Samuel was born at the very beginning of what is known as the Regency Period. In the February of 1811, a month before the birth of Samuel, George, Prince of Wales had become Regent of England. His father, King George III had been on the throne for fifty one years but had suffered bouts of mental illness and was thought to be insane. In the same month, but closer to home, the transport ship the John and Jane was accidentally run into and sunk by HMS Franchise off Lizard Point with the loss of two hundred and twenty four lives. National events and county catastrophes would more than likely have gone unnoticed by the Mitchells, they would have been too busy in their own world. The new farming year was just about to start and with the birth of Samuel there was yet another mouth to feed.

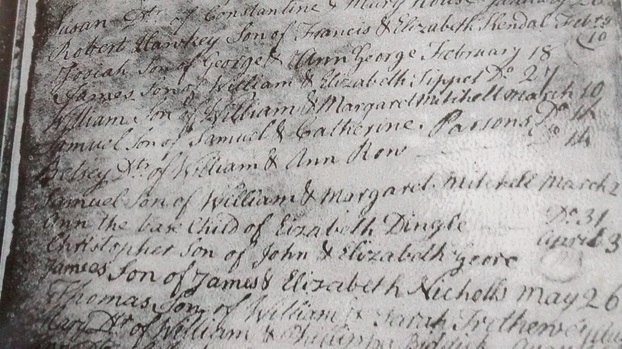

Samuel was the eighth child born on the farm at Lescliston, he was baptised at Crantock Parish Church on the 24th March 1811, his entry in the register is the eighth entry on image below .

Samuel was the eighth child born on the farm at Lescliston, he was baptised at Crantock Parish Church on the 24th March 1811, his entry in the register is the eighth entry on image below .

Seventy years had passed since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, Cornwall’s famous son Richard Trevithick had been in Peru since 1816 and there was talk in the county him neglecting his wife. Trevithick’s new agricultural methods that helped feed the large non agricultural population but it had also caused it to increase. By 1821, the year of Samuel's tenth birthday, the population of England had reached fourteen million, many of them uneducated children. In 1818, one John Pounds opened a school in Portsmouth and began teaching poor children reading, writing and arithmetic and in 1820 one Samuel Wilderspin opened the first infant school in London. Like the vast majority of children in England Samuel had no formal education, this was reserved for a minority, all Samuel needed to know he learnt on his parents farm. Sunday School would probably the best he could hope for, but these ‘schools’ stressed a religious education. There was little chance of Samuel gaining a secular education, but this did not mean that Samuel was uneducated, at some point he had learnt to write, for the entry of his marriage in the parish register was signed by him.

Samuels early life appears to be uneventful, his days were spent on the farm surrounded by his siblings, helping prepare the land for the new year and harvesting the crops at the end of it, this was the life of a farmer and as such Samuel's life was governed by the seasons. There would be times when there was much to do and few times when there was nothing. I wonder when he did have time to himself, if he thought life was passing him by, and it certainly seems that way, by the time of the 1851 census, he was forty-one and unmarried. I’ve always felt that Samuel was a sad man, there is no reason I should think this way and neither do I have evidence to back it up, I only have a gut feeling. In my minds eye he was always alone tending the fields in the far corner of his father’s holding, at those times I imagine he would think of his mother who died in 1833, of his married sisters, living somewhere else other than an isolated farm tenement with an aging father and an older brother and sister who too were unmarried.

