|

Walter Hendley

1499 - 1550 |

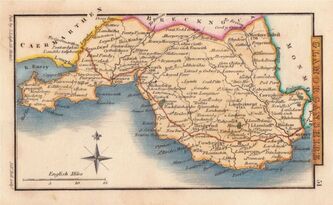

Walter Hendley was born in Kent, a county that was no stranger to battles and rebellions, in the six hundred years between 455 and 1066 there were only three battles and they took place under twenty miles from the Hendley’s manor at Coursehorn. The last, but not strictly in Kent, was the Battle of Hastings, fought just twelve miles south of Coursehorn. In 455, a battle between the Anglos-Saxons, led by Hengist and Horsa against Vortigern, the King of the Britons, was fought at Aylesford and then some three hundred years later, in 776 there was the Battle of Otford fought between the Jutes and the invading Mercians. Of the Kentish rebellions, it is known that men from the area around Coursehorn did take part, two were executed for their part in the Peasants Revolt and as mentioned in a previous chapter Walter Hendley’s great grandfather took part in Jack Cade's rebellion, however, of the five rebellions in the first twelve years of Henry VII’s reign, the men of Kent were not involved en masse. Considering the reasoning behind the aforementioned Peasants Revolt and the Cade Rebellion was tax and local grievances, it was a surprise to discover that despite Thomas Flamank hoping to raise support for his rebellion in the county, Kent did not support these Cornish Rebels in their cause. The county had moved on politically and socially, and its people had learnt their lesson, there was no need for a rebellion based on economics and even less of a reason to help those who did. Henry VII had learnt his lesson too, in the last decade of his reign he summoned parliament only once and he would impose no direct parliamentary taxation, but without parliament the contact between him and his subjects was weakened leaving the king to rely on those men who had proved their loyalty in the early years of his reign.

In Kent, two families in particular were loyal to Henry and both had great power and influence in the county, they were the Guildfords at Benenden and the Neville’s at Mereworth. In one way or another their actions affected the lives of the Hendleys. John and Richard Guildford had supported Henry’s rise to power. George Neville, Baron Bergavenny and his neighbour John Brook, Baron Cobham had been supporters of Richard III, however they changed their allegiances following the Buckingham Rebellion of 1483, their reasons for siding with the new Tudor regime are unknown but it is probable that both men felt they were not justly rewarded by Richard in their support during the Buckingham Rebellion or for their work in keeping Kent under Yorkist control during Richard’s two year reign. Both men were rewarded, Cobham was granted lands in Devon, Cornwall and in Kent, but it would seem the rewards granted to Bergavenny were not enough. By 1497 both men could be found fighting alongside Guildford against the Cornish rebels after which Neville was rewarded with a number of important positions, however it seems he may have been envious of Richard Guildford being made a Banneret, a title that can only be conferred by the sovereign on the field of battle. George Neville had three character flaws, he was greedy and resentful (he was aggrieved because the king had taken no action in removing the heir of his cousin Richard Neville from land he considered his by right,) but in regard to Richard Guildford he was just plain jealous - the origins of which, as we have just seen, began on the battlefield of Blackheath.

The Nevilles were not a Kentish family, they were nowhere to be seen in the Weald until the reign of Henry VI and more importantly they were seriously outshined by their more famous cousins. The Guildford’s however, had been prominent and influential in the Weald from the early part of the 15th century and had been members of the royal court since the time of Edward IV, add to this that Richard Guilford himself had links, via his wife's family to the Beauforts, and had worked gathering information under Sir Reginald Bray to help place Henry Tudor on the throne. After the failed Buckingham Rebellion, Guildford had escaped to France and then returned with Henry when he landed in Wales in 1485 and from then he became a prominent member of Henry court, all this laid heavy with George Neville, but what Neville really resented was that Guildford’s power within Kent eclipsed his own. With all this in mind, and with Henry VII’s weakened grasp on the nation, the stage was set for trouble in the Home Counties. By joining forces with the aforementioned Baron Cobham, George Neville took steps to build up his own power base by taking advantage of Guildford's slow slide into obscurity by infiltrating Guildford’s spy network and stealing away his retainers from right under his nose.

Under previous kings, retaining was permitted because the monarch accepted that families like the Guildford’s and the Neville’s needed a strong retinue, not only to assert their own authority locally, but to assist him in times of crisis and in war, enabling him to guarantee stability within his kingdom. However, illegal retaining was one problem that dogged Henry’s last few years as king. Historians believe that personally he had no problem with retaining, but as king he condemned the practice, outlawing it in 1504 when men, such as Neville used it to advance his position by use of arms, thus those with the power, the means and personal influence became a law unto themselves, and in 1503 Cranbrook and the Weald experienced the fallout of such behaviour when George Neville exploited Guildford’s financial difficulties by recruiting men from his retinue into his own private army, the result of which saw violent and lawlessness increase in the areas around the Guildford’s estate in Hemsted, which was just five miles from the Hendley’s manor at Coursehorn. George Neville was indicted, fined and banned from Kent, but the feud between the families continued into the second decade of the 16th century. Walter’s grandfather was directly involved in the Suffolk Conspiracy of 1503 but the extent of Walter’s father’s involvement goes unrecorded, but I have no doubt that was some complicity as the connection between the Hendley’s and the Guilford's can be traced as far back at least two generations to the time of Edward Guildford, a thug who was not averse to using violence and menace to get what he wanted.

So, the stage is set for the arrival of Walter, the last male ancestor in the direct line of the Hendley family in Coursehorne in Kent.

