|

Godehute de Tosny

c 1126 - 1186 |

Godehute de Tosny was one of three surviving granddaughters of Anglo-Saxon Earl Waltheof of Huntingdon and his wife Judith of Lens, the niece of William the Conqueror. Waltheof held lands as far north as Fadmoor in Yorkshire and as far south as Tottenham before the arrival of the Normans in 1066. For siding with the conqueror, he was able to keep his possessions and his title. Waltheof was also granted the hand in marriage of the aforementioned Judith who brought to the marriage the fourteen manors she had been granted after the conquest. By 1076 Waltheof was dead and Judith’s holdings steadily increased, by 1086 she was holding over two hundred across ten counties. Waltheof’s title of Earldom of Huntingdon passed to his son in law, the husband of his elder daughter Maud. Maud and her younger sister Adalize shared their mother’s estates and these were added to those already held by their respective husbands Simon de Senlis and Ralph de Tosny. Both families would go on to make their small mark in English history and in the case of Maud and Simon in Scotland’s too. The Tosny’s, in name at least, survived to the beginning of the 14th century.

Adalize and Ralph de Tosny had, according to Orderic Vitalis, two sons and indicates that there were several daughters, one of whom was Godehute. This name had been used three times before in the Tosny family, so naturally there has been some confusion, historians continually attributing events in these women's life to each other. William of Jumieges, who lived through the Norman Conquests, stated that Godehute was married to Robert of Neufbourg, the son of Henry Beaumont the Earl of Warwick and Robert of Torigini, a 12th-century chronicler, writes that Godehute was married to Baldwin of Jerusalem. Torigini had the marriage of Godehute to Baldwin correct except that this Godhute was, in fact, the sister of Ralph de Tosny and therefore our Godehute’s aunt. Who the other Godehute (who did marry Robert of Nerfborug) was I have yet to discover. Adalize’s daughter Godehute was in fact married to William Mohun, Lord of Dunster in Somerset. We take this fact from the usual sources, charters, obits and land grants.

It is from documents such as these that we can trace the lives of medieval women like Godehute, sadly anything else they achieved during their lifetimes goes unrecorded. The first reference to Godehute comes from 1168. That year Henry II imposed a tax on landowners in an effort to raise money to help pay for the marriage of his daughter Matilda to Henry, the Duke of Saxony. Henry expected each lord was to pay his share promptly. At that time William Mohun of Dunster held forty-six manors in total, Mohun stated that he agreed to pay what was due on forty-one manors - forty that were his by inheritance and one that he had acquired by marriage, but he refused to pay tax on ‘five and a half knights fees’ which he stated were ‘of new feoffment’ and therefore he should not be expected to pay. Mohun didn’t pay the tax in his lifetime, whether his heirs were forced to pay is not known. This one little revolt against the powers of the king shows us an important thing that William’s wife, Godehute de Tosny brought only a single manor to their marriage - that of Brinkley in Cambridgeshire. Brinkley had been held by Judith of Lens and had passed to her daughter Adalize, along with Whittleford and Kirtling on her marriage to Ralph de Tosny, it was calculated, funnily enough, as being five and a half knights fees.

A knight’s fee, a holding enough to support a man and his family, probably measured between two and ten hides (about 120 acres) and was thought to be central to the idea of English feudalism, a system of government that in truth was not as regimented as we have been lead to believe - that is a system organised by rank, with a set of agreed rules, where the king ruled and protected his country, his barons supplied the knights for the army in times of war and the peasants did all the rest. The medieval person did not talk of a feudal system, in fact, the term 'feudal' was used only as far back as the eighteenth century in reference to out of date and unfair laws. However, the Conqueror's Domesday Book of 1086 did list what each county had in terms of land and stock and who held it, therefore it is not hard to see where we got the idea of feudalism from. It was into this world that Godehute was born

A knight’s fee, a holding enough to support a man and his family, probably measured between two and ten hides (about 120 acres) and was thought to be central to the idea of English feudalism, a system of government that in truth was not as regimented as we have been lead to believe - that is a system organised by rank, with a set of agreed rules, where the king ruled and protected his country, his barons supplied the knights for the army in times of war and the peasants did all the rest. The medieval person did not talk of a feudal system, in fact, the term 'feudal' was used only as far back as the eighteenth century in reference to out of date and unfair laws. However, the Conqueror's Domesday Book of 1086 did list what each county had in terms of land and stock and who held it, therefore it is not hard to see where we got the idea of feudalism from. It was into this world that Godehute was born