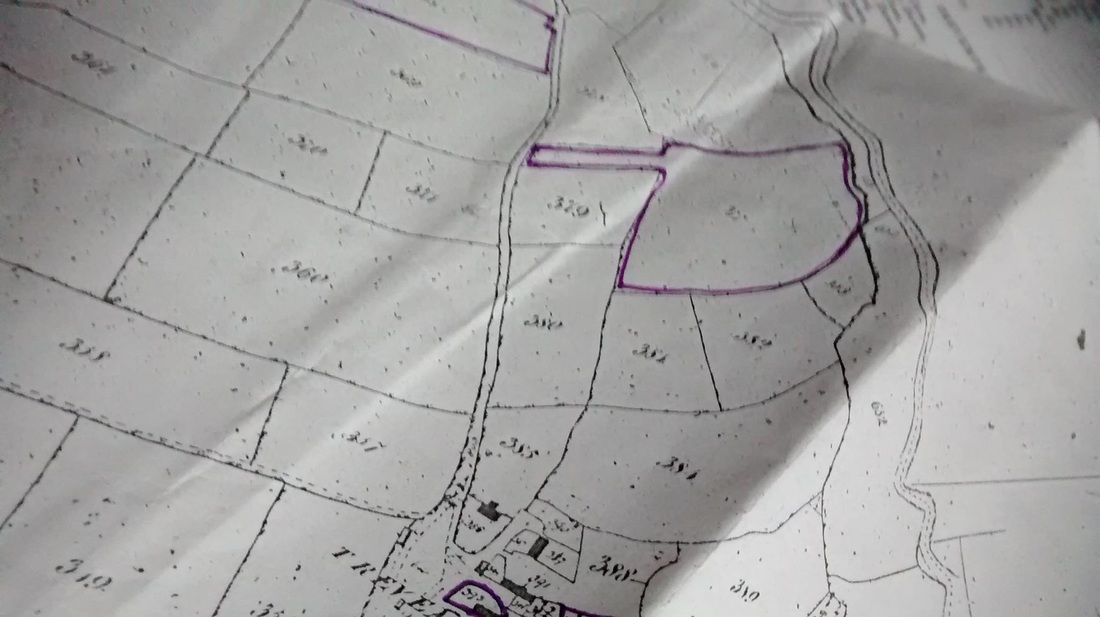

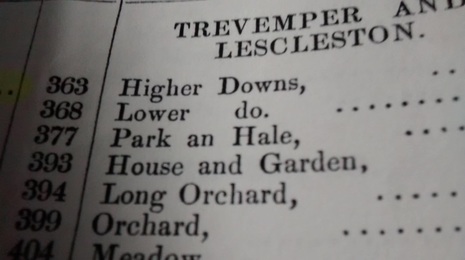

Three of the fields that made up Samuel fathers farm at Trevemper overlooked the Gannel towards Penpol, one of these fields was named Park an Hale, on the map below the Clemens boatyard at Tregunnel is just out of view but you can see the Park an Hale field, marked here as number 377, just below the bend in the river.

Samuel, no doubt, would stop for a break and gaze over the Gannel in the direction of Newquay, in doing so he would be able to see the above mentioned boatyard, owned by Thomas Clemens. Looking down the hill he would be able to see the 95-ton schooner The Tower that was being built at the yard and hear the chatter of the Clemens brothers as they went about their work.

Samuels early life appears to be uneventful, his days were spent on the farm surrounded by his siblings, helping prepare the land for the new year and harvesting the crops at the end of it, this was the life of a farmer and as such Samuel's life was governed by the seasons. There would be times when there was much to do and few times when there was nothing. I wonder when he did have time to himself, if he thought life was passing him by, and it certainly seems that way, by the time of the 1851 census, he was forty-one and unmarried. I’ve always felt that Samuel was a sad man, there is no reason I should think this way and neither do I have evidence to back it up, I only have a gut feeling. In my minds eye he was always alone tending the fields in the far corner of his father’s holding, at those times I imagine he would think of his mother who died in 1833, of his married sisters, living somewhere else other than an isolated farm tenement with an aging father and an older brother and sister who too were unmarried.

Three of the fields that made up Samuel fathers farm at Trevemper overlooked the Gannel towards Penpol, one of these fields was named Park an Hale, on the map below the Clemens boatyard at Tregunnel is just out of view but you can see the Park an Hale field, marked here as number 377, just below the bend in the river.

Samuel, no doubt, would stop for a break and gaze over the Gannel in the direction of Newquay, in doing so he would be able to see the above mentioned boatyard, owned by Thomas Clemens. Looking down the hill he would be able to see the 95-ton schooner The Tower that was being built at the yard and hear the chatter of the Clemens brothers as they went about their work.

The Clemens were a local family from Newquay whose patriarch was John Clemens, he had three sons James, Richard and Thomas. James, his elder son, had a daughter, the indomitable and self assured Johanna, who was six years younger than Samuel and like Samuel was still unmarried.

