An Introduction

I would like to dedicate this family history to my dear Uncle Keith Purches who passed away during the writing of the Purches's story. He was a true Cornishman

On the second day of August 1100, a man by the name of Purkis, a charcoal burner by trade, was traveling through the New Forest in Hampshire when he came upon a man lying on the woodland path in front of him. Purkis soon realised that this was no ordinary man, in fact, it was England’s king, dead with an arrow embedded in his chest. The area in which the king lay was flattened, and there was blood seeping into the soil but there was nobody to be seen, however, there was evidence that whoever was with the king had left quickly leaving broken twigs and branches pointing in the direction that they fled. Purkis lifted the body of William Rufus, the third son of William the Conqueror, placed him in his cart, and headed for Winchester. The charcoal burner returned to the forest and obscurity with, one hopes, a reward for his trouble.

Above is the story of Purkis, who if my grandfather is to be believed, was one of our ancestors. It was a tale he told me many years ago, but it is also a tale told by many interested in the history of kings and a tale that has been repeated since the mid-18th century when it morphed from fiction to fact, evidence of which can be found engraved on the Rufus Stone, a memorial to this event, in the New Forest.

It is highly unlikely that Purkis was a member of my family, but my Purches roots are, however, embedded in the chalky soil of Hampshire. Their names first appear in documents at the beginning of the 18th century in Portsea, a small village surrounded by farmland just a few miles north east of Portsmouth and Henry VIII’s famous dockyard.

In 1707, some ten years before the birth of the first Purches in Portsea, the Act of Union was passed by the English and Scottish Parliaments, this led to the creation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and this, in turn, led to the development of British identity. We can see this clearly in our success at sea and how, from the Napoleonic Wars, right through to the Falklands War, the Royal Navy shaped the character and the identity of the British nation. This identity was celebrated in 1740 with the anthem Rule Britannia, the chorus of which states ‘Britannia rules the waves’ from then on the Royal Navy was seen as the world's most powerful sea force until the Second World War.

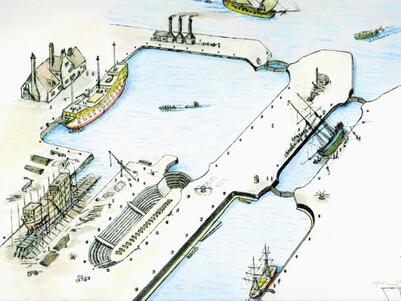

Portsea is the area immediately around the Royal Naval Dockyard, and it was here that the Romans, the earliest visitors to our country, discovered the natural shelter offered by Portsmouth harbour, they built a fort at Porchester, which would later become Portchester Castle. Years later, in 1180, a wealthy Norman merchant, Jean de Gisor, founded Portsmouth when he purchased the manor of Buckland; he soon found that Portsmouth harbour provided a safe haven for his merchant ships and was an ideal location to trade with Normandy. There has been a naval dock at Portsmouth since 1194, but it was Henry VII who built the world's earliest known dry dock here, and it was during the Tudor period that the dockyard saw a dramatic expansion beginning with the Round Tower, the Square Tower and Southsea Castle, all built to provide protection from invasion.

To quote from Bartholomew’s Gazetteer of the British Isles Portsmouth is - ‘ naval station, seaport, and part of Portsea Island, Hampshire opposite the Isle of Wight. Eighteen miles south-east of Southampton and seventy-four south-west of London’ It is ‘divided into the four districts of Portsmouth, Portsea, Landport and Southsea. Portsmouth being the barracks and garrison town, Portsea the sweat of the greatest naval dockyard, Landport the artisan’s quarter and Southsea a modern watering-place with fine esplanade and pier, baths and assembly rooms.’

To quote from Bartholomew’s Gazetteer of the British Isles Portsmouth is - ‘ naval station, seaport, and part of Portsea Island, Hampshire opposite the Isle of Wight. Eighteen miles south-east of Southampton and seventy-four south-west of London’ It is ‘divided into the four districts of Portsmouth, Portsea, Landport and Southsea. Portsmouth being the barracks and garrison town, Portsea the sweat of the greatest naval dockyard, Landport the artisan’s quarter and Southsea a modern watering-place with fine esplanade and pier, baths and assembly rooms.’

Ruling the country in 1733, the time of the birth of Samuel Purches, was George II and governing was Prime Minister Thomas Pelham-Hollis. Great Britain, on the surface at least, was a county of refinement, culture and of fine living. We see this reflected in the artworks of Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds, through the words of William Wordsworth and John Keats, but it was also defined by squalor, violence, and drunkenness and this too can be viewed in the works of satirical cartoonists James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson and William Hogarth.

To find the ancient origins of the family of Purches, despite it being an unusual name, is an impossible task, however, there is an explanation of the origins of the name. According to the Oxford Reference of Family Surnames in Great Britain and Ireland the most common spelling of Purches, was Purchase an Anglo-Norman word meaning ‘to acquire’ no surprise there then. Later, when Middle English was being spoken the word Purchas was used to mean a mercenary - signifying one who fights to take something from someone else. The earliest reference to the name in documents is during the reign of Richard II, when one William Purchaz can be found in the Essex Pipe Roll. Poor old Purkis the Charcoal Burner whose name predates said Purchaz by ninety years doesn't even get a mention.

With their family established in Portsea by the mid-18th century, it will not come as a surprise that the Purches’s were a seafaring family, many were sailors, and those who were not were involved with shipbuilding and other occupations related to the sea. The women of earlier generations were often left alone for years at a time while their husbands sailed the oceans to foreign lands, evidence of this is plain to see in the timing of the conception of the next generation, a generation who would leave these southern shores to head north to Norfolk and then south-west to Cornwall.