Walter Hendley was just four years old when the Guildford and Neville feud was at its peak, we don’t know if men wearing George Neville’s livery ever made trouble in Coursehorne, or if there was an attempt made to gain Walter’s father’s support. Walter, of course, would have been too young to have known of his maternal grandfather's part in it, but it was certainly a dangerous time for anyone who got themselves mixed up with Tudor nobles with big ambitions, and Walter’s parents, especially his mother, knew all too well that the consequences of taking sides could cost a family dearly. We can only wonder if Elizabeth chose to distance herself from her father, who she would rightly suspect was up to his neck in a new plot. Walter Roberts’ Glassenbury estate, as far as Elizabeth may have been concerned, was far enough away that she could keep her family out of harm's way if his world came tumbling down.

Walter Hendley was just four years old when the Guildford and Neville feud was at its peak, we don’t know if men wearing George Neville’s livery ever made trouble in Coursehorne, or if there was an attempt made to gain Walter’s father’s support. Walter, of course, would have been too young to have known of his maternal grandfather's part in it, but it was certainly a dangerous time for anyone who got themselves mixed up with Tudor nobles with big ambitions, and Walter’s parents, especially his mother, knew all too well that the consequences of taking sides could cost a family dearly. We can only wonder if Elizabeth chose to distance herself from her father, who she would rightly suspect was up to his neck in a new plot. Walter Roberts’ Glassenbury estate, as far as Elizabeth may have been concerned, was far enough away that she could keep her family out of harm's way if his world came tumbling down.

Walter was born before 1499, the same time as his aforementioned grandfather had become a father to his ninth child. Walter’s older sister Margaret was born in 1494, and he may have had another sister named Catherine who was born in 1496. I have been unable to trace her; it could be that she succumbed to the sweating sickness that had resurfaced in 1502. Walter’s mother gave birth five more times in the years before Walter’s tenth birthday, and of these new siblings only William, Thomas and Mercy survived. These five children were probably the first Hendley offspring to be raised in a home that could be described as comfortable. Walter, William and Thomas also were the first to benefit from a formal education being taught at home by a tutor, they would have learnt to write by copying the alphabet and the Lord's Prayer. Margaret and Mercy would have learnt this too but unlike their brother’s later education, tradition saw to it that they learnt from their mother how to run a household when their time came. Educating local children in Cranbrook didn’t come about until 1518 when a ‘frescole for the poor children of Cranbrooke’ was founded by John Blubery, a yeoman in the king’s armoury. Some sixty years later, Cranbrook’s Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School was founded and where Walter Hendley, Walter’s nephew and namesake, and his cousins Richard Baker and Walter Roberts were three of the thirteen governors.

By 1517 Cranbrook was a prosperous town, it had seen its population rise boosted by immigrants wishing to make a living in the flourishing broadcloth industry, and by the beginning of the 16th century the Hendley’s were one of a number of important families, who we have seen in a previous chapter, lived in one of the grander houses in the village.

At this point in Walter’s childhood shiploads of wool, up to 30,000 tons at a time, were being brought into the area, this wool produced up to twelve thousand luxury woollen broadcloths a year that were destined to be shipped to such far off lands as Spain and the Mediterranean via the port of Rye. Dyes such as indigo and cochineal were also imported. If the Hendley children ever ventured into Cranbrook then they would have seen that it was a busy town full to the brim with businesses associated with the wool trade. By the mid 16th century Cranbrook had eight shopkeepers, shoemakers and carpenters and at least three barber surgeons, a milliner and a haberdasher. Although Walter’s father's main concern was the manufacture of broadcloth, he had strong business connections and his family were long associated with other families who had their foot in the door of the Tudor court. Gervais would, just like any other father in his position, use these connections to further not only his families fortunes but his son's career and with this in mind it is not beyond the realms of possibility Walter was educated away from home, because the path Walter found himself on was the study and application of the law. It is almost impossible to determine which person in Walter’s circle of family, friends and acquaintances placed him on the path of a career in local government and law, however, the most likely candidates are the Hales family from Tenterden or the Ashburnham family of Guesting in Sussex.

The Ashburnham's were a family of some note, their claim to their lands in Sussex can be dated to the time of the conquest of England, and in later centuries their money was made in the local iron industry. It is not beyond the realm of possibility that the initial introduction was made via Walter’s grandfather, the aforementioned Walter Roberts, who had a connection to the Ashburnham's as far back as 1492. Thomas Ashburnham was the second of three sons of Thomas Ashburnham, he held a number of prominent positions in Sussex and Surrey being Mayor of Winchelsea in 1508/9, Commissioner for Musters in 1511 and a Commissioner for Subsidy in 1515.

At this point in Walter’s childhood shiploads of wool, up to 30,000 tons at a time, were being brought into the area, this wool produced up to twelve thousand luxury woollen broadcloths a year that were destined to be shipped to such far off lands as Spain and the Mediterranean via the port of Rye. Dyes such as indigo and cochineal were also imported. If the Hendley children ever ventured into Cranbrook then they would have seen that it was a busy town full to the brim with businesses associated with the wool trade. By the mid 16th century Cranbrook had eight shopkeepers, shoemakers and carpenters and at least three barber surgeons, a milliner and a haberdasher. Although Walter’s father's main concern was the manufacture of broadcloth, he had strong business connections and his family were long associated with other families who had their foot in the door of the Tudor court. Gervais would, just like any other father in his position, use these connections to further not only his families fortunes but his son's career and with this in mind it is not beyond the realms of possibility Walter was educated away from home, because the path Walter found himself on was the study and application of the law. It is almost impossible to determine which person in Walter’s circle of family, friends and acquaintances placed him on the path of a career in local government and law, however, the most likely candidates are the Hales family from Tenterden or the Ashburnham family of Guesting in Sussex.

