The Beginnings of a New Era

The exact date the Meavy’s began to build their new manor house is not known, however a number of interior features put the date to between 1202 and 1243. The house that we see today, was altered and extended in the 16th and 17th centuries, only the great parlour with its grand fireplace, (the chimney stack can be seen from the outside) and two granite mullion windows remains of what was once a family home. Like many barton farms in Devon the property was encompassed by a stone wall.

The exterior of the house has “Stone rubble walls, rendered at the front, a gable ended slate roof, three tall granite ashler stacks with drip courses and mounded rims, one at each end” can be seen to the left of the church in the aerial photograph below.

Compared to the size of the manor houses of the Tudor period, the 13th century manor house of William and Gilda Meavy was quite small, a farm house really, but a good example of what money could buy within the social group the Meavy’s belonged. Meavy house had its new great parlour, the next step up from their Anglo-Saxon great hall, that was still the focus of the family's daily life. It was in this period great that halls began to develop in every kind of residence, from the likes of the Meavy’s home, to the merchant houses and the castles of their lords. Interestingly, the great hall has continued to be an important part of the English home, today we often refer to an old manor house as a hall, even the area that joins our entrance to the rest of the rooms within our own homes is called a hall. The Meavy’s home would grow and increase in size as the years passed, but still a smaller version of the manor houses of the those who were wealthier and who had been rewarded for deeds done on behalf the the crown. The size of the house would reflect this, a way of impressing your importance on other members of the nobility; the grander the manor the more self-important a lord would feel. The growth of the manor house can be seen up and down the country, Charnney Manor house in Oxfordshire, Stokesay Castle in Shropshire and Ingtham Mote in Kent are all fine examples of the progression the the manor house, and as each successive generation took up residence the bigger the house became. As a family, the Meavy’s would reach their peak in the reign of Richard II, the family home however would continue to be improved until the reign of Elizabeth I.

Adjacent to the house is the Parish Church of St Peters that was founded by the Meavy family and built around the same time as their manor house. Built out of Rodborough stone and granite, again, as with their manor house, there are a number of 13th century windows that are still in place. The oldest architectural feature of Meavy church is the square north pier to the chancel arch and a number of carved human heads on the ceilings. The horns were a later addition and are thought to be Norman as are the carvings at the top of the columns on the churches west door. The clock tower is fifteenth century and built or at least added to by the Drake family, descendants of the brother of Sir Francis Drake, long after the last Meavy was buried within the church grounds.

Along with the mullion windows, other features in the church that are linked to the time of Walter Meavy is a stone stoup, a basin used for holy water that is fixed in the church porch, we can only imagine what Walter, Wido, William and Gilda Meavy thought as they looked upon its ugly little face. Still surviving from the time of Alice Meavy, the last of the Meavy’s who frequented the church, is a 14th century cross slab that is now embedded in the gable end of the south porch. It is likely that this is a wayside cross, a sister cross to five over crosses in the area, a marker that invited passing monks, who journeyed to and from Plympton Priory, to stop for prayer and to rest their weary feet.

Wayside crosses began to appear in England between the ninth and fifteenth centuries, not only as a reminder to the traveller of their faith, but as a mark of reassurance as they journeyed in what must have been difficult terrain.

Meavy parish church is dedicated to St Peter, with a date of dedication set to 1122, however there is some doubt about this. Anglo-Saxon and Norman churches are known to have been dedicated to St Peter, but Devon usually favoured St Andrew, St Michael, St Mary and All Saints and records show that there are no reference to St Peter until after the mid 18th century leading historians to think that the dedication of Meavy’s Church was linked with the village feast day, the first Monday after St Peter’s day, the 29th June.

Meavy parish church is dedicated to St Peter, with a date of dedication set to 1122, however there is some doubt about this. Anglo-Saxon and Norman churches are known to have been dedicated to St Peter, but Devon usually favoured St Andrew, St Michael, St Mary and All Saints and records show that there are no reference to St Peter until after the mid 18th century leading historians to think that the dedication of Meavy’s Church was linked with the village feast day, the first Monday after St Peter’s day, the 29th June.

