2nd February 2015: I would like to dedicate this family story to my dear Uncle Terry who sadly passed away a few months ago. I didn't know until today that he loved the River Gannel as much as I do.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Cornwall had grown prosperous from agriculture, unlike today, agriculture was the mainstay of the counties economy, an economy which was based on small farms, most with under one hundred acres of land that specialised in dairy, stock rearing and horticulture. Horses had replaced oxen and winter crops were grown and the potato was the staple diet of the poor. A thriving market gardening industry appeared towards the end of the 1900’s growing spring crops such as carrots, cabbages and onions.

It was during this period that my 4x great grandfather, William Mitchell, farmed over 90 acres of land on the west coast of Cornwall.

It was during this period that my 4x great grandfather, William Mitchell, farmed over 90 acres of land on the west coast of Cornwall.

The eighteenth century saw the end of the Stuart period and the beginning of the Georgian age, it was an age of expansion, an age of inventions that brought changes to the textile industry, the mining industry and in agriculture. In 1761, six years before the birth of William Mitchell, George III was crowned king of England. Remembered mostly for his spells of ‘madness’ he was also famous for his passionate interest in agriculture and because of this nicknamed Farmer George. It was during his reign that England underwent an agricultural revolution where men such as Jethro Tull from Berkshire and Robert Bakewell from Leicestershire are credited with improving the lives of those working on the land. During this time farming output almost doubled, an increase in the use of crops grown as food for animals allowed farmers to keep more livestock and this meant more meat was produced and sold in the markets to feed the growing population. This revolution saw the introduction of new systems of cropping and selective breeding but interestingly, it has been argued that this revolution did not happen at all, that the increase in farm production was a slow progress of events beginning in mid sixteenth century and ending in the eighteenth. This agricultural revolution occurred at the same time as the more famous Industrial Revolution and Cornwall could lay claim to at least seven inventors in engineering alone, men like Sir Humphrey Davey, Adrian Stephens, and Henry Trengrouse. These Cornish born engineers were at the forefront of the Industrial Revolution but it was mining engineer Richard Trevithick whose invention benefited both industry and agriculture.

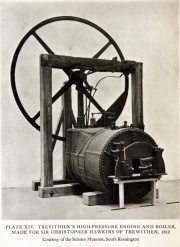

Trevithick’s new high pressure steam engine used three times more coal than James Watts steam engine, but it was more compact, this meant that it had it a greater range of use in areas such as the railways, at sea and in agriculture. Trevithick adapted his engine for agricultural purposes by attaching it to a rotating drum that separated the grain from the stalks that later became known as a threshing machine. There can be no doubt that new farming techniques and technology would eventually make life easier for the descendants of men like William Mitchell but what it gave with one hand it took with the other. By the time William was tending his ninety acres at Lescliston he and every farmer in England lost their rights to common lands under the enclosure system.

The society in which William lived and worked was still based on the old feudal system made up of labourers, tenant farmers and wealthy landowners, these landowners were no longer nobles but the ‘self made man’, the gentleman. It was these gentlemen who used the new Enclosure Act for financial gain, although you could argue that William Mitchell as a tenant farmer also benefited from the act as he could use it as a way to improve his holdings too, but it was the agricultural labourers who lost out, just like in Tudor times when families who had the least, lost the most. From the middle of the eighteenth century enclosure by parliamentary act was seen as the norm, in just over three hundred years over 5,000 enclosure bills were enacted which meant that just over a fifth of the total area of England, that is over six million acres, was in the hands of private individuals and it was one of these landholders, Sir Christopher Hawkins, who owned the land on which William Mitchell farmed.

Sir Christopher Hawkins family had been Cornish landowners since they purchased the Trewithen estate at Probus in 1715. Previously a courtier to Henry VIII, John Hawkins went on make his fortune from maritime trading when he moved to Cornwall in 1554. Christopher Hawkins eventually inherited many extensive estates and several profitable mines. At the age of 12, his father, Sir Thomas Hawkins, died in 1766 from an inoculation against smallpox. Sir Christopher later went on to become a philanthropist. He was involved in the clay mines of St Austell, opened new tin and copper mines, gave money to existing schools and built new ones. Sabine Baring Gould, a Cornish antiquarian thought him “ greedy for land purchases” and he is known to have boasted that he could ‘ride from one side of Cornwall to the other without setting hoof on another man’s land” but others considered him to be a benevolent landlord who was ‘‘never known to distrain for rent.’ However it seems his tenants saw him differently, suggesting that he was cautious and frugal giving rise to this rhyme about his estate:

“A large park without deer, A large cellar without beer, A large house without cheer, Sir Christopher Hawkins lives here”

Frugal Hawkins may have been, but he was quick to spot the potential of Richard Trevithick’s high-pressure steam engine. He became Trevithick’s patron and it was Hawkins who commissioned Trevithick's newly powered threshing machine. He was the first to use it, installing it at Trewithen to replace his cattle driven mill in the February of 1812.

The society in which William lived and worked was still based on the old feudal system made up of labourers, tenant farmers and wealthy landowners, these landowners were no longer nobles but the ‘self made man’, the gentleman. It was these gentlemen who used the new Enclosure Act for financial gain, although you could argue that William Mitchell as a tenant farmer also benefited from the act as he could use it as a way to improve his holdings too, but it was the agricultural labourers who lost out, just like in Tudor times when families who had the least, lost the most. From the middle of the eighteenth century enclosure by parliamentary act was seen as the norm, in just over three hundred years over 5,000 enclosure bills were enacted which meant that just over a fifth of the total area of England, that is over six million acres, was in the hands of private individuals and it was one of these landholders, Sir Christopher Hawkins, who owned the land on which William Mitchell farmed.

Sir Christopher Hawkins family had been Cornish landowners since they purchased the Trewithen estate at Probus in 1715. Previously a courtier to Henry VIII, John Hawkins went on make his fortune from maritime trading when he moved to Cornwall in 1554. Christopher Hawkins eventually inherited many extensive estates and several profitable mines. At the age of 12, his father, Sir Thomas Hawkins, died in 1766 from an inoculation against smallpox. Sir Christopher later went on to become a philanthropist. He was involved in the clay mines of St Austell, opened new tin and copper mines, gave money to existing schools and built new ones. Sabine Baring Gould, a Cornish antiquarian thought him “ greedy for land purchases” and he is known to have boasted that he could ‘ride from one side of Cornwall to the other without setting hoof on another man’s land” but others considered him to be a benevolent landlord who was ‘‘never known to distrain for rent.’ However it seems his tenants saw him differently, suggesting that he was cautious and frugal giving rise to this rhyme about his estate:

“A large park without deer, A large cellar without beer, A large house without cheer, Sir Christopher Hawkins lives here”

Frugal Hawkins may have been, but he was quick to spot the potential of Richard Trevithick’s high-pressure steam engine. He became Trevithick’s patron and it was Hawkins who commissioned Trevithick's newly powered threshing machine. He was the first to use it, installing it at Trewithen to replace his cattle driven mill in the February of 1812.

In 1872 the Hawkins family were ranked seventh on a list of wealthy Cornish landowners, with 12,119 acres of land, by this time William Mitchell was dead, as was Christopher Hawkins, but the 90 acres he originally held in 1841 was still farmed by members of his family.