The Ashburnham's were a family of some note, their claim to their lands in Sussex can be dated to the time of the conquest of England, and in later centuries their money was made in the local iron industry. It is not beyond the realm of possibility that the initial introduction was made via Walter’s grandfather, the aforementioned Walter Roberts, who had a connection to the Ashburnham's as far back as 1492. Thomas Ashburnham was the second of three sons of Thomas Ashburnham, he held a number of prominent positions in Sussex and Surrey being Mayor of Winchelsea in 1508/9, Commissioner for Musters in 1511 and a Commissioner for Subsidy in 1515.

Whatever the connection, Walter Hendley arrived in the Ashburnham household as a young boy, how he applied himself to his new role goes unrecorded but it seems that he was efficient and conscientious enough to impress, and as he grew into a man it was Ashburnham, rather than his own father, who steered him towards a career in law. Thomas Ashburham’s motives are unclear but he had no son to follow in his footsteps and if he was an ambitious man, he may have looked to Walter to improve his own prospects. In 1483 Ashburnham had married Elizabeth Dudley, the sister of recently executed Edmund Dudley, but this made no difference to his own prospects, so if his family were to ever gain important positions in the administration of government and support and encouragement of one protégé wasn’t enough, a marriage however would - Walter was soon married to Ashburnham’s eldest daughter Ellen. Maybe Ashburnham wasn’t the only one planning a better future, Walter too may have seen his marriage as a step up the social ladder. Walter’s own family, as we have seen, were already associated with Kentish nobility, but by marrying Ellen, Walter became the uncle, albeit by marriage of the nineteen year old John Dudley, (later Duke of Northumberland) The Hendley's were not flying as high as their Guildford and Dudley associates, however, in later years this would prove to be an advantage! In a few years the Guildford's would cease to be, and the Dudley’s would get their wings clipped. In the meantime, Walter would be content to learn the ways of local government from his father in law.

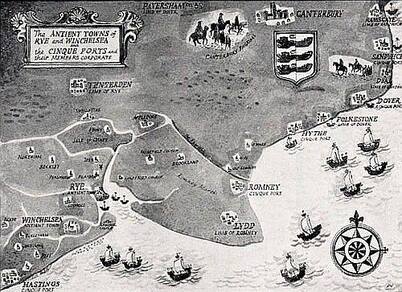

Prior to the 15th century, England had no permanent navy to defend itself from foreign enemies. Instead, five ports in the South East of the country were contracted by the Crown to provide a defensive fleet when required. One of these ports was Winchelsea; it had been added, along with Rye, to the main ports of Hastings, Sandwich, Dover, Romney and Hythe. These seven ports came under the collective name of Cinque Ports. Thomas Ashburnham held a number of posts at Winchelsea and Rye, and Edward Guildford would take up the position as Warden in 1521. It is highly likely that the Hendley’s association with either one of these men secured him his first post as counsel to the said cinque ports, So, Walter had a new wife, a new home and a promising career, it would seem that he had it all, and this was the case for the first few years of his marriage, but in 1523 tragedy struck.

Walter and Ellen were married by 1518, but where they began their married life is not known, with Walter’s parents still occupying the house on their manor of Coursehorn, it seems sensible that they lived at Guestling, the manor that Thomas Ashburnham had inherited from his own father. Elizabeth soon became pregnant and by 1519 she had given birth to their first child, a daughter they named Elizabeth, probably named after both her grandmothers. Ellen soon followed and finally Anne was born in 1523. The exact date of her birth is not known, however by the end of the year Walters' wife was dead. Her father had returned from London, a place he said was ‘detrimental to his health.’ Whatever he brought back with him to Guestling may have cost him, his wife and their daughter their lives.

Guestling was a quiet rural area, a parish made up of three hamlets with few buildings, the streets of Tudor London however, where Thomas Ashburham went about his business, was filled with lines of tall buildings. It was a dark and dismal place where the streets were covered in mud that are said to have given off a vile odour. This mud was continually being walked into peoples homes. The Tudor philosopher and humanist Erasmus noticed the practice of the spreading fresh rushes on the floors of houses, he also noted that all but the very top layer was almost never changed, he wrote ‘so as to leave a basic layer, sometimes for twenty years, under which fester spittle, vomit, dog’s urine and men tto, dregs of beer and cast off bits of fish, and other unspeakable kinds of filth’ - a breeding ground for all manor of diseases! Sweating sickness had been and gone, in 1519 Malaria had made an appearance, however there was a recorded outbreak of the plague in 1523. Early that year Thomas Ashburham returned home to Guesting along with his friend and neighbour Edmund Franke, by the May of that year plague had carried off Franke, so we can be fairly positive that Thomas Asburnham had contracted it, for his death is recorded as 1523 as well. There is no mention of his wife Elizabeth either, she may have predeceased him or the plague took her too.

Walter and Ellen were married by 1518, but where they began their married life is not known, with Walter’s parents still occupying the house on their manor of Coursehorn, it seems sensible that they lived at Guestling, the manor that Thomas Ashburnham had inherited from his own father. Elizabeth soon became pregnant and by 1519 she had given birth to their first child, a daughter they named Elizabeth, probably named after both her grandmothers. Ellen soon followed and finally Anne was born in 1523. The exact date of her birth is not known, however by the end of the year Walters' wife was dead. Her father had returned from London, a place he said was ‘detrimental to his health.’ Whatever he brought back with him to Guestling may have cost him, his wife and their daughter their lives.