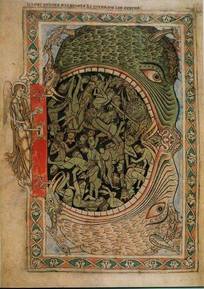

The role of the medieval church played a far greater part in the life of is parishioners that it does today, in medieval England the church would had dominated everybody’s life, everybody believed in God, heaven and hell, they were terrified that if they deviated from the path of goodness they were headed to hell, images of

damnation were everywhere. The image below for instance, depicts an angel locking the door to what is known as a Hell's Mouth. Often illustrated as a monster, in this case a giant sea creature, whose mouth never closes, we can see the agonies and the suffering of the poor tormented souls inside. It is a gateway to hell, the fiery depths of medieval damnation, it is a good example of how medieval people like the Meavy’s saw heaven and hell as separate places. If you look, the door with its lock lies exactly on the border which could be said to represent the area just outside hell which of course is purgatory and the angel stands in the margin which maybe the human world or heaven, he locks the door to those who are damned for all time in hell which takes up the centre space. Is it any wonder then, that those with money, smoothed their passage to heaven with gifts to the church, with a build such as St Peter’s, the Meavy's I imagine, would have been welcomed with open arms.

damnation were everywhere. The image below for instance, depicts an angel locking the door to what is known as a Hell's Mouth. Often illustrated as a monster, in this case a giant sea creature, whose mouth never closes, we can see the agonies and the suffering of the poor tormented souls inside. It is a gateway to hell, the fiery depths of medieval damnation, it is a good example of how medieval people like the Meavy’s saw heaven and hell as separate places. If you look, the door with its lock lies exactly on the border which could be said to represent the area just outside hell which of course is purgatory and the angel stands in the margin which maybe the human world or heaven, he locks the door to those who are damned for all time in hell which takes up the centre space. Is it any wonder then, that those with money, smoothed their passage to heaven with gifts to the church, with a build such as St Peter’s, the Meavy's I imagine, would have been welcomed with open arms.

William and Gilda Meavy, maybe carrying their newly born son, their elder son toddling along behind, would have been frequent visitors, kneeling at the altar praying for the remission of the sins and giving thanks to God for what he had done and they hoped would continue to do. By the middle of the 13th century William can be found in a position of importance, in 1238 he is recorded has being a Justice of the Peace in the Crown Pleas of Devon Eyre.

An Eyre is a large area of land and William was, in effect, a circuit judge acting in the name of the king, in this position he was one of the highest ranking magistrates within the medieval forest law system, presiding over 'the court of justice-seat' in a court that sat every three years, in this position he would have been paid about 100 marks. William would have had control of the state of the forests and its officers and would have had to impose penalties on lawbreakers, the fines he imposed on forest offences was a major source of revenue for the king, however the outcry against these laws eventually bared fruit, by 1225 a new charter banned capital punishments for forest offences such as poaching and hunting protected deer, it also exempted those within the forest from fines for erecting buildings and creating new arable land. Eventually, by 1242 landowner were granted permission (on a payment of 5000 marks paid into the royal treasury) to continue with deforestation. As no part of the Meavy estate was touched by the forest of Dartmoor, William Meavy may not have been troubled, but if he did, we can only wonder how this conflict of interest was handled.

An Eyre is a large area of land and William was, in effect, a circuit judge acting in the name of the king, in this position he was one of the highest ranking magistrates within the medieval forest law system, presiding over 'the court of justice-seat' in a court that sat every three years, in this position he would have been paid about 100 marks. William would have had control of the state of the forests and its officers and would have had to impose penalties on lawbreakers, the fines he imposed on forest offences was a major source of revenue for the king, however the outcry against these laws eventually bared fruit, by 1225 a new charter banned capital punishments for forest offences such as poaching and hunting protected deer, it also exempted those within the forest from fines for erecting buildings and creating new arable land. Eventually, by 1242 landowner were granted permission (on a payment of 5000 marks paid into the royal treasury) to continue with deforestation. As no part of the Meavy estate was touched by the forest of Dartmoor, William Meavy may not have been troubled, but if he did, we can only wonder how this conflict of interest was handled.

