Domesday and 13th Century Charters

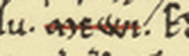

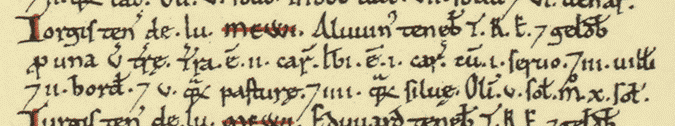

The Cornish language was spoken in large areas of Devon well after the Norman conquest, but it maybe that the inhabitants of Meavy spoke with a West Country/Wessex dialect of Middle English, a language used and written by King Alfred, this may have resulted in the confusion over the name of my ancestors settlement. As you can see in the Domesday book the name of the village can be read as Mewi.

By the beginning of the 12th century the Normans began to introduce a system of reclamation with the aim of clearing and cultivating waste land. They achieved this by granting small estates on the edges of moorland to those who would make good the land by farming and the raising of stock. These new ‘landowners’ would become free-tenants. Once again, the remoteness of the Meavy settlement was an advantage, it enabled the family to prosper. In return for their ‘good fortune’ they would make gifts of food, money and eventually land to their local church, it is in this, the gifting of land to the Priory of Plympton, that we get our first mention of this ancient family going under the surname of Mewi.

In a Charter dated 904, Edward the Elder granted land at Plympton to Asser, Bishop of Sherbourne in exchange for a monastery to be built at Plympton, this Anglo-Saxon collage housed a community of secular canons. According to the Domesday Book the college consisted of a Dean and four prebendaries. By 1121, the college's days were numbered, William Warelwast, Bishop of Exeter dissolved the collage in order to establish a house for Augustinian monks. This new build was Plympton Priory. Dedicated to St Peter and St Paul the priory is situated just seven miles south of Meavy.

Plympton Priory lies between Plymouth and the town of Plympton itself, and in its time it was the wealthiest monastic house in Devon and the fourth wealthiest establishment of the Augustinian Order in England and Wales. Under Warelwast’s successors the priory acquired much land, so much so its revenue exceeded that of its neighbour Tavistock Abbey. On the 1st March 1539, when it was dissolved in Henry VIII and Thomas Cromwell's purge of the monasteries of England, the priory’s revenue was calculated at £912 12s 8d. Many of the priory's fine Norman architectural stone work was scattered to the winds, a window formed part of a 20th century public house and its beautiful stone doorway found itself in Cornwall’s Roseland Peninsula, (much of this area was owned by the priory) and built into the Church of St Anthony in Roseland.

Plympton Priory lies between Plymouth and the town of Plympton itself, and in its time it was the wealthiest monastic house in Devon and the fourth wealthiest establishment of the Augustinian Order in England and Wales. Under Warelwast’s successors the priory acquired much land, so much so its revenue exceeded that of its neighbour Tavistock Abbey. On the 1st March 1539, when it was dissolved in Henry VIII and Thomas Cromwell's purge of the monasteries of England, the priory’s revenue was calculated at £912 12s 8d. Many of the priory's fine Norman architectural stone work was scattered to the winds, a window formed part of a 20th century public house and its beautiful stone doorway found itself in Cornwall’s Roseland Peninsula, (much of this area was owned by the priory) and built into the Church of St Anthony in Roseland.

A number of notable families, such as the Mandervilles, Vernons and Giffards were benefactors of Plympton Priory, Richard, Earl of Cornwall also took an interest. Eventually though, as these great families established their own religious houses and monies that once headed the way of Plympton soon diminished, and the priory had to rely on monies given to them by the tenants of these noble houses. The Meavy family, under Juhel of Totnes's successor, can be counted among the priory early benefactors.

The priory at Plympton was granted the right to gather as much wood as it needed to cook food, and this aided clearance of the land in accordance with the Norman new reclamation system, and this in turn provided land that was used to grow oats and wheat and enabled the priory to rear sheep for wool and meat. Originally, fresh water from a spring to the priory was carried via stone lined drains and later by aqueduct and conduit.

These charters and land grants are important because they show, not only who owned the land, but how the priory sustained itself. They were small pieces of evidence that show the workings of the kingdom as a whole. They confirmed tenures of land to the church and to nobility that included their rights and privileges.

The priory at Plympton was granted the right to gather as much wood as it needed to cook food, and this aided clearance of the land in accordance with the Norman new reclamation system, and this in turn provided land that was used to grow oats and wheat and enabled the priory to rear sheep for wool and meat. Originally, fresh water from a spring to the priory was carried via stone lined drains and later by aqueduct and conduit.

These charters and land grants are important because they show, not only who owned the land, but how the priory sustained itself. They were small pieces of evidence that show the workings of the kingdom as a whole. They confirmed tenures of land to the church and to nobility that included their rights and privileges.

There are a number of documents, that are dated between the reign of William Rufus through to the reign of Henry II, that feature the Meavy family in name. One can be viewed through the transference of land held by the aforementioned Judel of Totnes to the family of Roger de Nonant/Novant, and the second is a grant by one Walter Meavy.

The first document is a royal charter that links the Meavy family with the Nonant's through gift of a manor in 1168.

In 1123 Guy Nonant inherited the barony from his father, Roger Nonant who is listed as a benefactor of Plympton Priory. In a confirmation charter, Guy confirms his father’s gifts of land to Plympton Priory in free arms and this confirmation also states that his wife Mabilia gave the small manor of Scobbahill to the priory.

