|

Joseph Taylor

2x Great Grandfather (or not?) |

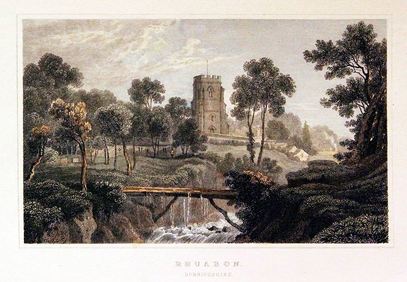

Wales had always relied on its agricultural output for its wealth and employment but with the arrival of the Industrial Revolution it saw a rapid economic growth in the hundred years between 1750 and 1850. The development of copper and iron smelting had seen increased usage of this mineral become prevalent in both the north and the south of the country. But it was coal mining that was to become the single industry that we associate with Wales. Initially, coal seams were exploited to provide energy for local metal industries but, with the opening of canal systems, and later the railways, welsh coal mining saw a boom in its demand in England as well. The call for more iron and coal saw families move from a life in agriculture to a life in mining, the Taylor’s were one of these. It was in small mining village of Ruabon Denbighshire that Joseph Taylor’s grandparents were born.

George Borrow, an English writer, travelled extensively and wrote of his experiences, of his visit to Raubon he wrote in his book Wild Wales:

“Rhiwabon … a large village about half way between Wrexham and Llangollen. I observed in this place nothing remarkable, but an ancient church. My way from hence lay nearly west. I ascended a hill, from the top of which I looked down into a smoky valley. I descended, passing by a great many collieries, in which I observed grimy men working amidst smoke and flame. At the bottom of the hill near a bridge I turned round. A ridge to the east particularly struck my attention; it was covered with dusky edifices, from which proceeded thundering sounds, and puffs of smoke.”

From their farm, just outside the village of Ruabon, Joseph’s grandparents would have seen the village just as it was described in Borrow's book which was written in 1850 four years before Joseph Taylor was born. His grandparents, William and Esther Taylor, were hill farmers and can be found farming twelve acres of land outside the village. Both William and Esther were born at the turn of the century and by 1851 they had had ten children, eight boys and two girls. John, the eldest was Joseph’s father.

William and Esther were tenant farmers, they employed no servants as there were more than enough family members to handle the workload. Children who grew up on farms would have spent there adolescence at home with little or no pay, so by the time they reached adulthood they would have known nothing else, as a result they too took on farm tenancies but this was not the case regarding the Taylor children. As they grew the farm would not have been able to sustain ten adults and this forced the sons to look for work elsewhere. Although farming was one of the main forms of work in rural Wales it was not the only one and as we know mining was another. Ruabon and its surrounding areas had large deposits of iron and coal which were mined extensively and it was these mines that nearly all the sons of William and Ester went to work. The main employer in Ruabon was the British Iron Company who operated ironwork's and collieries from 1825 to 1887 and it was here that the Taylor’s son were probably employed.

During the following twenty years the family gradually dispersed, John left the area, four of his siblings stayed in Ruabon but of the other five nothing is known. William and Esther continued on their farm well into their seventies. William later became a local Methodist preacher.

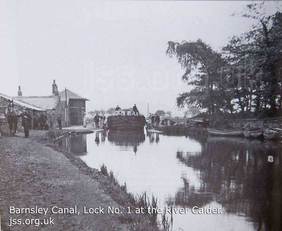

At the age of twenty four, Williams eldest son John was working as a iron labourer, he would be involved in excavating the iron ore or working the furnaces. Much of what was excavated here and in the other mines in the area was exported by canal over the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct on the Shropshire Union Canal to the many iron foundries situated in Manchester. The 1851 census tells us that John was single but had already met and made arrangements for his marriage. As we know John was a labourer but it maybe that at some point he was employed on the canal boats that carried the iron ore to Manchester and this is probably how he met Elizabeth who was born there. Within two months of their marriage Elizabeth was pregnant with their first child. Encouraged by what he saw and heard in the foundries in Manchester and Worcester he realised that employment in the town would offer more security and better prospects than that of Ruabon were at least two of the mines had flooded and had to close. In early 1852 with the birth of their son John, the family moved into a house on Woodside in Worcester where in 1854 Joseph Taylor was born. John may have worked for a short time for Thomas Clunes whose owned iron and brass foundries in the town and who were building a new foundry which was to become known as the Vulcan Iron Works this would have created many new jobs in the area but John had already looked for and found work in the coal mines of Brierley Hill Staffordshire.

“Rhiwabon … a large village about half way between Wrexham and Llangollen. I observed in this place nothing remarkable, but an ancient church. My way from hence lay nearly west. I ascended a hill, from the top of which I looked down into a smoky valley. I descended, passing by a great many collieries, in which I observed grimy men working amidst smoke and flame. At the bottom of the hill near a bridge I turned round. A ridge to the east particularly struck my attention; it was covered with dusky edifices, from which proceeded thundering sounds, and puffs of smoke.”

From their farm, just outside the village of Ruabon, Joseph’s grandparents would have seen the village just as it was described in Borrow's book which was written in 1850 four years before Joseph Taylor was born. His grandparents, William and Esther Taylor, were hill farmers and can be found farming twelve acres of land outside the village. Both William and Esther were born at the turn of the century and by 1851 they had had ten children, eight boys and two girls. John, the eldest was Joseph’s father.