Guestling was a quiet rural area, a parish made up of three hamlets with few buildings, the streets of Tudor London however, where Thomas Ashburham went about his business, was filled with lines of tall buildings. It was a dark and dismal place where the streets were covered in mud that are said to have given off a vile odour. This mud was continually being walked into peoples homes. The Tudor philosopher and humanist Erasmus noticed the practice of the spreading fresh rushes on the floors of houses, he also noted that all but the very top layer was almost never changed, he wrote ‘so as to leave a basic layer, sometimes for twenty years, under which fester spittle, vomit, dog’s urine and men tto, dregs of beer and cast off bits of fish, and other unspeakable kinds of filth’ - a breeding ground for all manor of diseases! Sweating sickness had been and gone, in 1519 Malaria had made an appearance, however there was a recorded outbreak of the plague in 1523. Early that year Thomas Ashburham returned home to Guesting along with his friend and neighbour Edmund Franke, by the May of that year plague had carried off Franke, so we can be fairly positive that Thomas Asburnham had contracted it, for his death is recorded as 1523 as well. There is no mention of his wife Elizabeth either, she may have predeceased him or the plague took her too.

If Walters family were living with the Ashburnham's at Guestling it is quite possible that any one of them could have contracted the plague. Elizabeth was especially vulnerable due to the fact she had just giving birth to her daughter Anne. You can imagine what was going through her mind as she held her baby arms. Elizabeth wouldn’t know that breast feeding the baby herself might protect her her from harm, but women of rank in this period did not breastfeed they used the services of a wet nurse, for they considered this to be important to the survival of a newly born baby. Tudor women like Elizabeth Hendley believed that the person the child became was down to the breast milk it received, they thought it contained everything that would shape the child's life, and that included its character. It was not only vital therefore that she chose a wet nurse who was of good health but she had to be of good moral character as well. Sadly, within days Elizabeth did become ill and was soon dead.

However, neither Walter nor his children became infected, so it would seem that Elisabeth might have died following complications of childbirth, either way by the Christmas festivities of 1523 Walter Hendley was a twenty-four year old widower with two small children and a new-born baby. Following his wife’s death, the immediate problem for Walter was who would care for Elizabeth, Ellen and Anne, the most obvious answer would be a member of his own family at Coursehorn. As mentioned his parents were still alive and he had three married sisters, but who did raise Walter’s young daughters is unknown, also unknown is how he coped emotionally with his loss, but cope he did.

Walter was a young man and his thoughts would soon turn to matrimony, he was not the only one, Henry VIII was also looking for a new wife. Henry’s choice would be Anne, the daughter of the Boleyn family of Blickling Hall in Norfolk. Walter’s new wife was of the Pigott family of Whaddon in Buckinghamshire.

However, neither Walter nor his children became infected, so it would seem that Elisabeth might have died following complications of childbirth, either way by the Christmas festivities of 1523 Walter Hendley was a twenty-four year old widower with two small children and a new-born baby. Following his wife’s death, the immediate problem for Walter was who would care for Elizabeth, Ellen and Anne, the most obvious answer would be a member of his own family at Coursehorn. As mentioned his parents were still alive and he had three married sisters, but who did raise Walter’s young daughters is unknown, also unknown is how he coped emotionally with his loss, but cope he did.

Walter was a young man and his thoughts would soon turn to matrimony, he was not the only one, Henry VIII was also looking for a new wife. Henry’s choice would be Anne, the daughter of the Boleyn family of Blickling Hall in Norfolk. Walter’s new wife was of the Pigott family of Whaddon in Buckinghamshire.

All but one of Walter's maternal ancestors had selected their wives from local families, the Pigott's however originate from the county of Buckinghamshire. Margery's family home at Whaddon was just under a hundred miles from Walter’s home in Sussex, this suggests a connection via his associates within the law. Historically, the Pigott’s Buckinghamshire holdings of Whaddon, Little and Great Horwood and Lillingstone Dayrell were held by Walter Giffard, who fought at Hasting and whose son, also Walter, was the first Earl of Buckingham. By the later half of the 15th century these manors were held by Margery’s ancestors.

Margery was Thomas and Elizabeth Pigott’s only daughter, she had married Thomas Cotton of Landswade in Cambridgeshire, but that marriage was short lived and she was a widow at the age of nineteen, however, within two years she had married Walter, their marriage taking place in the July of 1527. Walter and Margery were a similar age, and no doubt Walter would be looking forward to the birth of a son. There is no reference to a child from her marriage to Thomas Cotton and in the twenty three years she was married to Walter she never bore him any children. The lack of offspring could have serious repercussions in families, and the lack of a male heir was proving a problem for Henry VIII, and this cost his wives dear. It would have been obvious to Margery that the problem lay with her, maybe she was aware of the writings of the day on this subject, medical treaties and recipes included advice to help a woman conceive and a man beget a child, but sadly a child never arrived. Walter must have resigned himself to not having a son and Margery took on the task of caring for Walter’s daughters, Elizabeth who was now eight, Ellen six and Anne aged four. In 1550 Walter wrote in his Will ‘I charge vppon my blessynge euery of my doughters Elisabeth, Eleyne and Anne to be lovynge to my sayd wyf for the same Dame Margery my wyfe hath been vnto all my sayd doughters syns the tyme of our maryage more lyke a naturall mother then a mother in lawe (step mother) so we have to assume that she did. There is no evidence to suggest she turned out to be the archetypal wicked step mother.