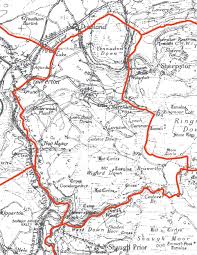

In the same year William is recorded as a Justice of the Peace, we hear for the first time a mention of one Richard Meavy as a landowner in the Rodborough hundreds, that piece of land was probably Knolle, a small manor, now gone, that lay north of Meavy, somewhere in the vicinity of Horrabridge and Walkhampton. Five years later, Richard Meavy appears again as holding Meavy, Knolle, Hoo Meavy, Gratton, and Loveton. At the same time holding lands at Goodameavy is one William Meavy. The relationship of Richard Meavy at Knolle and William Meavy at Good a Meavy to William at the manor of Meavy is not specified, however the transference of Meavy and five other manors to Richard in 1243 we can suppose that he was his eldest son and heir. William at Good a Meavy may well have been his brother.

With a new generation of Meavy lords, their chief manor continued to be Meavy and this was held by the family outright, however the manors of Goodameavy and Hoo Meavy were held as a half share with others under differing overlords. Hoo Meavy was held under Stephen Furneaux by Richard Meavy and William Giffard and Goodameavy was held by under Walter de Pomeroy by William Meavy and William Pomeroy.

The Pomeroys and the Giffards had their feet firmly rooted in the red soil of Devon from as early as 1068, the progenitor of the Pomeroys was Ralf de Pomaria, hewas a knight from La Pommeraye near Falaise in Normanday, who had been granted the manor of Berry, along with fifty-six others in 1068 for services at the Siege of Exeter. By 1086, their manor of ‘Beri’ was worth £12 a year, which was a third more than the Meavy’s first overload Judel’s barony at Totnes. On their climb upwards, this family would eventually leave behind their unfortified manor house for a far grander one. Berry Pomeroy Castle was held by this family until the mid 16th century when it was purchased by Sir Edward Seymour, Lord Protector of England. The Giffard’s at Weare Giffard, were a cadet branch of 1st Earl of Buckingham, whose manor was situated at just northwest of Great Torrington. The Giffard family line ended, as the Meavy’s would with the birth of a daughter's. Families like the Giffard's and the Pomeroy’s would be looking upwards to other wealthier and more powerful families to aid their climb on the ladder of success, not downwards to the Meavy’s, and for a while they would be successful. You could argue that the Meavy’s were successful too, because they were not destined to lose everything when the debt owed in payment of successes was called in. Unlike the Pomeroy’s, the Meavy’s would not be caught up in the violent inter family feuds that plagued Devon in the mid 14th century, and whose decline has it’s roots in the 15th century in the Wars of the Roses. The Meavy’s lower social status, below that of nobility, enabled them to keep their heads and to die in the comfort of their own beds as opposed to lose them in battles so far away from home.

Of course, there is no evidence to say how William Meavy died, but we can see in documentation where it states that he was deceased by the mid 13th century. We already know William had received the Meavy estates from his father in law Walter Meavy around 1202, therefore William would have held the manor for over forty years. Of the fate of Williams’s wife Gilda, I have found no information.

With a new generation of Meavy lords, their chief manor continued to be Meavy and this was held by the family outright, however the manors of Goodameavy and Hoo Meavy were held as a half share with others under differing overlords. Hoo Meavy was held under Stephen Furneaux by Richard Meavy and William Giffard and Goodameavy was held by under Walter de Pomeroy by William Meavy and William Pomeroy.