William and Esther were tenant farmers, they employed no servants as there were more than enough family members to handle the workload. Children who grew up on farms would have spent there adolescence at home with little or no pay, so by the time they reached adulthood they would have known nothing else, as a result they too took on farm tenancies but this was not the case regarding the Taylor children. As they grew the farm would not have been able to sustain ten adults and this forced the sons to look for work elsewhere. Although farming was one of the main forms of work in rural Wales it was not the only one and as we know mining was another. Ruabon and its surrounding areas had large deposits of iron and coal which were mined extensively and it was these mines that nearly all the sons of William and Ester went to work. The main employer in Ruabon was the British Iron Company who operated ironwork's and collieries from 1825 to 1887 and it was here that the Taylor’s son were probably employed.

During the following twenty years the family gradually dispersed, John left the area, four of his siblings stayed in Ruabon but of the other five nothing is known. William and Esther continued on their farm well into their seventies. William later became a local Methodist preacher.

At the age of twenty four, Williams eldest son John was working as a iron labourer, he would be involved in excavating the iron ore or working the furnaces. Much of what was excavated here and in the other mines in the area was exported by canal over the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct on the Shropshire Union Canal to the many iron foundries situated in Manchester. The 1851 census tells us that John was single but had already met and made arrangements for his marriage. As we know John was a labourer but it maybe that at some point he was employed on the canal boats that carried the iron ore to Manchester and this is probably how he met Elizabeth who was born there. Within two months of their marriage Elizabeth was pregnant with their first child. Encouraged by what he saw and heard in the foundries in Manchester and Worcester he realised that employment in the town would offer more security and better prospects than that of Ruabon were at least two of the mines had flooded and had to close. In early 1852 with the birth of their son John, the family moved into a house on Woodside in Worcester where in 1854 Joseph Taylor was born. John may have worked for a short time for Thomas Clunes whose owned iron and brass foundries in the town and who were building a new foundry which was to become known as the Vulcan Iron Works this would have created many new jobs in the area but John had already looked for and found work in the coal mines of Brierley Hill Staffordshire.

Joseph Taylor was born by the time Queen Victoria had been on the throne for sixteen years and the country as a whole had seen

“long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence”

England may have been fairly stable but there was trouble abroad with the war in the Crimea in 1854 and in India in 1857, but the vast majority of people in England were living on or below the bread line. Middle class and upper class Victorians made up approximately fifteen percent of population. Middle class families were considered wealthy and held professional positions such as doctors, lawyers, bankers, factory owners, merchants, and shopkeepers. These families lived in large, comfortable houses. This was in sharp contrast to the overcrowded and unhealthy conditions in which the Taylor’s found themselves when they arrived in Brierley Hill. Wealthy landowning families like the Earls of Dudley, who owned all the mines in Brierley Hill, made vast profits from the mines while the work force barely scraped by.

Brierley Hill had a large number of quarries and collieries that supplied the factories in the Black Country with coal and building materials and it also had numerous factories of its own that made use of narrow canal locks on Dudley Canal, on which hundreds of canal boats passed though containing coal and limestone. This area was known locally as the Delph and it was here 1857 that the family settled.

“long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence”

England may have been fairly stable but there was trouble abroad with the war in the Crimea in 1854 and in India in 1857, but the vast majority of people in England were living on or below the bread line. Middle class and upper class Victorians made up approximately fifteen percent of population. Middle class families were considered wealthy and held professional positions such as doctors, lawyers, bankers, factory owners, merchants, and shopkeepers. These families lived in large, comfortable houses. This was in sharp contrast to the overcrowded and unhealthy conditions in which the Taylor’s found themselves when they arrived in Brierley Hill. Wealthy landowning families like the Earls of Dudley, who owned all the mines in Brierley Hill, made vast profits from the mines while the work force barely scraped by.

Brierley Hill had a large number of quarries and collieries that supplied the factories in the Black Country with coal and building materials and it also had numerous factories of its own that made use of narrow canal locks on Dudley Canal, on which hundreds of canal boats passed though containing coal and limestone. This area was known locally as the Delph and it was here 1857 that the family settled.

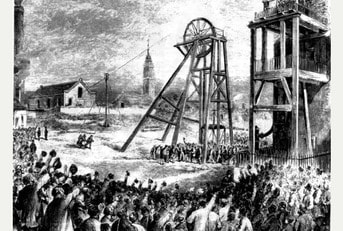

Elizabeth was pregnant again by the time the family arrived here, by the end of 1857 a daughter Eliza was born followed two years later by another son Benjamin. John Taylor and his two older sons John and Joseph, and eventually Benjamin, worked under dreadful conditions and as mentioned earlier mines had become bigger and deeper which brought new hazards for the miners as they risked life and limb working in confined spaces breathing in stale air and coal dust. Mining accidents were very common in the 19th century, certainly John Taylor and his sons were in great danger every day of their lives.

In November 1872 twenty two miners lost their lives in one colliery in Brierly Hill. The Brierley Hill Advertiser of Saturday 23rd May 1857 reports of the death of a 16 year old and the suffocation of John M'clue.