Margery was Thomas and Elizabeth Pigott’s only daughter, she had married Thomas Cotton of Landswade in Cambridgeshire, but that marriage was short lived and she was a widow at the age of nineteen, however, within two years she had married Walter, their marriage taking place in the July of 1527. Walter and Margery were a similar age, and no doubt Walter would be looking forward to the birth of a son. There is no reference to a child from her marriage to Thomas Cotton and in the twenty three years she was married to Walter she never bore him any children. The lack of offspring could have serious repercussions in families, and the lack of a male heir was proving a problem for Henry VIII, and this cost his wives dear. It would have been obvious to Margery that the problem lay with her, maybe she was aware of the writings of the day on this subject, medical treaties and recipes included advice to help a woman conceive and a man beget a child, but sadly a child never arrived. Walter must have resigned himself to not having a son and Margery took on the task of caring for Walter’s daughters, Elizabeth who was now eight, Ellen six and Anne aged four. In 1550 Walter wrote in his Will ‘I charge vppon my blessynge euery of my doughters Elisabeth, Eleyne and Anne to be lovynge to my sayd wyf for the same Dame Margery my wyfe hath been vnto all my sayd doughters syns the tyme of our maryage more lyke a naturall mother then a mother in lawe (step mother) so we have to assume that she did. There is no evidence to suggest she turned out to be the archetypal wicked step mother.

The year before his marriage to Margery, Walter was still employed as counsel to the Cinque Ports. The Rye Chamberlin accounts for 1526 show that he was paid an annual fee of 13s 4d (which is the equivalent of nearly £300 in today's money) by the Brotherhood of the Cinque Ports and at the same time he was acting as prosecuting council representing the town of Sandwich in a lawsuit. In 1530, and again in 1535, Walter was a Lent Reader in the London law court of Gray's Inn. A reader, of which there were two annually, was originally a senior barrister chosen to deliver a course of lectures on legal matters, either to the Inner Temple or one of its Inns of Chancery. It was the usual practice that a reader be nominated for this role and it is likely that Walter owes his recommendation to either Christopher or John Hales who had been readers in previous years. Walter’s kinsman, Sir John Baker, a Cranbrook lawyer, who at this time was attorney general for the Duchy of Lancaster, is another candidate for Walters appointment, but whoever it was his name goes unrecorded.

In 1532, Gervais Walter’s father died, and his will dated the 15th April 1532 makes interesting reading, it was just concerned with the dispersal of his goods and chattels. Walter received

‘flatt hoope of golde, my best salts parcell gilte with oon cover, 6 of my best spones wt Angells…. fetherbed the bolsters of fethers being at Richard Taylours and the fetherbed wt out a bolster that is at my howse in the towne, twoo carpet cusshens, the hangings, selers and Testars, bedstedylls, Tubbys bulting whoche and Kneding Trouwgh and all other bords and planks being at my said house in the towne.’

This town house had been the home of his grandfather Thomas Hendley. There was no mention of the distribution of his land or property although three pecks of land in Cranbrook and 9 acres of land on his manor of Coursehorn were bequeathed to Thomas Hendley, Walter’s brother. Gervase’s Will wasn’t finalised until over a year later, it seems he was thinking long and hard about who should get what.The ancient inheritance system of Gavelkind was in operation here, this law gave each son an equal share of his father's land and property depending on the testator's wish, this was different from the usual law of primogeniture where only the eldest son received it all. By November of 1533, the Will was settled and Walter was to receive all his father’s lands including the manor of Coursehone, except for the manor of Tenderten and Benenden which went to his brothers William and Thomas respectively. Interestingly, the lands listed above in the 1532 Will later transferred from Thomas to Walter. Walter was now head of the family and the new owner of the Hendley manor of Coursehorne. As previously mentioned this manor was triangular in shape and was bordered on its western side by Cranbrook. To its north, south and eastern side were the manors of Sissinghurst, Beneden and Golford respectively and it probably measured no more than half a mile in each direction. The main buildings on the manor where the aforementioned manor house, a weavers cottage, and a cloth hall and at some point during the Tudor period this cloth hall became a home, new flooring was added, as was wood panelling, stone fireplaces and windows. It is not beyond the realms of possibility that these alterations were made soon after Walter’s marriage to Margery as a home for her to raise Walter's daughters.

In 1532, Gervais Walter’s father died, and his will dated the 15th April 1532 makes interesting reading, it was just concerned with the dispersal of his goods and chattels. Walter received

‘flatt hoope of golde, my best salts parcell gilte with oon cover, 6 of my best spones wt Angells…. fetherbed the bolsters of fethers being at Richard Taylours and the fetherbed wt out a bolster that is at my howse in the towne, twoo carpet cusshens, the hangings, selers and Testars, bedstedylls, Tubbys bulting whoche and Kneding Trouwgh and all other bords and planks being at my said house in the towne.’