The Pomeroys and the Giffards had their feet firmly rooted in the red soil of Devon from as early as 1068, the progenitor of the Pomeroys was Ralf de Pomaria, hewas a knight from La Pommeraye near Falaise in Normanday, who had been granted the manor of Berry, along with fifty-six others in 1068 for services at the Siege of Exeter. By 1086, their manor of ‘Beri’ was worth £12 a year, which was a third more than the Meavy’s first overload Judel’s barony at Totnes. On their climb upwards, this family would eventually leave behind their unfortified manor house for a far grander one. Berry Pomeroy Castle was held by this family until the mid 16th century when it was purchased by Sir Edward Seymour, Lord Protector of England. The Giffard’s at Weare Giffard, were a cadet branch of 1st Earl of Buckingham, whose manor was situated at just northwest of Great Torrington. The Giffard family line ended, as the Meavy’s would with the birth of a daughter's. Families like the Giffard's and the Pomeroy’s would be looking upwards to other wealthier and more powerful families to aid their climb on the ladder of success, not downwards to the Meavy’s, and for a while they would be successful. You could argue that the Meavy’s were successful too, because they were not destined to lose everything when the debt owed in payment of successes was called in. Unlike the Pomeroy’s, the Meavy’s would not be caught up in the violent inter family feuds that plagued Devon in the mid 14th century, and whose decline has it’s roots in the 15th century in the Wars of the Roses. The Meavy’s lower social status, below that of nobility, enabled them to keep their heads and to die in the comfort of their own beds as opposed to lose them in battles so far away from home.

Of course, there is no evidence to say how William Meavy died, but we can see in documentation where it states that he was deceased by the mid 13th century. We already know William had received the Meavy estates from his father in law Walter Meavy around 1202, therefore William would have held the manor for over forty years. Of the fate of Williams’s wife Gilda, I have found no information.

Under William, the Meavy family had gone from holding three manors to at least six. Added to Meavy, Hoo Meavy and Good a Meavy, were the manors of Loveton, Gratton and Knolle, only the manor of Knolle lay outside the boundaries of Meavy Parish. However by 1296 the Meavy’s held only four, ironically, the manors lost were Hoo Meavy and Goodameavy, two of the three manors original Anglo-Saxon manors.

The years in between 1243 and 1296 were a time of great change, members of the nobility began to think that they deserved a say in the running of the country, and by 1258 they got just that, that year England opened its first parliament. Representing Devon were four members of the counties more important families, William Courtaney of Musbury, Geoffrey Dynham of Hartland, William de Bickleigh of Bickleigh and Roger de Cockinham of Cockingham all headed north.

Henry III, as other previous monarchs had done regularly used council meetings to discuss affairs of state, in Henry’s reign these meeting resulted in the early formation of parliament. During the thirteenth century these assemblies were always summoned by the king and generally he consulted only a small council, but by requiring the wealthy barons to help govern, Henry strengthened their powers and in time they came to call themselves the Great Council. However, many of these men grew to think that the king must consult the council and when decisions were made without their consultation they developed a sense of being excluded from the work of government in which they felt entitled to participate. The king insisted that attendance at sessions of the ‘great council’ were compulsory and that it was a duty not a privilege and this, inevitably, ended in trouble. Many of Henry’s barons had become a law unto themselves and they were now seeing Henry as weak, David Carpenter writes that Henry

“failed as a ruler due to his naivety and inability to produce realistic plans for reform.”

Henry did not help himself either, his personal extravagances had resulted in large taxes and a major fall out with his brother in law and one time friend Simon de Montfort did not help matters. In 1238, in a blatant piece of favouritism towards de Montfort, Henry approved de Montfort’s marriage to his twenty three year old sister Eleanor, both Henry and de Montfort chose to ignore the condemnation of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the protest Henry and Eleanor's brother, Richard of Cornwall, made a song and dance of the whole episode but was eventually bought on side for a couple of bags of gold. Henry also appointed de Montfort as Governor of Gascony, a mistake that cost him dearly. In Gascony, Montfort was disliked, but he was powerful and he abused his position and this forced Henry to intervene. On Montfort's return to England, he too perceived Henry as weak and with the barons aching for a fight, Simon de Montfort stepped in to take charge.

The years in between 1243 and 1296 were a time of great change, members of the nobility began to think that they deserved a say in the running of the country, and by 1258 they got just that, that year England opened its first parliament. Representing Devon were four members of the counties more important families, William Courtaney of Musbury, Geoffrey Dynham of Hartland, William de Bickleigh of Bickleigh and Roger de Cockinham of Cockingham all headed north.