“The 16 year old was William Burns who fell to his death at 5pm on the 21st of May at Lower Pit, Kingswinford. He had been placing timber

in the skips to send down to the pit, and got pulled down when his hand became entangled in the chain. On the same day another

a accident claimed the life of John M'clue who died of suffocation at Number 1 Pit at Moor Lane in Brierley Hill”

For the next ten years the Taylor family lived and worked in the mines of Brierley Hill and it is hard to say what each individual really felt. Happy or not this was their way of life and for most there was no getting away from it. Mining communities were close knit, one family looked out for another and helped out if they could. By 1867 Joseph's mother Elizabeth had given birth to two more children, a son William and daughter Anna and in 1868 Elizabeth was once again pregnant. This was possibility that last ‘happy’ event the family witnessed as tragedy was looming in the shadows.

John was destined not to see his last child reach adulthood as his death is recorded as being in 1869 at the age of 42, the cause of it is not known. I thought for a while that he may have died in the Nine Lock Pit accident of 1869 when thirteen men were trapped at the bottom of a deep pit shaft for over a week but it seems that was not the case. It was more than likely that John died from a mine related condition such as emphysema or in one of the many smaller disasters involving single death that were very common and that passed into time unnoticed.

In November 1872 twenty two miners lost their lives in one colliery in Brierly Hill. The Brierley Hill Advertiser of Saturday 23rd May 1857 reports of the death of a 16 year old and the suffocation of John M'clue.

“The 16 year old was William Burns who fell to his death at 5pm on the 21st of May at Lower Pit, Kingswinford. He had been placing timber

in the skips to send down to the pit, and got pulled down when his hand became entangled in the chain. On the same day another

a accident claimed the life of John M'clue who died of suffocation at Number 1 Pit at Moor Lane in Brierley Hill”

For the next ten years the Taylor family lived and worked in the mines of Brierley Hill and it is hard to say what each individual really felt. Happy or not this was their way of life and for most there was no getting away from it. Mining communities were close knit, one family looked out for another and helped out if they could. By 1867 Joseph's mother Elizabeth had given birth to two more children, a son William and daughter Anna and in 1868 Elizabeth was once again pregnant. This was possibility that last ‘happy’ event the family witnessed as tragedy was looming in the shadows.

John was destined not to see his last child reach adulthood as his death is recorded as being in 1869 at the age of 42, the cause of it is not known. I thought for a while that he may have died in the Nine Lock Pit accident of 1869 when thirteen men were trapped at the bottom of a deep pit shaft for over a week but it seems that was not the case. It was more than likely that John died from a mine related condition such as emphysema or in one of the many smaller disasters involving single death that were very common and that passed into time unnoticed.

Elizabeth’s baby was born before April 1869 and was named David. It is unknown if John saw the boy come into the world but we know that John was dead by the end of the year leaving Elizabeth a widow and seven children fatherless, the elder three children were able to bring money into the home so they was not destitute. Elizabeth and the children would have been well supported by the mining community but none the less life must have been tremendously hard.

The 1871 census shows that the family of John Taylor were still together and living at 92 Delph Road which more or less backed onto the east side of the Delph’s nine locks. Within a few months of the census the elder son John had married and had moved from the family home leaving Joseph as the main bread winner. Joseph would have been a miner but Benjamin, who was twelve, would be a hurrier, his job was to pull or push the carts loaded with coal, the trapper, which no doubt would have been William job, would sit in a small cutting waiting for the hurriers to approach. Boys like William would then open the trapdoors to allow the hurrier and his cargo through. The trappers also opened the trapdoors to provide ventilation in some locations.

The 1871 census shows that the family of John Taylor were still together and living at 92 Delph Road which more or less backed onto the east side of the Delph’s nine locks. Within a few months of the census the elder son John had married and had moved from the family home leaving Joseph as the main bread winner. Joseph would have been a miner but Benjamin, who was twelve, would be a hurrier, his job was to pull or push the carts loaded with coal, the trapper, which no doubt would have been William job, would sit in a small cutting waiting for the hurriers to approach. Boys like William would then open the trapdoors to allow the hurrier and his cargo through. The trappers also opened the trapdoors to provide ventilation in some locations.

Following the death of their father, the family were to suffer another blow with the death of David who was aged just three, the loss of both the father and younger child was, I believe, too much for Elizabeth to bear for she too was dead shortly after leaving the family in a state of utter hopelessness and in a town that had inspired the following old verse:

When Satan stood on Brierley Hill

And far around him gazed,

He said, "I never more shall feel

At Hell's fierce flames amazed."

During the Industrial Revolution Brierley Hill had become heavily industrialised and heavily polluted and was in this ‘hell hole’ in 1875 that Joseph Taylor found himself, at the head of the family, despairing and probably very lonely he continued on. After the death of David the family had moved from The Delph to Potters Street which is just a short distance on the west side of the Dudley canal locks. It maybe that Joseph’s mother moved to this address and it was here she died after which Joseph was forced to take on the tenancy.

