William Samuel, my 3x great grandfather in the March of 1803, Elizabeth in the March of 1805, and finally Sophia in 1807. The three youngest children were born during the Napoleonic Wars, a series of conflicts between 1803 and 1815 which pitted the French and their allies led by Napoleon Bonaparte against a European coalition led by the United Kingdom.

What is known as the Third Coalition began in 1803, it was the first of the Napoleonic Wars and it's most famous. Napoleon was keen to see the United Kingdom out of the war, to do this he amassed a huge army, but if he had any chance of succeeding he had to take out Britain's Royal Navy. However, the French navy was not a patch on the English, and by 1805 the English defeated the combined forces of the French and the Spanish at the Battle of Trafalgar under the command of Horatio Nelson, this famous battle was the last significant naval action of the war.

Following James’s birth, there was a four-year gap before the birth of a daughter. This little girl has named Mary Ann, her naming is a testament to how deeply they felt about the loss of their first two daughters. The gap between the births of James and Mary Ann is significant, because previous to the birth of their last child Elizabeth had given birth at regular intervals. This is not unusual, but it might signify that either Elizabeth miscarried during those years or simply that Samuel was away from home - a stint at sea maybe? After that Samuel and Elizabeth's last four children appeared every two years, Thomas in the April of 1801, William Samuel, my 3x great grandfather in the March of 1803, Elizabeth in the March of 1805, and finally Sophia in 1807. The three youngest children were born during the Napoleonic Wars, a series of conflicts between 1803 and 1815 which pitted the French and their allies led by Napoleon Bonaparte against a European coalition led by the United Kingdom.

What is known as the Third Coalition began in 1803, it was the first of the Napoleonic Wars and it's most famous. Napoleon was keen to see the United Kingdom out of the war, to do this he amassed a huge army, but if he had any chance of succeeding he had to take out Britain's Royal Navy. However, the French navy was not a patch on the English, and by 1805 the English defeated the combined forces of the French and the Spanish at the Battle of Trafalgar under the command of Horatio Nelson, this famous battle was the last significant naval action of the war.

Over an eleven-year period, under Nelson's leadership, the Royal Navy proved its superiority over the French, tragically, Trafalgar would be Nelson’s last command. Before the battle, which took place on the 21st of October in 1805, Nelson sent out his famous signal to his fleet 'England expects that every man will do his duty’ Horatio Nelson led from the front, but he was killed while leading the attack on the enemy fleet. His body was preserved in brandy and transported back to England where he was given a state funeral. Lord Byron referred to Horatio Nelson as ‘Britannia's God of War’ even today, quite rightly, he is regarded as the greatest officer in the history of the Royal Navy. Nelson was born in Norfolk at Burnham Thorpe, either by coincidence or association, this tiny East Anglian village would figure in the life of Samuel’s son William.

Despite the poverty and the doom and gloom brought about by the war Samuel and Elizabeth managed to survive, and Elizabeth at least lived long enough to see their children married, five of the six children were married between 1818 and 1830, only Sophia, the youngest child is unaccounted for, and between four of these, Samuel and Elizabeth became grandparents to twenty-five children. It is through the lives of his children that we can, for the first time, say with some certainty where Samuel and Elizabeth were living. It was on Bonfire Corner, in the commercial area of Portsea, that Samuel and Elizabeth lived the last years of their lives.

Bonfire Corner, so called because it is thought that rubbish from the dockyard was burnt here, is separated from the Royal Dockyard by an imposing red brick wall that was begun in 1704 and finished in 1711. Bonfire Corner begins where it joins Admiralty Road, which was where the former entrance to the Academy, now blocked was once situated. Bonfire Corner runs about five hundred yards and ends, like the wall at Marlborough Gate. Samuel and Elizabeth must have walked along this road and past this wall hundreds of times, because where naval office buildings now stand were the shops, inns, and houses that the family must have frequented. The whole extended family can be found on Bonfire Corner in 1841, and on the same census, we can see exactly what the family were doing for a living. James, Samuel’s eldest son was a shipwright, Thomas a grocer, Elizabeth’s husband was a sawyer, and Mary Ann’s husband was a soldier in India. Elizabeth is here too, she is stated to be a lodging housekeeper. Despite every one of them being employed life was still a struggle, a glimpse of how they and other families were living is explained in Robert R Dolling’s Ten Years in a Portsmouth Slum - it makes grim reading:

‘The wages of the majority of people in regular employment were so small that they lived in constant poverty, the larger parts had no settled wages at all, many of them being hawkers, greengrocers with a capital of five shillings, window cleaners in a district where nobody wanted their windows cleaned, old pensioners past work with a shilling of eightpence a day, sailors wives with three of four children living upon two pounds a month and soldiers wives married off the strength with no pay at all.’

‘The wages of the majority of people in regular employment were so small that they lived in constant poverty, the larger parts had no settled wages at all, many of them being hawkers, greengrocers with a capital of five shillings, window cleaners in a district where nobody wanted their windows cleaned, old pensioners past work with a shilling of eightpence a day, sailors wives with three of four children living upon two pounds a month and soldiers wives married off the strength with no pay at all.’

Not only did the likes of the Purches’ have to put up with poor living conditions and poverty but they were confronted with class prejudice too. Where the dockyard wall separated Portsea Town from the military base a class barrier separated the working class from the middle class, Robert Dolling wrote of the effects of this too, stating that ‘it was hard to create a united city’ - such was the middle-class prejudice, that one wealthy family would attempt to ‘put a stop to the mingling of classes around his premises’ by attempting to build a barrier. Did any of the Purches take part in the riot that took place when the barrier was pulled down I wonder?

Elizabeth, as mentioned was a lodging housekeeper and she is stated as being aged seventy-five, and there is no mention of Samuel, and therefore, we must assume that he had died. Samuel Purches death occurred before civil registration, and I can find no record of his death or where he was buried, but if he died in Portsea it is likely that he is buried in the churchyard of St Mary’s.

Once again, I am forced to repeat myself and say we have to look at Samuel through the events that were happening around him, his legacy though was his children and through them, we get a greater, more personal look at who the Purches was. James, Thomas, Mary Ann, and Elizabeth were destined to live and die in Portsea however, William Samuel, the youngest son was the only one to leave the island for a life on the mainland - however, it was still a life connected to the sea.

Elizabeth, as mentioned was a lodging housekeeper and she is stated as being aged seventy-five, and there is no mention of Samuel, and therefore, we must assume that he had died. Samuel Purches death occurred before civil registration, and I can find no record of his death or where he was buried, but if he died in Portsea it is likely that he is buried in the churchyard of St Mary’s.

Once again, I am forced to repeat myself and say we have to look at Samuel through the events that were happening around him, his legacy though was his children and through them, we get a greater, more personal look at who the Purches was. James, Thomas, Mary Ann, and Elizabeth were destined to live and die in Portsea however, William Samuel, the youngest son was the only one to leave the island for a life on the mainland - however, it was still a life connected to the sea.