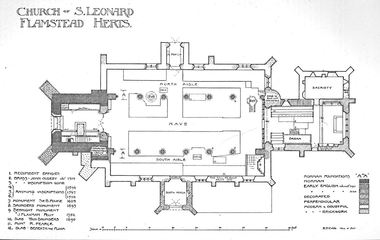

Godehute was one of six children all born before 1126, probably at her father's manor of Flamstead, a small village in Hertfordshire, which you can see in the images above. Positioned just a few miles from St Albans and standing on a ridge over a valley it is possible to see the River Ver and the old Roman road that we know as Watling Street. Flamstead had been granted to Godehute’s father Ralph de Tosny who, in his time, had been both a friend and foe of William the Conqueror. He was rewarded for his support in Normandy in the 1050’s and at Hastings in 1066. At first, he received a number of small manors in three counties and later he would be granted lands in four other counties. However, it was Flamstead that was the capital of the Tosny baroney.

The Tosny manor house would have stood a stone's throw from what is now the Parish Church of St Leonards, which stands on the site of a ninth-century Saxon chapel. St Leonard’s Church tower, nave and chancel dates from around 1120 and is the oldest part of the building, but it is the thirteenth and fourteenth-century remodeling that makes St Leonards what you see today which includes a number of wonderful medieval wall paintings covered up with whitewash plaster during the Reformation.

The size of the St Leonard's nave suggests that at the time of Godehute’s birth St Leonards was of some importance, for a nave of this size is commonly found in much larger country churches. These few areas within the church are all that remain of the building in which the Tosny’s worshiped. Godehute may have been one of the first babies to be baptised at the church, we can imagine her being carried, maybe wrapped in a wool blanket, under the larger arch and along the nave as you can see in the illustration below.

Godehute, as previously mentioned was one of six children, the only girl among five boys. The children’s father was absent for the greater part of their infancy being with King Henry I on campaign in Normandy in 1104, at the Battle of Tinchebray in 1106 and in support of the king during the revolt against him in 1119. Godehute’s mother was the daughter of a Countess, and therefore the care of the children was left to others. High ranking women like Adelize would not have breastfed, so it is unlikely that Adelize would have fed Godehute herself, suckling a newborn was, on the whole, not what the medieval woman would do. Adelize may have used a woman in her own household or some other woman from the manor who had recently given birth, the only stipulation in this very personal act would be that the woman’s baby should be the same sex the baby she was feeding. You do have to wonder if mothers of this era bonded with their babies at all. As Godehute grew up no doubt she would become close to her mother who would have acquainted her with all the graces that her position offered, things such as needlework, dancing and singing, if she was lucky she may have also learnt how to manage an estate - these skills would last through her into her adolescence and into womanhood. Godehute certainly would have been typical of a woman of this period, pious, paying strict attention to religious duties and strictly obeying any and all rules of the church which taught the ideal of morality.

Godehute would have had accepted that her husband was already chosen for her, this marriage may well have been arranged while Godehute fed at the breast of the aforementioned wet nurse. The man she would later marry was William Mohun of Dunster in Somerset, her feelings on the subject go unrecorded. William Mohun appears to be have been born around the same time as Godehute, and was probably the second son William Mohun and his wife Agnes de Gant. Mohun received Dunster on the death of his disgraced father between 1143 and 1155, William and Godehute would be the generation that suffered the consequences of those making bad decisions during the time of what history refers to as the Anarchy.

Godehute would have had accepted that her husband was already chosen for her, this marriage may well have been arranged while Godehute fed at the breast of the aforementioned wet nurse. The man she would later marry was William Mohun of Dunster in Somerset, her feelings on the subject go unrecorded. William Mohun appears to be have been born around the same time as Godehute, and was probably the second son William Mohun and his wife Agnes de Gant. Mohun received Dunster on the death of his disgraced father between 1143 and 1155, William and Godehute would be the generation that suffered the consequences of those making bad decisions during the time of what history refers to as the Anarchy.

Godehute grew into womanhood and was married during the aforementioned Anarchy - a power struggle and a time that saw lawlessness sweep across the country that threatened the existence of not only the Tosny’s but the Mohuns too. History dates the Anarchy from the 25th November in 1120 when Godehute was not much more than a toddler and six years before the death of her father Ralph.