Coal companies provided houses for their workforce as it was necessary for the miners to be close to their work as no form of transport was available but living conditions varied considerably, the quality of the housing was often dependent on the size and prosperity of the company. The house in which Joseph lived was on a terrace. The front door opened from the pavement into a living room which had a fireplace and measured 10ft by 11ft. The back room was the scullery (kitchen) which measured 9ft by 10ft and had a range for cooking, a stone sink and the staircase leading to two bedrooms upstairs. Outside was a communal yard, at the bottom of which was a toilet and middens which were used as ash pits for faeces and kitchen waste. Inside the house, hung on a nail on the back wall would be the bath.

Joseph was in his early twenties when his mother died, he became head of the household and responsible for four younger siblings but within a few years only Eliza and William remained. Anna had left for domestic post in Dudley and Benjamin disappears without trace, without them to provide extra income Joseph must have been in dire straits, for he was the only person in the household who was working as both his younger brother and sister were unable to find work.

When Satan stood on Brierley Hill

And far around him gazed,

He said, "I never more shall feel

At Hell's fierce flames amazed."

During the Industrial Revolution Brierley Hill had become heavily industrialised and heavily polluted and was in this ‘hell hole’ in 1875 that Joseph Taylor found himself, at the head of the family, despairing and probably very lonely he continued on. After the death of David the family had moved from The Delph to Potters Street which is just a short distance on the west side of the Dudley canal locks. It maybe that Joseph’s mother moved to this address and it was here she died after which Joseph was forced to take on the tenancy.

Coal companies provided houses for their workforce as it was necessary for the miners to be close to their work as no form of transport was available but living conditions varied considerably, the quality of the housing was often dependent on the size and prosperity of the company. The house in which Joseph lived was on a terrace. The front door opened from the pavement into a living room which had a fireplace and measured 10ft by 11ft. The back room was the scullery (kitchen) which measured 9ft by 10ft and had a range for cooking, a stone sink and the staircase leading to two bedrooms upstairs. Outside was a communal yard, at the bottom of which was a toilet and middens which were used as ash pits for faeces and kitchen waste. Inside the house, hung on a nail on the back wall would be the bath.

Joseph was in his early twenties when his mother died, he became head of the household and responsible for four younger siblings but within a few years only Eliza and William remained. Anna had left for domestic post in Dudley and Benjamin disappears without trace, without them to provide extra income Joseph must have been in dire straits, for he was the only person in the household who was working as both his younger brother and sister were unable to find work.

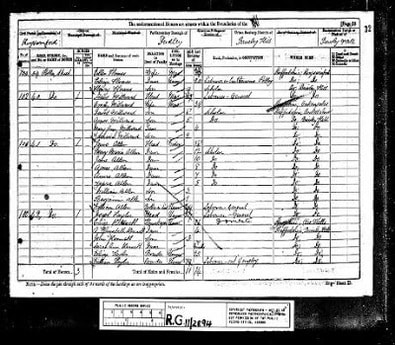

It was, I believe, around this time that Joseph met Eliza Kennett, when and where they met we will never know, but what we do know was that she was living on Chapel Street, Brierley Hill in the August of 1880. At some point during the following seven months, Eliza moved into the same house as Joseph, probably as a sub-tenant, and along with her came her three children Alice Elizabeth aged 4, John Henry aged 3, and Sarah Ann aged 7 months. Professor Rebecca Probert who has made a study of cohabitation writes 'very occasionally a sexual relationship between a woman and a man sharing an address can be inferred from the presence of a child and a subsequent marriage.' But this was rare, and childbearing outside marriage was not generally the result of a cohabiting relationship. It is clear that most of the mothers of illegitimate babies were not living with the father.' This has proved to be true in the case of Eliza and her three children. Surprisingly, on the census in April of the following year, Joseph is stated to be the 'father' of Eliza Kennett's children.

It is commonly thought that on the day of the census the enumerator would visit each household and take down all information personally, this was not the case. A few days before he would deliver what was known as a Household Schedule and the head of the household would fill it in. If the members of the household were illiterate then the enumerator would do that for them. Probably the whole of the household of 42 Potter Street was illiterate, we know that Eliza defiantly was because she signed with a cross when registering the births of her three children, so it was more than likely that the enumerator filled in their household schedule. Joseph is listed as head of the household, and as mentioned earlier, it states that Eliza’s three children were his, but their births certificates state otherwise, the actual fathers of all three are unknown, the census also states that Eliza and William Taylor are boarders when they were Joseph’s siblings.

'

It is commonly thought that on the day of the census the enumerator would visit each household and take down all information personally, this was not the case. A few days before he would deliver what was known as a Household Schedule and the head of the household would fill it in. If the members of the household were illiterate then the enumerator would do that for them. Probably the whole of the household of 42 Potter Street was illiterate, we know that Eliza defiantly was because she signed with a cross when registering the births of her three children, so it was more than likely that the enumerator filled in their household schedule. Joseph is listed as head of the household, and as mentioned earlier, it states that Eliza’s three children were his, but their births certificates state otherwise, the actual fathers of all three are unknown, the census also states that Eliza and William Taylor are boarders when they were Joseph’s siblings.

'

The definition of a household and the terms lodger or boarder can cause problems for family historians. Even when the census was being taken, enumerators, despite instructions, often imposed their own view as to how relationship terms should be treated within the household. So we cannot say for certain that it was Joseph's choice, Eliza’s insistence, or the enumerator error that the dynamics of 42 Potter Street were enumerated wrongly.