This town house had been the home of his grandfather Thomas Hendley. There was no mention of the distribution of his land or property although three pecks of land in Cranbrook and 9 acres of land on his manor of Coursehorn were bequeathed to Thomas Hendley, Walter’s brother. Gervase’s Will wasn’t finalised until over a year later, it seems he was thinking long and hard about who should get what.The ancient inheritance system of Gavelkind was in operation here, this law gave each son an equal share of his father's land and property depending on the testator's wish, this was different from the usual law of primogeniture where only the eldest son received it all. By November of 1533, the Will was settled and Walter was to receive all his father’s lands including the manor of Coursehone, except for the manor of Tenderten and Benenden which went to his brothers William and Thomas respectively. Interestingly, the lands listed above in the 1532 Will later transferred from Thomas to Walter. Walter was now head of the family and the new owner of the Hendley manor of Coursehorne. As previously mentioned this manor was triangular in shape and was bordered on its western side by Cranbrook. To its north, south and eastern side were the manors of Sissinghurst, Beneden and Golford respectively and it probably measured no more than half a mile in each direction. The main buildings on the manor where the aforementioned manor house, a weavers cottage, and a cloth hall and at some point during the Tudor period this cloth hall became a home, new flooring was added, as was wood panelling, stone fireplaces and windows. It is not beyond the realms of possibility that these alterations were made soon after Walter’s marriage to Margery as a home for her to raise Walter's daughters.

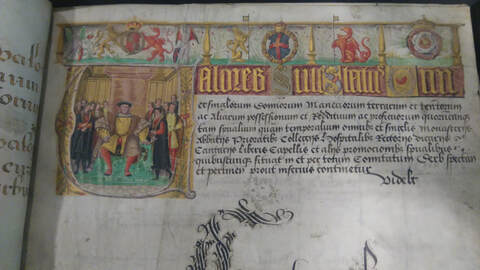

In 1535 when Walter was still at Gray’s Inn, Thomas Cromwell had introduced the ‘Valor Ecclesiasticus’ - a survey to find out just how much property was owned by the church and the following year he established the Court of Augmentations, the workings of which was modelled on the aforementioned Duchy of Lancaster. This court was set up as part of the Dissolution of the Monasteries to administer monastic properties and revenues that had been confiscated from the crown and Walter soon found himself working as a lawyer in the rooms of Robert Southwell, one time tutor of Cromwell’s son Gregory. In this position Walter would have been aware of what was happening in the royal court at the time. No sooner had Walter sat at his desk than news was circulating of the kings fall from his horse, the queen’s miscarriage and the arrival of a new royal mistress, accusations of adultery and Anne Boleyn's execution - Walter Hendley had been in his new job five months!

Two years after the Court of Augmentations was established, Cromwell was continuing his campaign against the old religion, he would see to it that its statues, rood screens and religious images were all destroyed, and this culminated in September of 1538 with the dismantling of the shrine of Thomas Becket at Canterbury. The following November, and into the January of 1539 Walter can be found actively pursuing Cromwell’s campaign in the north of the country and it was Walter, who in 1541 oversaw the final dissolution of Canterbury’s cathedral along with that of Christchurch and Rochester. It is easy to think that the men who carried out Cromwell’s orders had no social conscience, that they cared nothing for those who lost everything, but in Walter’s case I do think that he may have felt some sense of guilt for the sacrilege he performed against Canterbury, and I wonder was this why he was instrumental in securing the passage of an Act of Parliament which reaffirmed the Canterbury Cathedral’s privileges a few years later. After Cromwell’s execution is 1541, the Court of Augmentations were amalgamated with the Court of General Surveyors and those working within it were soon looking for other posts. The aforementioned Robert Southwell became a member of the King’s ‘Ordinary Council’ and later as one of the Masters of Requests. Walter ended up in benevolences, a position which saw him travelling around the country extracting loans from the wealthy in order to pay for expenses accrued by the crown. Walter worked on numerous royal commissions, was the member of parliament for Canterbury and in 1546 was briefly considered for Chancellor of Ireland, but the post went to Sir Thomas Cusack. By now Walter Hendley was a wealthy man, much of his money was made from his time in augmentations. He acquired eleven pieces of confiscated monastic lands in Kent and purchased a number of manors including one from poet Sir Thomas Wyatt, he also had the lease of a property in the manor of Holborn for which he paid a yearly rent of a red rose. Walter then, was not averse to benefiting from the fall of others or taking advantage of the opportunities afforded him, he wouldn’t be the first or the last to do that. Walter Hendley had a successful career in local government and law for nearly thirty-years despite being associated with those who conspired to make changes. It is easy to see with hindsight why Walter might have kept his head down when all around were losing theirs, but that was history in the making, nobody knew what fate had in store.

Over the next few years Walter Hendley continued to work primarily in law, and in 1546, and as mentioned was the member of parliament for Canterbury. That same year, as part of the descent of the Howards and the rise of the Seymours, Walter was one of the five royal officials who put his signature to a document enabling the exchange of lands between his nephew in law the Duke of Northumberland and Henry VIII. This would be the last instance of Walter acting for the crown under Henry VIII - by the January of 1547 the king was dead. Henry’s successor was his nine year old son of Edward, in his Will Henry named sixteen executors who were to act as Edward's council until he reached the age of eighteen. One of the sixteen was Northumberland. Within months of the new king's accession to the throne, Walter was knighted, this was unusual as typically only nobility received a knighthood. How this came about is not known, but it is likely Dudley put Walter’s name forward, hedging his bets you might say, a good move if you have ideas above your station as the John Dudley most definitely had. Within three months of Henry’s death these executors merged to become the young king’s council. Edward Seymour was named Lord Protector and initially he would have the support of Northumberland, but within two years, following Kett’s Rebellion, the infighting began. Walter Hendley had never been a main player, he was a government official at the beck and call of people like Thomas Cromwell and John Dudley, but history shows us that it was men like Walter who often got caught up in their designs and conspiracies and were dragged down too. Maybe this was the reason Walter left London, but more than likely he was just too old and too tired. When Walter had returned home to Coursehorn he was nearly blind, despite problems with his sight he continued to work in a local administrative role, but as his eyesight deteriorated so did his health.