In 1841 there were just over one hundred families living in Newquay, with such a small population there would be few suitable marriage partners, but Samuel and Johanna, both in their thirties, were perfect for each other. How the couple met it not known, the Mitchells would have known the Clemens, Samuel could have wandered down to the shipyard to talk to men as they worked, maybe they met through Johanna’s cousin John Clemen’s, who managed a public house in Newquay or they may have even met at the celebrations around the launch of the the schooner when it was finally finished in 1851. However, meet they did, and by end of October 1852, Samuel and Johanna Clemens were married.

In 1841 there were just over one hundred families living in Newquay, with such a small population there would be few suitable marriage partners, but Samuel and Johanna, both in their thirties, were perfect for each other. How the couple met it not known, the Mitchells would have known the Clemens, Samuel could have wandered down to the shipyard to talk to men as they worked, maybe they met through Johanna’s cousin John Clemen’s, who managed a public house in Newquay or they may have even met at the celebrations around the launch of the the schooner when it was finally finished in 1851. However, meet they did, and by end of October 1852, Samuel and Johanna Clemens were married.

The couple’ s marriage took place the Church at St Columb Minor and was soon followed by the birth of their first child, nine days short of their first wedding anniversary. Edith’s birth entry has the family living at Trevemper, it seems that instead of moving back into the family home at Lescliston, Samuel resided at Trevemper farm which is situated just over a hundred yards from Trevemper bridge. At two year intervals, four more children were born to Samuel and Johanna, William in 1855, Samuel in 1856, James in 1859 and Albert in 1860. In 1857, William, Samuel’s father died, the land that had been farmed by the Mitchell’s stayed within the family but was divided between James, who kept fifty acres at Lescliston, and Samuel who received thirty acres, the ten remaining acres passed to another farmer in the area, maybe it was taken by Zacchaeus Prater or Constantine House, these families lived in close proximity to the Mitchell's, they had had a connection (by marriage) to the Mitchell's since 1845.

Cornish farms comprised of a main farmhouse and one or two smaller buildings serving as barns and animal houses just as you can see in the above images of Trevemper Farm. These buildings were laid out with a long axis that ran down slope for drainage purposes. The soil on Samuel's farm was rich, so he may have planted wheat and tilled the soil with a ox drawn plough.

Evidence of this comes from the reminiscences of a young girl, later to be known as Sarah Teage Husband, who grew up in Newquay and wrote of watching a farmer till his soil, the plough pulled by an ox, on or near Trevemper. She dates her memories to between 1850 and 1860, this would make her about the same age as Samuels daugther Edith. In 1923 she wrote

“The driver who attended to them would sing some kind of refrain in time with their rhythmic gait, calling each oxen by its name and using a long goad when necessary to accelerate their movements”

A goad is a pole, six or seven feet long with a point at the end that Husband said appeared to be a very effective instrument for the purpose it was intended. Husband insight into the activities of the farming community at Crantock are very interesting especially when she writes about harvest time.

Evidence of this comes from the reminiscences of a young girl, later to be known as Sarah Teage Husband, who grew up in Newquay and wrote of watching a farmer till his soil, the plough pulled by an ox, on or near Trevemper. She dates her memories to between 1850 and 1860, this would make her about the same age as Samuels daugther Edith. In 1923 she wrote

“The driver who attended to them would sing some kind of refrain in time with their rhythmic gait, calling each oxen by its name and using a long goad when necessary to accelerate their movements”

A goad is a pole, six or seven feet long with a point at the end that Husband said appeared to be a very effective instrument for the purpose it was intended. Husband insight into the activities of the farming community at Crantock are very interesting especially when she writes about harvest time.

“When the last sheaf was cut, the reaper held it up and shouted “I have’en. I have’en. I have’en.” The others who stood around answered, “We have’ee, We have’ee. We have’ee “ and the reaper replied “Anek! Anek! Anek! Then they all shouted “Hurray!”

This farming ritual, known as “Cry the Neck” would have been performed by Samuel and his family, and it may be that it was on Samuel’s farm that she witnessed it.

While Samuel was holding the last bundle of wheat high, Johanna and the other wives would be preparing for the harvest celebrations that were usually held in the loft of a barn. This west country tradition was known as a Troyl, a word taken from the Cornish word troillia meaning to twist, twirl, whirl or spin round. Again, we can rely on the wonderful recollections of the young Newquay girl to supply us with a picture of the festivities:

“Dancing and games followed, the music was provided by a fiddler; the dances were folk dances which kept all up to the small hours of the morning.”