Who then was saying what when the enumerator asked his questions?

It is easy to think that the arrival of Eliza Kennett must have been a godsend for Joseph, he was struggling financially, his brother and sister were unemployed and the three of them were dependent on Joseph's one wage. The question is what were the real motives and who was the instigator of the original suggestion for the Kennett’s to move into the house on Potters Street? The most plausible reasons were quite simply money and shelter. Joseph needed money from another source and Eliza needed shelter and stability for her three children. If it was purely financial how did Joseph think that he would benefit from introducing four extra individuals into his home when only one of them could pay their way? Did he not think he would he would be better off offering the rooms to a couple of employed single men or a married couple? Or was there an emotional attachment, we do know that it wasn't long before at all before they were living as 'man and wife. Once again Professor Probert has an answer for this, she suggests that for the Victorians, 'relationships outside marriage tended to be surreptitious rather than openly acknowledged. The poor, dependent upon landlords, employers, and occasionally charity, needed to maintain a good reputation just as much as the wealthy, if not more so.'

Life was hard for men like Joseph, working as he did surround by men in a back breaking job it is easy to imagine that he was the archetypal northern man, straight talking and to the point, a man who found it hard to express his emotions. Eliza, on meeting him for the first time, this is maybe how he appeared but she soon would have realised that he was far from this, underneath he was as low as a man could go, vulnerable and emotionally depressed and presented with a ‘sob story’ he might as well have been a moth drawn to the light.

Of course, Joseph's character is hard to define as is what he thought of Eliza. So was he a ‘decent fellow’ who felt he could offer this woman and her children a new life, flattered by the advances of a rather experienced woman, or a pushover eventually succumbing to her womanly wiles, bewitched or bullied we will never know. A domineering, strong, single-minded woman Eliza most certainly was, an episode in her later life proves this. Did she bully her way into Joseph's life? Was he her ‘meal ticket’? Or was Joseph a man taking advantage of what Eliza had to offer, the opportunity of having someone to cook and clean for him and at the end of the day the hope of a warm bed? Was Eliza trying to cover up her past indiscretions for conformity's sake by stating that Joseph was her children's father, if this was the case then why not tell another lie and say that they were married? Had she tried to isolate the brother and sister in an attempt to separate him from his family is that why Joseph's brother and sister said to be boarders when they were defiantly his siblings? It is my opinion that Eliza may have taken control of that household fairly early on, willingly or unwillingly Joseph was named as the father of her three illegitimate children. The 1881 census raises too many questions, none of which will ever be answered satisfactorily.

Regardless of anything said before Joseph chose to stay with Eliza. We know that he had four children with her after 1887 but there was a gap of six years between the birth of her last illegitimate child and the birth of Joseph's daughter which suggests that their physical relationship did not start till 1886, and therefore before that date, they were simply lodging, but that was not the case. According to the 1911 census, it seems that Eliza had nine children and not seven as I thought. Eliza it seems was pregnant twice between 1881 and 1886, there is no record of these children so we must assume that they died as infants and we must also assume and hope that they were fathered by Joseph because if they were not he most certainly was a push over!

By 1887 Joseph, along with pregnant Eliza and her three children, had moved to Royston in the County of Yorkshire.

Who then was saying what when the enumerator asked his questions?

It is easy to think that the arrival of Eliza Kennett must have been a godsend for Joseph, he was struggling financially, his brother and sister were unemployed and the three of them were dependent on Joseph's one wage. The question is what were the real motives and who was the instigator of the original suggestion for the Kennett’s to move into the house on Potters Street? The most plausible reasons were quite simply money and shelter. Joseph needed money from another source and Eliza needed shelter and stability for her three children. If it was purely financial how did Joseph think that he would benefit from introducing four extra individuals into his home when only one of them could pay their way? Did he not think he would he would be better off offering the rooms to a couple of employed single men or a married couple? Or was there an emotional attachment, we do know that it wasn't long before at all before they were living as 'man and wife. Once again Professor Probert has an answer for this, she suggests that for the Victorians, 'relationships outside marriage tended to be surreptitious rather than openly acknowledged. The poor, dependent upon landlords, employers, and occasionally charity, needed to maintain a good reputation just as much as the wealthy, if not more so.'

Life was hard for men like Joseph, working as he did surround by men in a back breaking job it is easy to imagine that he was the archetypal northern man, straight talking and to the point, a man who found it hard to express his emotions. Eliza, on meeting him for the first time, this is maybe how he appeared but she soon would have realised that he was far from this, underneath he was as low as a man could go, vulnerable and emotionally depressed and presented with a ‘sob story’ he might as well have been a moth drawn to the light.

Of course, Joseph's character is hard to define as is what he thought of Eliza. So was he a ‘decent fellow’ who felt he could offer this woman and her children a new life, flattered by the advances of a rather experienced woman, or a pushover eventually succumbing to her womanly wiles, bewitched or bullied we will never know. A domineering, strong, single-minded woman Eliza most certainly was, an episode in her later life proves this. Did she bully her way into Joseph's life? Was he her ‘meal ticket’? Or was Joseph a man taking advantage of what Eliza had to offer, the opportunity of having someone to cook and clean for him and at the end of the day the hope of a warm bed? Was Eliza trying to cover up her past indiscretions for conformity's sake by stating that Joseph was her children's father, if this was the case then why not tell another lie and say that they were married? Had she tried to isolate the brother and sister in an attempt to separate him from his family is that why Joseph's brother and sister said to be boarders when they were defiantly his siblings? It is my opinion that Eliza may have taken control of that household fairly early on, willingly or unwillingly Joseph was named as the father of her three illegitimate children. The 1881 census raises too many questions, none of which will ever be answered satisfactorily.