Being at home at Coursehorn, Walter would have had the time to spend with his wife in their splendid Tudor home and consider how lucky he was that Margery had cared for his daughters in all those years he spent in the city. Walter’s daughter's childhood had most likely spent in the company of their stepmother and there is nothing to suggest that their younger years were anything other than happy, and the romantic in me likes to think that both Walter and Margery wished this to continue into their married lives. Walter would have thought long and hard about finding husbands for these girls, and during his time in the city he must have crossed paths with men who might make a suitable husband. However, Walter may have been witness to the heads of two queens dropping onto the scaffold, or heard stories of the ruin of women who had married into the families of those who frequented Henry VIII’s world. Walter considered it better to look closer to home.

All three of Walter Hendley’s daughters were married into families that the Hendley’s had known for years. Elizabeth had married William Waller, the son of John Waller of Groombridge, a manor in Sussex that had been in the Waller family from the mid 14th century. Ellen, Walter’s second daughter, had married Thomas Culpeper, the eldest son of Alexander and his wife Constance Chamberlyn. The 15th century Culpeper’s being a rebellious lot were associated with other like minded Kentish families and if they were not rebelling against Richard III they were running roughshod around the country abducting women and imprisoning them in their manor houses. Local plots and acts of violence seem to crop up frequently in this family's history. Anne, Walter’s youngest daughter, was just a tiny baby when her mother died in 1523, she had married Richard Covert. The Covert’s origins can be traced to the Sussex village of Sullington to the 13th century. By the end of the 15th century William Covert, Richard’s great grandfather had purchased the manor of Slaugham and this estate would be the family’s main residence for the next two centuries. Walter’s grandchildren and great grandchildren would go on to gain prominent roles during the Reformation, the Elizabethan era and the English Civil War. Sadly, however, Walter would only live long enough to see the first of his grandchildren pass from childhood into adulthood.

All three of Walter Hendley’s daughters were married into families that the Hendley’s had known for years. Elizabeth had married William Waller, the son of John Waller of Groombridge, a manor in Sussex that had been in the Waller family from the mid 14th century. Ellen, Walter’s second daughter, had married Thomas Culpeper, the eldest son of Alexander and his wife Constance Chamberlyn. The 15th century Culpeper’s being a rebellious lot were associated with other like minded Kentish families and if they were not rebelling against Richard III they were running roughshod around the country abducting women and imprisoning them in their manor houses. Local plots and acts of violence seem to crop up frequently in this family's history. Anne, Walter’s youngest daughter, was just a tiny baby when her mother died in 1523, she had married Richard Covert. The Covert’s origins can be traced to the Sussex village of Sullington to the 13th century. By the end of the 15th century William Covert, Richard’s great grandfather had purchased the manor of Slaugham and this estate would be the family’s main residence for the next two centuries. Walter’s grandchildren and great grandchildren would go on to gain prominent roles during the Reformation, the Elizabethan era and the English Civil War. Sadly, however, Walter would only live long enough to see the first of his grandchildren pass from childhood into adulthood.

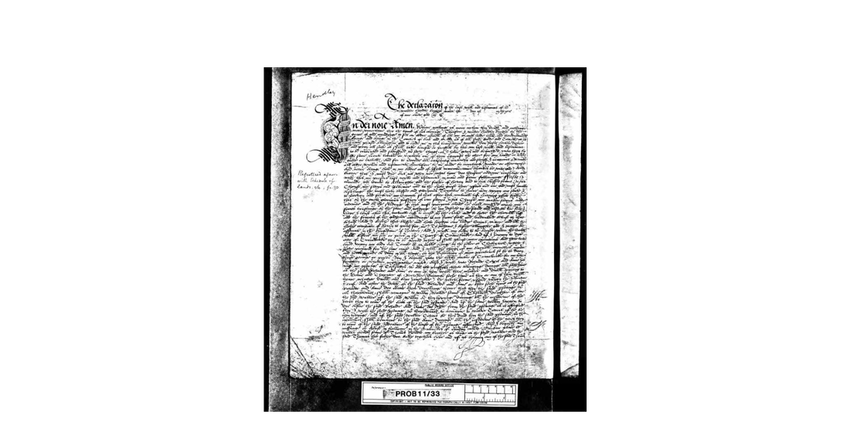

By the spring of 1550 Walter Hendley was ailing, and by the end of April his wife was worried enough by his condition that she called for a doctor. Johannes Howell ‘medicinis professor’ duly arrived and confirmed that Walter was sick and likely to die. In the house at the same time was Thomas Roberts, Walter’s first wife's step brother, Thomas asked Howells how long Walter had left and Howells told him he did not have long. Walter Hendley died four hours later, he was just fifty-six. In the days following Walter’s death it became apparent that his will could not be found despite the fact a number of people knew of its existence. With no will Walter would be deemed as having died intestate, as soon as this fact was known claimants would be hovering like vultures around a carcass. The absence of this will soon caused a problem, the exact reason is not known, but might have something to do with the distribution of the estate of Walter’s father on his death in 1532 where initially land in Coursehorn was left to Walter’s brothers, but suddenly left to Walter. Maybe one or both of the brothers were attempting to claim back what they considered rightfully theirs? The case of the missing will ended up in the law courts, and records show that nine people gave a deposition, we only know what four of them had to say.

