Scoboryo 1640 - 1686

A Time of Civil War

Fifteen years before the marriage of the first of the Scoboryo in St Columb Major, Charles I was crowned king of England at Westminster Abbey, after which he spent most of his time in a power struggle with Parliament. By 1629 Charles had had numerous arguments with his ministers which lead him to abolish Parliament. Charles could do this under what was known as Royal Prerogative, the divine right to rule, but by the middle of the century he was wading into trouble, many people regarding him as insensitive. Charles’s implementation of his prerogative covered the years between 1629 to 1640, eleven years of what you could claim was a semblance of peace. Equally, it could be argued that it was really eleven years of tyranny. It was during these years that the descendants of the Skyburriowe family arrived in St Columb Major in Cornwall.

Most of the population of England were outraged by the king’s non-parliamentary use of the law to raise money, most notorious was Ship Money a medieval law that was enacted when there were fears of an invasion. Under this law monarchs were able to order coastal towns to provide ships or the money to build vessels, however, Charles extended this levy to include inland counties as well, stating that

"the charge of defence which concerneth all men ought to be supported by all"

Unfortunately for Charles not all would support this tax, west country MP Richard Strode was one, as was John Hampden. Hampden was MP for Buckinghamshire in both the Short and Long Parliament, he would fight a high profile court case against this tax, he would go on to be one of the five members, three of which hailed from West Country, who the king attempted to arrest in the House of Commons in 1642. When the king forced the country to pay for his maritime and military catastrophes he would find that Cornwall was pretty hostile to this way of raising money. Charles’s most western county was forced to pay over £2,000 in tax and it was reported that

“gentlemen of most sufficiency were not able to give in that manner.”

"the charge of defence which concerneth all men ought to be supported by all"

Unfortunately for Charles not all would support this tax, west country MP Richard Strode was one, as was John Hampden. Hampden was MP for Buckinghamshire in both the Short and Long Parliament, he would fight a high profile court case against this tax, he would go on to be one of the five members, three of which hailed from West Country, who the king attempted to arrest in the House of Commons in 1642. When the king forced the country to pay for his maritime and military catastrophes he would find that Cornwall was pretty hostile to this way of raising money. Charles’s most western county was forced to pay over £2,000 in tax and it was reported that

“gentlemen of most sufficiency were not able to give in that manner.”

Other issues dominated parliament too, but it would be religion that would prove to be the most divisive issue that both Charles and Parliament would have to deal with. The Cornish could still remember raising their voices in unison in the name of religious change, and now it was those close to government and loyal to the crown who were shouting the loudest. Thomas Wentworth (whose execution Charles would later sanction) and Archbishop Laud were seen as the embodiment of all that was wrong with England at the time. Thomas Wentworth would be executed in 1641, Laud in 1645 and Hampden would die from his wounds at the Battle of Chalgrove Field in 1643.

Today, we may find the ideas of Divine Right ludicrous and somewhat amusing, but what must be remembered is the cost of it to our ancestors.

In Cornwall, there were those with links to the Scoboryo’s who were loyal to the crown such as Sir Bevil Grenville, Sir John Arundell of Trerice, Sir Richard Vyvyan and Sir Francis Godolphin, those who took up arms for the Parliamentarians were John St Aubyn and Richard Erisy, the fates of these Cornish men lay in the outcome of the wars. Out of these five men, the two Parliamentarians were generously rewarded, two of those who supported Charles were fined and lost (for a time) their estates. Only Sir Bevil Grenville lost his life.

We know that the civil wars put family against family and father against son and no better example of this is William Frederick Yeames's painting where a little boy in a royalist household is being spoken to by parliamentarians who ask the question "And When Did You Last See Your Father" which quite naturally puts the child in a difficult position and his family in a dangerous one.

These wars certainly placed friend against friend as the aforementioned Sir Bevil Grenville found.

Today, we may find the ideas of Divine Right ludicrous and somewhat amusing, but what must be remembered is the cost of it to our ancestors.

In Cornwall, there were those with links to the Scoboryo’s who were loyal to the crown such as Sir Bevil Grenville, Sir John Arundell of Trerice, Sir Richard Vyvyan and Sir Francis Godolphin, those who took up arms for the Parliamentarians were John St Aubyn and Richard Erisy, the fates of these Cornish men lay in the outcome of the wars. Out of these five men, the two Parliamentarians were generously rewarded, two of those who supported Charles were fined and lost (for a time) their estates. Only Sir Bevil Grenville lost his life.