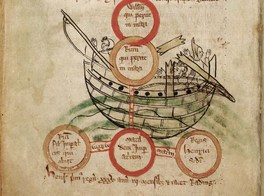

The catalyst for this event in history was the death of William Adelin, King Henry I’s only son who was heir to the English throne. Adelin or Aetheling (an Anglo-Saxon name for one who is expected to take the throne) had perished when the ship in which he was travelling sank in the English Channel. Drowning along with him were the sons and heirs of important men of the realm. One young man who died that day was William Bigod, a kinsman of Godehute’s who was the heir of Roger Bigod of Norfolk and his wife Adalize de Tosny, daughter of Roger de Tosney of Belvoir in Lincolnshire. Adalize and Godehute’s great-grandfathers were probably first cousins. However, I should point out that the exact connection between the Belvior de Tosny’s and the main family line has never been proved conclusively and because of this dates and relationships in the family may differ by at least one generation.

The catalyst for this event in history was the death of William Adelin, King Henry I’s only son who was heir to the English throne. Adelin or Aetheling (an Anglo-Saxon name for one who is expected to take the throne) had perished when the ship in which he was travelling sank in the English Channel. Drowning along with him were the sons and heirs of important men of the realm. One young man who died that day was William Bigod, a kinsman of Godehute’s who was the heir of Roger Bigod of Norfolk and his wife Adalize de Tosny, daughter of Roger de Tosney of Belvoir in Lincolnshire. Adalize and Godehute’s great-grandfathers were probably first cousins. However, I should point out that the exact connection between the Belvior de Tosny’s and the main family line has never been proved conclusively and because of this dates and relationships in the family may differ by at least one generation.

Following the tragedy of the White Ship, Henry I made his daughter Matilda his heir when she married Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou. In support for Matilda, Henry made the leading barons of the realm, including his nephew Stephen of Blois, swear an oath to accept Matilda as his rightful heir, these oaths were taken in in 1127, 1128 and 1131 - the years following Godehute’s father’s death in 1126. The King’s decision was not popular for two reasons, firstly, Matilda was a woman and secondly, Anjou was the sworn enemy of the Normandy. At the same time as Henry had secured Matilda’s inheritance in England for her and her future Angevin offspring he had fortified the area in France known as Argentan, this French commune would prove to be the way into Normandy for Matilda’s husband Geoffrey, whose ‘invasion’ would be aided by disaffected Norman barons who had had their lands confiscated by Henry I. Godehute’s brother Roger de Tosny, was one of these men, he and William, Count of Ponthieu had allied themselves with Geoffrey of Anjou in 1137 the year that both men had been placed under an interdict for ‘acts against the church.’ Roger had been in conflict in Normandy with Waleran and Robert de Beaumont, the twin sons of the Earl of Leicester and also been involved in fighting against Stephen’s older brother Theobald. However, it seems that there was more to this Norman/Angevin alliance than lost landholdings, family feuds and rivalries, this alliance with Anjou was a concerted effort in support of Robert of Gloucester and his support of his half-sister Matilda’s claim to the English throne.

At the time Godehute’s brother Roger de Tosney was allying himself with Geoffrey of Anjou in Normandy, the English barons were rebelling against Stephen. In the west of the country the king was facing a revolt headed by Baldwin de Redvers, the Earl of Devon, Redvers was supported by at least five other West Countrymen, one of them was William Mohun, Godehute’s father in law. By 1139 Stephen had successfully put down the two rebellions in Devon and quickly saw to it that some of these men were punished, he captured the barons strongholds one by one. For his part in these uprisings, William Mohun seemed to have gone unpunished and held onto his castle and lands, although he incurred major disgrace for his actions he kept the title of Earl, which had been conferred on him by Matilda in 1141.

Godehute, as mentioned was born before 1126, however, the date and place of her marriage are not recorded. Helping calculate when it might be is the date of birth of William, Godehute’s firstborn son, he is thought to have been born around 1162. Godehute and William had one daughter named Agnes, she may have been the couples first child which gives a date of marriage to around 1159, that means that William Mohun received Dunster Castle between four and fifteen years after before his marriage. It wouldn’t be the first time that an unmarried noble was head of his household, but fifteen years is a long time and a little bit of a worry. There is no doubt that Godehute, the daughter of Ralph de Tosny had married William Mohun, documents relating to the manor of Bicknoller in Somerset support this fact. Agnes had been given Bicknoller as a marriage parcel when she married William de Windsor, this manor had formed part of the Mohun family estate since the conquest. Agnes held Bicknoller in her own right and on her death in 1236 half of the manor passed to her daughter Godehute - a name used in the Tosny family since c1020 - the Tosny/Mohun match is proved but when it happened will remain elusive.

It is impossible to try to account for those lost years, there can be any number of reasons for the discrepancy, however I think the answer can be found at the turn of the 11th century with the mix up of the parentage (and in which generation they belong) of three Ralph de Tosny’s who were active at that time.