Regardless of anything said before Joseph chose to stay with Eliza. We know that he had four children with her after 1887 but there was a gap of six years between the birth of her last illegitimate child and the birth of Joseph's daughter which suggests that their physical relationship did not start till 1886, and therefore before that date, they were simply lodging, but that was not the case. According to the 1911 census, it seems that Eliza had nine children and not seven as I thought. Eliza it seems was pregnant twice between 1881 and 1886, there is no record of these children so we must assume that they died as infants and we must also assume and hope that they were fathered by Joseph because if they were not he most certainly was a push over!

By 1887 Joseph, along with pregnant Eliza and her three children, had moved to Royston in the County of Yorkshire.

The village of Royston is in the West Riding of Yorkshire and lies on the Barnsley Canal. From the late nineteenth century, many families from the Black Country migrated to Royston, attracted by work at Monckton Pit. Such was the impact on Royston by the influx of people that the place was occasionally referred to as 'Little Staffordshire'. By 1888 the “Taylor’s” had settled in Royston and that year Joseph’s daughter Edith was born followed by Ernest in 1890, the census of the following year tells us Joseph was employed as a colliery labourer at the Monckton Colliery and the family were living on what is still known as Monckton Row. In 1893 Joseph’s daughter Ethel was born. In 1896 a son was born who was named Arthur but that year is the last time we hear of Joseph.

Lies were told at beginning of Joseph's life with Eliza and it seems, lies were told at the end too, but by whom? On the 1901 census, Eliza states that she is married, and no record of their marriage can be found, but Joseph doe’s not appear at their home the night of that census and cannot be found elsewhere. He is named as the father at the marriage of Eliza’s son John Henry Taylor in 1904, but by 1911 Eliza states that she is a widow, no record of his death can be found. As mentioned Joseph is not listed on the 1901 census at his family home nor is he listed as working/living elsewhere and there is no reference to his death between then and 1911, in theory, Joseph has disappeared completely from 1896 onwards, being named on John Henry’s marriage certificate does not mean that he was alive in 1904.

From the age of five Joseph Taylor spent his years in the darkness of the Welsh coal mines followed by nine in other mines, moving from one coal mining town to another. He spent a number of years supporting his mother and siblings after the death of his father and watched his mother as she grieved for the death of David and then watched as she died of a broken heart! He stayed, while the rest of his brothers and sisters moved on. The final fifteen years of his life was spent with a domineering woman who probably said one thing and did another.

So what happened to poor Joseph after 1896? I don’t know! and I have been unable to find out, but I do have an awful feeling that no one really cared.

In the years I have been researching my family history there are a few ancestors who I love and cannot bear to leave others I don’t like at all. Joseph, who is not related to me, fits into the first category. Instinctively I feel that Joseph was a kind, well meant and gentle man, some may call his character weak as there is no evidence of him being anything other than subservient kowtowing to Eliza from the minute she arrived with her three children on his doorstep.

I would like to dedicate the Taylor story to Joseph Taylor, a man who gave a family a name and brought up nine children three or ‘four’ of who were not his. Earlier I used the word subservient and by this, I meant “too eager to obey” but it also means something positive which is “to help to achieve something or bring something about”. This is exactly what Joseph Taylor did for my ancestors, his being there for John Henry and his gentleness I feel we're one of his qualities that made the rest of us what we are today.

The Taylor Children That Were Not Joseph's - Alice Elizabeth, John Henry, and Sarah Ann

As I have said earlier these three children were illegitimate and had moved with their mother into Joseph Taylor’s home in 1881. They all spent their formative years in Yorkshire and it is where they lived, married, and had children of their own.

Like the generations gone before all the females continued in the housewife and baby-making business and the males all went into the darkness of the coal mines.

The Taylor Children That Were Joseph's - Edith, Ernest, Ethel and maybe Arthur.

“The Cottons all lived in house near my grandparents also living with them was a Mrs Cook and Doris Cotton.”

Williams was indeed born in Royston to Francis Cook. Francis had been married to one John Cook and had the above name Lily and a son Alvin. We do not know what happened to John but Charlie was born in 1927 and lived and worked alongside the Taylor family. Charles Williams Snr had come to England in 1914 from Barbados. He was a miner who worked with my granddad. Granddad said Charlie was a big man who could “brace up” the coal face without machinery and knock wood into place with his head! What a wonderful story. The last child to be born to Edith was Doris in 1920 and it was said, again by the ever knowledgeable great aunt, that Edith died in childbirth and the child was brought up by her younger sister Ethel. Doris was married a Fredrick Freear.

We do not know the exact circumstances of what happened next in the life of Ernest but it can only be described as a tragedy. The story was told to me by the same great aunt who I have relied on for most of my information with the later Taylor’s.