We know that the civil wars put family against family and father against son and no better example of this is William Frederick Yeames's painting where a little boy in a royalist household is being spoken to by parliamentarians who ask the question "And When Did You Last See Your Father" which quite naturally puts the child in a difficult position and his family in a dangerous one.

These wars certainly placed friend against friend as the aforementioned Sir Bevil Grenville found.

Sir Bevill Grenville, despite being a Royalist, found his allegiances torn when his friend Sir John Eliot of St Germans was incarcerated, on more than one occasion in the Tower of London for his views on parliamentary right (and his refusal to pay his taxes) Eliot eventually died in the Tower and King Charles refused his son permission to bury his father in his homeland cruelly stating

"Let Sir John Eliot be buried in the church of that parish where he died."

All these men were dealing directly with the fall out of King Charles I's ideas of the Divine Right and his attempt to enforce it. The civil wars that raged between 1642 and 1651 resulted in the loss of over eighty thousand lives plus the hundreds of thousands who died from war-related diseases, ultimately though King Charles I would be held responsible and he would pay with his life.

So, this was England in early years of the 17th century, a country on the brink of civil war. Most of the landed families of Cornwall took the side of the king and this included the family of Arundel - St Columb Major as we have seen in the previous chapter, being so closely associated with the Arundel's, would most certainly be predominantly royalist. The village would not witness these wars first hand, the closest they would come to seeing any ‘action’ would be in 1646, however, the aforementioned Arundel family would suffer the consequences of their support of Charles I.

"Let Sir John Eliot be buried in the church of that parish where he died."

All these men were dealing directly with the fall out of King Charles I's ideas of the Divine Right and his attempt to enforce it. The civil wars that raged between 1642 and 1651 resulted in the loss of over eighty thousand lives plus the hundreds of thousands who died from war-related diseases, ultimately though King Charles I would be held responsible and he would pay with his life.

So, this was England in early years of the 17th century, a country on the brink of civil war. Most of the landed families of Cornwall took the side of the king and this included the family of Arundel - St Columb Major as we have seen in the previous chapter, being so closely associated with the Arundel's, would most certainly be predominantly royalist. The village would not witness these wars first hand, the closest they would come to seeing any ‘action’ would be in 1646, however, the aforementioned Arundel family would suffer the consequences of their support of Charles I.

Apart from the Arundels, no other family of great importance (that is who had influence or held a position of power in government over the Tamar) had their family seat in the area around St Columb Major. However, there were other wealthy families who had a ‘great’ house in the town but whose main family estates were elsewhere in Cornwall, the Vyvyans at Trewan, Noyes at Carnanton and the Hoblyn’s at Nanswhydan were three of them. Also living in the town were other wealthy families whose livelihood was not dependent on family connections or inheritance, these men such as the Paynter’s and the Gaverigan’s fortunes were self-made. But what of the Scoboryo’s?

It was during the reign of the first Tudor kings that the Scoboryo’s were landowners of some importance, their ancient lands in the west of Cornwall were sandwiched between the Bonython estate at Bonython and Vyvyan estate at Trelowarren in Mawgan in Meneage. However, by 1560 their large estate had passed out of the family via a marriage of the Scoboryo heiress to the aforementioned Vyvyan family.

By the middle of the 16th century both the Bonython's and the Vyvyan's had cadet branches of their families, the Bonythons were established at St Columb Minor and the Vyvyans at St Columb Major. The parish records for the villages show that the Scoboryo family were linked by marriage to the Bonython and Vyvyans from 1560 at the latest. It can be no coincidence that the Scoboryo’s, who now found themselves in a lower social class, can be found in St Columb Major living and working alongside their kinsmen.

By the middle of the 16th century both the Bonython's and the Vyvyan's had cadet branches of their families, the Bonythons were established at St Columb Minor and the Vyvyans at St Columb Major. The parish records for the villages show that the Scoboryo family were linked by marriage to the Bonython and Vyvyans from 1560 at the latest. It can be no coincidence that the Scoboryo’s, who now found themselves in a lower social class, can be found in St Columb Major living and working alongside their kinsmen.

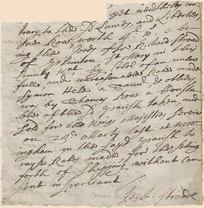

Although there is a record in the St Columb Major parish register of a Scoboryo marriage in 1541 and a birth of twin boys in 1554 there is no mention of a James Scoboryo at all, he arrived in the village in the middle of the 17th century, it is his marriage that is first mention of my Scoboryo family in this Cornish town. James Scoboryo and Joan Potter were my 9th great-grandparents, they arrived at the town’s Church of St Columba on a cold winters day in the February of 1640 to be married.