At the time Godehute’s brother Roger de Tosney was allying himself with Geoffrey of Anjou in Normandy, the English barons were rebelling against Stephen. In the west of the country the king was facing a revolt headed by Baldwin de Redvers, the Earl of Devon, Redvers was supported by at least five other West Countrymen, one of them was William Mohun, Godehute’s father in law. By 1139 Stephen had successfully put down the two rebellions in Devon and quickly saw to it that some of these men were punished, he captured the barons strongholds one by one. For his part in these uprisings, William Mohun seemed to have gone unpunished and held onto his castle and lands, although he incurred major disgrace for his actions he kept the title of Earl, which had been conferred on him by Matilda in 1141.

Godehute, as mentioned was born before 1126, however, the date and place of her marriage are not recorded. Helping calculate when it might be is the date of birth of William, Godehute’s firstborn son, he is thought to have been born around 1162. Godehute and William had one daughter named Agnes, she may have been the couples first child which gives a date of marriage to around 1159, that means that William Mohun received Dunster Castle between four and fifteen years after before his marriage. It wouldn’t be the first time that an unmarried noble was head of his household, but fifteen years is a long time and a little bit of a worry. There is no doubt that Godehute, the daughter of Ralph de Tosny had married William Mohun, documents relating to the manor of Bicknoller in Somerset support this fact. Agnes had been given Bicknoller as a marriage parcel when she married William de Windsor, this manor had formed part of the Mohun family estate since the conquest. Agnes held Bicknoller in her own right and on her death in 1236 half of the manor passed to her daughter Godehute - a name used in the Tosny family since c1020 - the Tosny/Mohun match is proved but when it happened will remain elusive.

It is impossible to try to account for those lost years, there can be any number of reasons for the discrepancy, however I think the answer can be found at the turn of the 11th century with the mix up of the parentage (and in which generation they belong) of three Ralph de Tosny’s who were active at that time.

As well as the date of Godehute’s marriage I cannot pinpoint where she resided in the months following her wedding, however, the Mohun families fall from grace may go some way to answering that question. Either by choice or design, William and Godehute seemed to have spent their lives out of the limelight as there is no evidence of William taking part in local government and it seems that he also let parts of his manor at Dunster fall into disrepair, this suggests that he and Gotehute lived quietly at Dunster struggling with the management of the estate or they abandoned the castle altogether.

Godehute’s marriage to William Mohun lasted less than fifteen years. William’s death left Godehute a widow with six children under the age of fourteen, they were the aforementioned William and Agnes plus Geoffrey, John and Thomas. With an underage heir, the Mohun family estates were taken by the crown and William became a ward of Henry II. The king appointed the Bishop of Winchester to look after and to administer the Mohun estates and allowed 18 shillings for William’s maintenance. There is little information regarding Godehute at this time, but we do know that the estate was bringing in little in the way of money. Tolls on the land were not what was expected, and the mills were also showing a decline in revenue, however, records show that the crown was receiving a large sum of money from the sale of corn and wine that was produced on other of the Mohun estates.

Godehute lived through the last years of Henry II’s reign, she had witnessed her father in law die in obscurity, a direct result of the loss of 104 of his knights to his neighbour Henry de Tracy in 1142. As Mohun’s disgrace left Godehute’s generation to suffer the consequences of his actions the De Tracy family were, for a generation at least, rising stars, but like the Mohuns the de Tracys eventually would fall out of royal favour too. Incidentally, in 1170 it was a de Tracy who was one of the four men who had heard Henry II’s outburst "Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?’ and then had gone on to murder Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. On hearing this news you have to wonder if William and Godehute have gloated over it. The last years of Henry II's reign were fraught, his sons had mistrusted each other and disputes between them flared up. By 1186 Henry had fallen out the new French king Philip Augustus following the death of Henry’s son Geoffrey which in turn altered the balance of power between Richard and John. Godehute de Tosny did not live to hear about the news that John had finally turned against his father, an act that is thought to have hastened the king's death in the July of 1189.

We will have to assume that Godehute lived out her widowhood at Dunster, I have found no official documents on which she signed her name and she witnessed no charters. However, this doesn't mean that she did not put her name to any documents because women of the lesser nobility, like Godehute, were just as likely to have done so as those in the higher echelons of society. However, just as the one manor Godehute de Tosny brought to her marriage became a forgotten part of a larger estate, Godehute too faded into obscurity after her husband's death. Godehute was not granted the title of Countess of Somerset because if she did we may have heard a little more about her. Sadly though Godehute was a victim of her father in laws actions and because of this we will never know the real Godehute, we can only guess how she managed her life and coped with what it threw at her. Godehute’s life, like many medieval women, is viewed by the gender-based functions she performed - that is a wife, a mother, a widow and sometimes an heiress. Godehute de Tosny was all of these things.