“ Uncle Arthur was called up for the army and when his mother found out she was beside herself. Albert her favourite, she made it plain that she didn’t want him to go. Uncle Ernie went in his place and was killed by a sniper's bullet. His mother on hearing the news of his death never accepted it and for the rest of her life waiting for him to return home”

Here we see yet another bullying tactic used by Eliza Kennett to get her way.

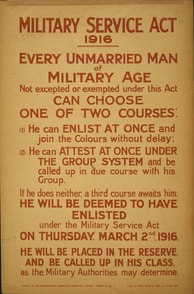

At the onset of the first world war, England had seen many of its young men leave to fight for their country. Many of these men from the coal mining regions joined infantry divisions, it was known that these divisions would incur heavy losses and with the need for more coal, men with skills like Ernest and Arthur were needed at home, even so by end of 1915 over a fifth of all miners had left coal-mining and enlisted in the army. The Defense of the Realm Act was introduced, which allowed the government to take over the coal mines, thus stemming the flow of men like Ernest, Arthur, and John Henry Taylor leaving an important industry. Also by the end of that year voluntary recruitment had slowed down and many men had decided to stay at home. To compensate for this The Military Service Act was introduced in early 1916, it specified that men from

“18 to 41 years old were liable to be called up for service in the army unless they were married, widowed with children, serving in the Royal Navy, a minister of religion, or working in one of a number of reserved occupations."

The second Act in May 1916 extended liability for military service to married men, and the third Act in 1918 extended the upper age limit to 51.”

Lies were told at beginning of Joseph's life with Eliza and it seems, lies were told at the end too, but by whom? On the 1901 census, Eliza states that she is married, and no record of their marriage can be found, but Joseph doe’s not appear at their home the night of that census and cannot be found elsewhere. He is named as the father at the marriage of Eliza’s son John Henry Taylor in 1904, but by 1911 Eliza states that she is a widow, no record of his death can be found. As mentioned Joseph is not listed on the 1901 census at his family home nor is he listed as working/living elsewhere and there is no reference to his death between then and 1911, in theory, Joseph has disappeared completely from 1896 onwards, being named on John Henry’s marriage certificate does not mean that he was alive in 1904.

From the age of five Joseph Taylor spent his years in the darkness of the Welsh coal mines followed by nine in other mines, moving from one coal mining town to another. He spent a number of years supporting his mother and siblings after the death of his father and watched his mother as she grieved for the death of David and then watched as she died of a broken heart! He stayed, while the rest of his brothers and sisters moved on. The final fifteen years of his life was spent with a domineering woman who probably said one thing and did another.

So what happened to poor Joseph after 1896? I don’t know! and I have been unable to find out, but I do have an awful feeling that no one really cared.

In the years I have been researching my family history there are a few ancestors who I love and cannot bear to leave others I don’t like at all. Joseph, who is not related to me, fits into the first category. Instinctively I feel that Joseph was a kind, well meant and gentle man, some may call his character weak as there is no evidence of him being anything other than subservient kowtowing to Eliza from the minute she arrived with her three children on his doorstep.

I would like to dedicate the Taylor story to Joseph Taylor, a man who gave a family a name and brought up nine children three or ‘four’ of who were not his. Earlier I used the word subservient and by this, I meant “too eager to obey” but it also means something positive which is “to help to achieve something or bring something about”. This is exactly what Joseph Taylor did for my ancestors, his being there for John Henry and his gentleness I feel we're one of his qualities that made the rest of us what we are today.

The Taylor Children That Were Not Joseph's - Alice Elizabeth, John Henry, and Sarah Ann

As I have said earlier these three children were illegitimate and had moved with their mother into Joseph Taylor’s home in 1881. They all spent their formative years in Yorkshire and it is where they lived, married, and had children of their own.

- Alice Elizabeth was born in 1876 her father is unknown. At the age of four, she was living with her mother and Joseph Taylor at 41 Potter Street Brierley Hill. By the time Alice was fourteen her mother had had three children with Joseph and she was living with them and unemployed. Two years later we see history repeat itself when Alice gave birth to a son whose father was unknown and who she named John Thomas. John was born in 1893 and went by the surname of Taylor. The following year, just as her mother had done, Alice met a man, one Fred Clarke, who was willing to marry her and bring up John as his own. They were married and two years later Alice gave birth to her first child with Fred Clark, a daughter Louisa followed by Dorothy, Lillian, Alice, and finally Harold. Fred worked within the mining community as a Pit Horse Keeper and the family lived at Holroyd Colliery Yard, and it was here that Alice died in the first week of March 1907 at the young age of 30. Her burial took place on the 17th of that month. Fred went on to marry again in 1908, his new wife was Laura Mable Kennett with whom he had a daughter Violet the following year. On the 1911 census, Alice's son John is still living with his step-father but by now going by the surname Clark.

- Sarah Ann was born in 1880 on Chapel Street Brierley Hill, she too was illegitimate and it is not known if her father was the same man who had fathered her sister and brother. She was seven months old when her mother moved in with Joseph Taylor and she was probably told that he was her father. In 1901 she had married George Shepard, a miner from Shropshire living in Royston, on the census of that year they were living with her mother in Royston. Within a year Sarah gave birth to her first daughter Alice Thurza who married Walter Mann, two unknown children born between 1903 and 1907 both of who had died in infancy. That same year Joseph was born followed by Edith May in 1909. In 1911 the family were living in Royston.