Henry III, as other previous monarchs had done regularly used council meetings to discuss affairs of state, in Henry’s reign these meeting resulted in the early formation of parliament. During the thirteenth century these assemblies were always summoned by the king and generally he consulted only a small council, but by requiring the wealthy barons to help govern, Henry strengthened their powers and in time they came to call themselves the Great Council. However, many of these men grew to think that the king must consult the council and when decisions were made without their consultation they developed a sense of being excluded from the work of government in which they felt entitled to participate. The king insisted that attendance at sessions of the ‘great council’ were compulsory and that it was a duty not a privilege and this, inevitably, ended in trouble. Many of Henry’s barons had become a law unto themselves and they were now seeing Henry as weak, David Carpenter writes that Henry

“failed as a ruler due to his naivety and inability to produce realistic plans for reform.”

Henry did not help himself either, his personal extravagances had resulted in large taxes and a major fall out with his brother in law and one time friend Simon de Montfort did not help matters. In 1238, in a blatant piece of favouritism towards de Montfort, Henry approved de Montfort’s marriage to his twenty three year old sister Eleanor, both Henry and de Montfort chose to ignore the condemnation of the Archbishop of Canterbury and the protest Henry and Eleanor's brother, Richard of Cornwall, made a song and dance of the whole episode but was eventually bought on side for a couple of bags of gold. Henry also appointed de Montfort as Governor of Gascony, a mistake that cost him dearly. In Gascony, Montfort was disliked, but he was powerful and he abused his position and this forced Henry to intervene. On Montfort's return to England, he too perceived Henry as weak and with the barons aching for a fight, Simon de Montfort stepped in to take charge.

Ten years later this action culminated in the Provisions of Oxford, a law that served to limit Henry’s power. Henry’s refusal to accept the Provisions of Westminster the following year saw Montfort’s power base grow rapidly, and by 1263 he was all but wearing the crown. On the 14th of May 1264 at the Battle of Lewes, Henry, his son the future Edward I, and Richard, Duke of Cornwall were all taken prisoner, however, in 1265 the tables were turned, and it was at the Battle of Evesham, on the 4th August, that Simon de Montfort died a grisly death. By 1267 the problems between Henry and his barons, that were based on the 1258/9 provisions, had still not settled down and a new set of laws were needed. On the 18th or 19th of November 1267 in a Parliament at Marlborough the twenty nine chapters, that made up the Statute of Marlborough, was passed.The kings last few years saw his power restored and it was a relatively peaceful one following the signing of the Dictum of Kenilworth. Henry was sensible enough to pass many of de Montfort's ideas and changes to government, and this act was brought into play by the end of October 1266.

King Henry III’s reign was a long one, he was king of England for fifty six years, his time as our country's monarch was one of the most important and significant reigns in our history and much overlooked. Henry was the first English king to be crowned as a child, he improved the educational system in England, he was a lover of art and architecture and it was Henry who ordered the rebuilding of Westminster Abbey in the Gothic style we see today.

In 1239, the year we first hear of Richard, William Meavy’s son and heir, Henry’s queen Eleanor of Provence, had given birth to their son Edward, later Edward I. By the time he had been on the throne of England for twenty-four years Richard Meavy had died, as had his son and grandson - what I wonder was the tragedy that befell the family in those few years?

King Henry III’s reign was a long one, he was king of England for fifty six years, his time as our country's monarch was one of the most important and significant reigns in our history and much overlooked. Henry was the first English king to be crowned as a child, he improved the educational system in England, he was a lover of art and architecture and it was Henry who ordered the rebuilding of Westminster Abbey in the Gothic style we see today.

In 1239, the year we first hear of Richard, William Meavy’s son and heir, Henry’s queen Eleanor of Provence, had given birth to their son Edward, later Edward I. By the time he had been on the throne of England for twenty-four years Richard Meavy had died, as had his son and grandson - what I wonder was the tragedy that befell the family in those few years?