Godehute lived through the last years of Henry II’s reign, she had witnessed her father in law die in obscurity, a direct result of the loss of 104 of his knights to his neighbour Henry de Tracy in 1142. As Mohun’s disgrace left Godehute’s generation to suffer the consequences of his actions the De Tracy family were, for a generation at least, rising stars, but like the Mohuns the de Tracys eventually would fall out of royal favour too. Incidentally, in 1170 it was a de Tracy who was one of the four men who had heard Henry II’s outburst "Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?’ and then had gone on to murder Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. On hearing this news you have to wonder if William and Godehute have gloated over it. The last years of Henry II's reign were fraught, his sons had mistrusted each other and disputes between them flared up. By 1186 Henry had fallen out the new French king Philip Augustus following the death of Henry’s son Geoffrey which in turn altered the balance of power between Richard and John. Godehute de Tosny did not live to hear about the news that John had finally turned against his father, an act that is thought to have hastened the king's death in the July of 1189.

We will have to assume that Godehute lived out her widowhood at Dunster, I have found no official documents on which she signed her name and she witnessed no charters. However, this doesn't mean that she did not put her name to any documents because women of the lesser nobility, like Godehute, were just as likely to have done so as those in the higher echelons of society. However, just as the one manor Godehute de Tosny brought to her marriage became a forgotten part of a larger estate, Godehute too faded into obscurity after her husband's death. Godehute was not granted the title of Countess of Somerset because if she did we may have heard a little more about her. Sadly though Godehute was a victim of her father in laws actions and because of this we will never know the real Godehute, we can only guess how she managed her life and coped with what it threw at her. Godehute’s life, like many medieval women, is viewed by the gender-based functions she performed - that is a wife, a mother, a widow and sometimes an heiress. Godehute de Tosny was all of these things.

Godehute outlived her husband by at least ten years, she is thought to have died in 1186. It is likely that she was buried at Bruton in the Priory that was founded by her father in law in 1142. As I mentioned earlier I found her name on no documents during her lifetime, however in death at least we finally get to see a tiny glimpse of her. Her son William, before he left on a pilgrimage had asked of the canons of the priory that on every anniversary of his death candles should be lit in his honour, and prayers should be offered for the soul of his mother Godehute - interestingly not his father.

With Godehute’s death, my Tosny family line ended but it's bloodline continued through her Mohun offspring, namely her great-granddaughter Alice Mohun and then through the Beauchamp family of Hatch in Somerset. The main Mohun family line at Dunster Castle, however, continued through father to son for three more generations and ended in the fourteenth century when the last male Mohun died without issue. But what of the Tosny family?

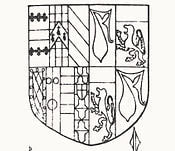

This ancient Norman family, whose roots are embedded, in part, in the cold regions of Scandinavia and who played their part in the formation of Normandy managed to keep their head above water until the end of the 13th century when one Robert de Tosny died leaving as his heir, his sister Alice. Alice was the widow of Thomas Leybourne and until her marriage in 1309 to Guy de Beauchamp, the Earl of Warwick, she held the Tosny lands herself. After that, the lands became part of the Beauchamp estates as you can see from the Beauchamp coat of arms in which the Tosny heraldic icon, the maunch gules or a red sleeve, is quartered and can be seen on the top half of their shield, second from the right at the top and last on the right at the bottom

With Godehute’s death, my Tosny family line ended but it's bloodline continued through her Mohun offspring, namely her great-granddaughter Alice Mohun and then through the Beauchamp family of Hatch in Somerset. The main Mohun family line at Dunster Castle, however, continued through father to son for three more generations and ended in the fourteenth century when the last male Mohun died without issue. But what of the Tosny family?

This ancient Norman family, whose roots are embedded, in part, in the cold regions of Scandinavia and who played their part in the formation of Normandy managed to keep their head above water until the end of the 13th century when one Robert de Tosny died leaving as his heir, his sister Alice. Alice was the widow of Thomas Leybourne and until her marriage in 1309 to Guy de Beauchamp, the Earl of Warwick, she held the Tosny lands herself. After that, the lands became part of the Beauchamp estates as you can see from the Beauchamp coat of arms in which the Tosny heraldic icon, the maunch gules or a red sleeve, is quartered and can be seen on the top half of their shield, second from the right at the top and last on the right at the bottom

You can read Godehute’s and my family story here

meanderingthroughtime.weebly.com/william---1193.html

meanderingthroughtime.weebly.com/william---1193.html