Firstly Margery, Walter's wife, stated that she knew that he had ‘set all in order.’ George Prior, Walter’s clerk and chaplain said that he had heard him say that he’d made his last will and testament. The aforementioned Thomas Roberts stated that he saw a will and it was in Walter's own handwriting, and Johannes Howell stated that he being in the house of Sir Walter Hendley in Cranebrook perceiving him to be sick and like to die persuaded him to make his will and that Walter answered ‘Man I fele no suche thing in myself whereby I should so doo, as touching my landes I have executed of it.’

Firstly Margery, Walter's wife, stated that she knew that he had ‘set all in order.’ George Prior, Walter’s clerk and chaplain said that he had heard him say that he’d made his last will and testament. The aforementioned Thomas Roberts stated that he saw a will and it was in Walter's own handwriting, and Johannes Howell stated that he being in the house of Sir Walter Hendley in Cranebrook perceiving him to be sick and like to die persuaded him to make his will and that Walter answered ‘Man I fele no suche thing in myself whereby I should so doo, as touching my landes I have executed of it.’

The outcome of this legal action is lost to history but strangely the will turned up, it was dated the 22nd April 1550 and a grant of probate had be granted some for days later? Even later still a list is attached documenting all of Walter’s lands, his tenants and the rent payable and to whom the rent should be paid. Walter's Will was registered again and a grant of probate for this is dated in the March of 1551. With the will officially accounted for Walters estate was finally settled according to his wishes. it begins ‘First i bequeath my soule to God, Our Ladye and all the Company of Heaven. My body to be betrayed under the south wall before my sete or pewe in the Church of Cranebroke, and if I happen to dye oute of Cranbroke the to be betrayed where it please myn executors and there shall he keyed upon my body one tomb of marble lyenge if the seller at Clerkenwell which I have prepared for the same cause. To the high alter of Cranebroke 40s’ Walter leaves 20s to eight churches where the ‘curate of every of said churches shall pray for my soule and bestow in every of the said churches to the priest and clerks 6s 8d and 6s 8d to the hones men of the parish to make merry and 6s 8d to the poor people...’ Walter left bequests for his servants, clerks for ‘my hertye thanks for the paynes they have taken with me’ but the bulk of his lands were divided between his three daughters. The two daughters of John Ashburnham, his first wife’s cousin, were also remember, his son in laws Thomas Culpepper, Richard Covert and George Fane were left £40 each. Margery too was well provided for.

Interestingly, as with his father’s Will there is no mention of his manor of Coursehorne, the lands of which had been in the family since before the conquest, Walter makes no mention, but it does appear at the very end of the aforementioned list as being left to his brother Thomas Hendley. In later years the manor or Coursehorn can later be found as part of the estate of Thomas’s son Walter and generations later it can be found descending through the family until the end of the 18th century when the last male heir died a lunatic.

Walter Hendly had spent his childhood in the hunting ground of those men who had a hand in bringing down the Plantagenet dynasty; he was well acquainted with those same families who climbed the ladder of success under Henry VII. In his later life he had witnessed the downfall of two of Henry’s queens, and played his part in Cromwell's suppression of the monasteries. Maybe Walter could have climbed higher up the social ladder, but I think he preferred to be on the peripheries, I also like to think that Walter did not lack ambition, but rather understood the price of too much. You could compare Walter’s early life to that of Thomas Cromwell, both were sons of minor gentry and both had the opportunity to better themselves, but the comparison really ends there. Walter Hendley may have been ambitious, but not ambitious enough, Cromwell had ambition a plenty and was a risk taker whereas Walter was most certainly not. This meant of course, that Walter died a wealthy man in his own bed while Cromwell’s life ended tragically. Walter then, was a man who had seen everything but had been wise to keep his distance, he was a family man at heart, and from his will we can see that that was important to him.

Interestingly, as with his father’s Will there is no mention of his manor of Coursehorne, the lands of which had been in the family since before the conquest, Walter makes no mention, but it does appear at the very end of the aforementioned list as being left to his brother Thomas Hendley. In later years the manor or Coursehorn can later be found as part of the estate of Thomas’s son Walter and generations later it can be found descending through the family until the end of the 18th century when the last male heir died a lunatic.

Walter Hendly had spent his childhood in the hunting ground of those men who had a hand in bringing down the Plantagenet dynasty; he was well acquainted with those same families who climbed the ladder of success under Henry VII. In his later life he had witnessed the downfall of two of Henry’s queens, and played his part in Cromwell's suppression of the monasteries. Maybe Walter could have climbed higher up the social ladder, but I think he preferred to be on the peripheries, I also like to think that Walter did not lack ambition, but rather understood the price of too much. You could compare Walter’s early life to that of Thomas Cromwell, both were sons of minor gentry and both had the opportunity to better themselves, but the comparison really ends there. Walter Hendley may have been ambitious, but not ambitious enough, Cromwell had ambition a plenty and was a risk taker whereas Walter was most certainly not. This meant of course, that Walter died a wealthy man in his own bed while Cromwell’s life ended tragically. Walter then, was a man who had seen everything but had been wise to keep his distance, he was a family man at heart, and from his will we can see that that was important to him.

Walter was laid to rest somewhere along the south wall of St Dunstan’s Church where there is no memorial to him or his family, in death as in life, Walter Hendley preferred to be out of the limelight.

Walter’s death left his wife a widow for the second time. Within three years she had married Thomas Roberts, Walter’s first wife’s nephew, Margery would outlive him too, Thomas died in 1576. There were no children born of this marriage.

Walter’s death left his wife a widow for the second time. Within three years she had married Thomas Roberts, Walter’s first wife’s nephew, Margery would outlive him too, Thomas died in 1576. There were no children born of this marriage.