This farming ritual, known as “Cry the Neck” would have been performed by Samuel and his family, and it may be that it was on Samuel’s farm that she witnessed it.

While Samuel was holding the last bundle of wheat high, Johanna and the other wives would be preparing for the harvest celebrations that were usually held in the loft of a barn. This west country tradition was known as a Troyl, a word taken from the Cornish word troillia meaning to twist, twirl, whirl or spin round. Again, we can rely on the wonderful recollections of the young Newquay girl to supply us with a picture of the festivities:

“Dancing and games followed, the music was provided by a fiddler; the dances were folk dances which kept all up to the small hours of the morning.”

The occasions that Samuel and Johanna took part in the festivities their children were only small, no doubt tucked up in bed and the family servant watching over them. With the harvest of 1861 safely in, and the party in full swing I like to think that this was a happy time for Samuel, he had farmed at Trevemper for four years and his family was complete, his last child, Albert, had been born the previous year. But sadly, during the following the seven years the Mitchell family circumstances changed, by 1868 Samuel was no longer a farmer working the family farm at Trevemper.

This change was possibly the result of Samuel's deteriorating heath, he had lost weight, had a poor appetite, his breathing was laboured, and his legs also were quite swollen, but I feel there was more to it than this, however, Samuel was dead by the end of October. His cause of death was kidney disease. The woman present at Samuel's death was also the informant, she was Mary Rundle, a farmers wife of Trencreek, and according to his death certificate Samuel was living at Trencreek on the day he died. It was also stated that Samuel's occupation was a general labourer.

As I have previously stated, I believe Samuel to have been a sad and unhappy man, he was ill and the family had just recovered from the death of Albert who had died before his eighth birthday, his three remaining sons, who were all under thirteen, meant that they were forced to give up the farm tenancy this could be a reason why Samuel's family can be found living in a cottage at Trenance in 1871. If Samuel's illness was the reason the farm was given up then I wonder why he continued with the back breaking job of labouring, but needs must, and it is probable that it was on Mary's husbands farm that Samuel lived and worked.

The hamlet of Trencreek is just under a mile from Trenance where the family lived, I find it quite strange that Samuel died away from home and his wife was not with him when he took his last breath or at least notified the authorities of it. Again, just like I have no proof of Samuel's character, I have no proof that he was not living at the family home for any other reasons than the Trencreek farm was his place of work, it was not unusual for labourers to live on the farm, but not when their home and family were literally down the road.

It would not surprise me to find out that Samuel left the family home feeling that he could not cope with the demands of running a farm, with Johanna, the death of his son and his ill health. Samuel was dead at the age of fifty six.

This change was possibly the result of Samuel's deteriorating heath, he had lost weight, had a poor appetite, his breathing was laboured, and his legs also were quite swollen, but I feel there was more to it than this, however, Samuel was dead by the end of October. His cause of death was kidney disease. The woman present at Samuel's death was also the informant, she was Mary Rundle, a farmers wife of Trencreek, and according to his death certificate Samuel was living at Trencreek on the day he died. It was also stated that Samuel's occupation was a general labourer.

As I have previously stated, I believe Samuel to have been a sad and unhappy man, he was ill and the family had just recovered from the death of Albert who had died before his eighth birthday, his three remaining sons, who were all under thirteen, meant that they were forced to give up the farm tenancy this could be a reason why Samuel's family can be found living in a cottage at Trenance in 1871. If Samuel's illness was the reason the farm was given up then I wonder why he continued with the back breaking job of labouring, but needs must, and it is probable that it was on Mary's husbands farm that Samuel lived and worked.

The hamlet of Trencreek is just under a mile from Trenance where the family lived, I find it quite strange that Samuel died away from home and his wife was not with him when he took his last breath or at least notified the authorities of it. Again, just like I have no proof of Samuel's character, I have no proof that he was not living at the family home for any other reasons than the Trencreek farm was his place of work, it was not unusual for labourers to live on the farm, but not when their home and family were literally down the road.

It would not surprise me to find out that Samuel left the family home feeling that he could not cope with the demands of running a farm, with Johanna, the death of his son and his ill health. Samuel was dead at the age of fifty six.

By the 1st of November 1868, only eleven years after he buried his father in the cemetery at Crantock, Samuel too was being carried through the churches covered gate.