It was the Scobbahill gift that was the subject of legal action between one Walter Meavy and Plympton Priory in 1168/69. In the case, brought in Totnes before the Royal Justicars, Walter Meavy claimed that the land was his by hereditary right but he was not able to bring any evidence to ownership of the land. The canons of Plympton Priory responded that the land had been granted to them by Mabilia, the wife of Guy de Nonant and this was confirmed by Roger de Nonant, Guy’s son a heir. Roger confirmed his mother's gift had had a number of witnesses. Eventually, the case was found in favour of the Nonants, however a generation later the actions were conceded by Roger’s three sons, Guy, Henry and Baldwin.

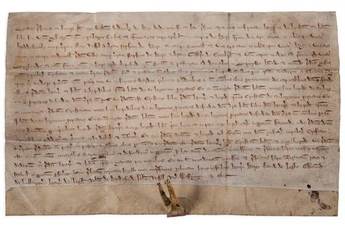

The second of the aforementioned documents relates to a number grants by Walter Meavy himself. One grant mentions land with a sluice that was gifted to the priory, and another that mentions a garden together with a marsh meadow. A third grant made in the name of Walter Meavy refers to a the gifting of two furlongs of land from his manor for the use of the priory and eight acres of land for the use of the king. The following the first part of that confirmation, dated 1202, when one Robert de Islington was Prior of Plympton Priory.

The first document is a royal charter that links the Meavy family with the Nonant's through gift of a manor in 1168.

In 1123 Guy Nonant inherited the barony from his father, Roger Nonant who is listed as a benefactor of Plympton Priory. In a confirmation charter, Guy confirms his father’s gifts of land to Plympton Priory in free arms and this confirmation also states that his wife Mabilia gave the small manor of Scobbahill to the priory.

It was the Scobbahill gift that was the subject of legal action between one Walter Meavy and Plympton Priory in 1168/69. In the case, brought in Totnes before the Royal Justicars, Walter Meavy claimed that the land was his by hereditary right but he was not able to bring any evidence to ownership of the land. The canons of Plympton Priory responded that the land had been granted to them by Mabilia, the wife of Guy de Nonant and this was confirmed by Roger de Nonant, Guy’s son a heir. Roger confirmed his mother's gift had had a number of witnesses. Eventually, the case was found in favour of the Nonants, however a generation later the actions were conceded by Roger’s three sons, Guy, Henry and Baldwin.

The second of the aforementioned documents relates to a number grants by Walter Meavy himself. One grant mentions land with a sluice that was gifted to the priory, and another that mentions a garden together with a marsh meadow. A third grant made in the name of Walter Meavy refers to a the gifting of two furlongs of land from his manor for the use of the priory and eight acres of land for the use of the king. The following the first part of that confirmation, dated 1202, when one Robert de Islington was Prior of Plympton Priory.

“To all the faithful to whom the present writing shall have come, William de Mewi health in the Lord. Your community should know that Walter de Mewi, the

grandfather of Gilda, my wife, by the assent and consent of Wido, his son and heir, the father forsooth of the aforesaid G, my wife, for his safety and for that of all

his ancestors and successors give to the church of the Holy Apostles, Peter and Paul of Plimton, and to the canons serving God there, two furlongs of land from

his manor of Mewi, in free and in all respects quiet and perpetual alms, and eight acres of land, which ought to do the service of the King only. Forsooth as much

as eight acres of the same manor of Mewi ought to make. And four men then holding the same land, forsooth the sons of Alwin, whose names are Osbert,

Streswold, Edwin and Seward, with their wives and children.

grandfather of Gilda, my wife, by the assent and consent of Wido, his son and heir, the father forsooth of the aforesaid G, my wife, for his safety and for that of all

his ancestors and successors give to the church of the Holy Apostles, Peter and Paul of Plimton, and to the canons serving God there, two furlongs of land from

his manor of Mewi, in free and in all respects quiet and perpetual alms, and eight acres of land, which ought to do the service of the King only. Forsooth as much

as eight acres of the same manor of Mewi ought to make. And four men then holding the same land, forsooth the sons of Alwin, whose names are Osbert,

Streswold, Edwin and Seward, with their wives and children.

This confirmation grant makes interesting reading, it shows that Meavy was still populated with the descendants of the Anglo-Saxon thanes who held the land during the reign of Edward the Confessor. Out of the four thanes, only Alwin’s family remain and are given, along with the land, to the priory.

Alwin, as you can see in the Domesday book held one of the five manors at Meavy, his landholding were 2 ploughlands and seven sheep, 0.12 lord's lands, five furlongs of pasture, four furlongs of woodland on which there were three villagers, two smallholders and one slave. It is not clear when the Meavy family rose in importance above that of Alwin the king’s thane, but a change of position there was and this is more than likely to have resulted from a marriage of a daughter of Alwin to a son of Meavy, and as time passed the family 'officially' held most of the Domesday manors at Meavy.

From the time the Domesday commissioners arrived in the manors of Meavy, and the signing of the above grant, six kings, including William the Conqueror had ruled England. They were the conqueror’s two sons William Rufus and Henry I, followed by Stephen, Henry II, Richard I and John.

From the time the Domesday commissioners arrived in the manors of Meavy, and the signing of the above grant, six kings, including William the Conqueror had ruled England. They were the conqueror’s two sons William Rufus and Henry I, followed by Stephen, Henry II, Richard I and John.