Like the generations gone before all the females continued in the housewife and baby-making business and the males all went into the darkness of the coal mines.

The Taylor Children That Were Joseph's - Edith, Ernest, Ethel and maybe Arthur.

- Edith was born in the tiny village of Monckton which is just outside Havercroft in 1888, and her younger sister Ethel was born in 1894 in Royston where the family finally settled By 1907 Edith had met and married Fred Cotton, a coal miner, and given birth to her first child Ernest. By 1911 Edith had a second child Edith Annie, they were living at the home of her mother in Royston. Three more sons followed, Albert in 1911 and Harold in 1914, Arthur (Arkie) in 1916 and finally Doris in 1920. A family story links the Cottons to Charlie Williams, Britain's first black stand-up comedian. (In all the years I have been researching my family history there have been rather a lot of exciting family stories. After discovering the truth I have found that dates are sometimes wrong and things embellished slightly but they have never been wrong.) In this case, Charlie Williams was not linked by blood but he was indeed linked to my family by marriage. Arkie, Edith’s younger son had married one Lily Cook, Lily was Charlie Williams half-sister. William's father was known in Royston as “Black Charlie” an awful term that we thankfully would not use today. When I spoke with a great-great aunt she said

“The Cottons all lived in house near my grandparents also living with them was a Mrs Cook and Doris Cotton.”

Williams was indeed born in Royston to Francis Cook. Francis had been married to one John Cook and had the above name Lily and a son Alvin. We do not know what happened to John but Charlie was born in 1927 and lived and worked alongside the Taylor family. Charles Williams Snr had come to England in 1914 from Barbados. He was a miner who worked with my granddad. Granddad said Charlie was a big man who could “brace up” the coal face without machinery and knock wood into place with his head! What a wonderful story. The last child to be born to Edith was Doris in 1920 and it was said, again by the ever knowledgeable great aunt, that Edith died in childbirth and the child was brought up by her younger sister Ethel. Doris was married a Fredrick Freear.

- Ethel was born in 1894 and was six years younger than Edith and said to be a bit “la de da”. She married someone by the surname of Merille, apart from these few facts nothing is known of her at all.

- Ernest and Arthur, like their sisters, were born in Havercroft and raised in Royston. Ernest was born in 1890 and Arthur in 1897. Ernest would have started work at the local colliery at the age of fourteen his brother was to follow him seven years later. By 1911 Ernest was twenty-one and Arthur fifteen, together they worked at Monckton Colliery as underground pony drivers for the next eight years until the outbreak of the First World War.

We do not know the exact circumstances of what happened next in the life of Ernest but it can only be described as a tragedy. The story was told to me by the same great aunt who I have relied on for most of my information with the later Taylor’s.

“ Uncle Arthur was called up for the army and when his mother found out she was beside herself. Albert her favourite, she made it plain that she didn’t want him to go. Uncle Ernie went in his place and was killed by a sniper's bullet. His mother on hearing the news of his death never accepted it and for the rest of her life waiting for him to return home”

Here we see yet another bullying tactic used by Eliza Kennett to get her way.

At the onset of the first world war, England had seen many of its young men leave to fight for their country. Many of these men from the coal mining regions joined infantry divisions, it was known that these divisions would incur heavy losses and with the need for more coal, men with skills like Ernest and Arthur were needed at home, even so by end of 1915 over a fifth of all miners had left coal-mining and enlisted in the army. The Defense of the Realm Act was introduced, which allowed the government to take over the coal mines, thus stemming the flow of men like Ernest, Arthur, and John Henry Taylor leaving an important industry. Also by the end of that year voluntary recruitment had slowed down and many men had decided to stay at home. To compensate for this The Military Service Act was introduced in early 1916, it specified that men from

“18 to 41 years old were liable to be called up for service in the army unless they were married, widowed with children, serving in the Royal Navy, a minister of religion, or working in one of a number of reserved occupations."

The second Act in May 1916 extended liability for military service to married men, and the third Act in 1918 extended the upper age limit to 51.”

Why then did Ernest go to war when he need not? And why was Arthur called up when he shouldn’t have been? Sadly there is no one answer to these questions, it could have been any number of things. Stigma played a big part in recruitment in both wars whole streets were signed up at the same time, it would be obvious if someone didn’t go! But this did not apply to the Taylor's community where everyone was employed in the colliery one way or another or at least fit into the other exemption categories, there would have been no embarrassment, it was their duty to stay. What we have to remember is that a good job was done by the government pushing patriotism, adventure, and ‘German bashing’. Also, the rules governing conscription were not strictly adhered to, fourteen and fifteen-year-olds regularly signed up. We know that Eliza was devastated when she heard the news about the call-up and we also know that she was a single-minded, strong-willed woman, did she use her powers of persuasion on Ernest as she had on Joseph years earlier? Or maybe Ernest simply wanted to protect his younger brother. Was it guilt that caused her to react the way she did when she found Ernest had died? We will never know what happened but what we do know is that their lives were shattered.

Arthur lived into his seventies, he never married and never moved away from home.

Arthur lived into his seventies, he never married and never moved away from home.