|

Changing

Allegiances |

Thomas Vaughan was still allied with Jasper Tudor during the first months of 1459, on the 21st of April Vaughan stood as guarantor for Tudor and this may have been in connection with properties, such as Llangoed that Tudor received that same day. Between the end of April and the beginning of July, Vaughan had switched allegiances. Historians differ in their view of whether he was at Ludford Bridge, but he was certainly attained at the Coventry Parliament, charged with imagining and compassing the death of the king on the 4th July 1459.

And forasmoch as Aleyse the wyf of the seid Richard erle of Salesbury, the first day of August, the yere of youre moost noble reigne .xxxvij. th , at Middelham in youre shire of York, and William Oldhall knyght, and Thomas Vaghan late of London squier, at London, in the parissh of Seint Jame at Garlikhithe, in the warde of Quenehithe, the fourth day of Jule, the same yere, falsely and traiterously ymagyned and compassed the deth and fynall destruccion of you, soverayne lord; and in accomplisshment and executyng therof, the seid Aleise, at Middelham aforeseid the seid first day of August, and the seid William Oldhall and Thomas Vaghan, at London, in the seid parissh and warde, the seid fourth day of Jule,[col. b] traiterously labored, abetted, procured, stered and provoked the seid duc of York, and the seid erles of Warrewyk and Salesbury, to doo the seid tresons, rebellions, gaderynges, ridynges and reryng of werre ayenst youre moost roiall persone, at the seid toune of Blore and Ludeford: to ordeyne and establissh, by the seid auctorite, that the same Aleise, William Oldhall and Thomas Vaghan for the same be reputed, taken, demed, adjugged and atteinted of high treson.

J G Bellamy in his The Laws of Treason in England in the Later Middle Ages suggests that discussions where held, that day in July, at Vaughan's home of Garlek House in London, but the wording of the attainder states that they were at Middleham, the home of the Alice Montacute, Countess of Salisbury. At the meeting, along with the Vaughan and the Countess was William Oldhall. Oldhall was years older than Vaughan and a staunch adherent to the House of York, in 1415 he had been an esquire in the service of Thomas Beaufort, great uncle to Edmund Beaufort and with Beaufort at Harfleur. It is not beyond the realms of possibility that Vaughan knew Oldhall via his association with the Beauforts and it was he whose words may have finally convinced Vaughan that abandoning the Lancastrian for the Yorkist cause was the best way forward.

After Ludford, the Countess of Salisbury hot-footed it to Ireland, William Oldhall and as previously mentioned, Thomas Vaughan headed to Calais. He was a condemned traitor, and a sentence of death, like the Sword of Damocles, was hanging over his head. No doubt the forfeiture of his property was the last thing on his mind, however, putting as many miles between him and Henry’s forces was. But as he sailed on the choppy autumn seas between England and Calais, he need not have worried, the Bill of Attainder would have little effect on those concerned as it was reversed by the Parliament in London in the October of the following year. Before that, in January, Richard Woodville and his son Anthony, who would be executed along with Vaughan in 1483 were captured, the Earl of March had a fine time poking fun at Woodville regarding his marriage to Jacquetta, you have to wonder if this incident was ever brought up when the couple became his father and mother in law. In May, Warwick sailed for Ireland to discuss tactics with the Duke of York and returning he brought his mother, Vaughan’s co-conspirator with him.

A month later, Warwick arrived back in England making his way to Sandwich in Kent, after taking the town he and his forces headed for London but found that his way into the city was barred, but upon arrival, the populace had changed its mind and London's gates were thrown open. Matthew Lewis in his book, The Wars of the Roses: Key Players in the Struggle for Supremacy suggests part of the reason the inhabitants of London were thinking differently was that Warwick liked to spend money, as did the Earl of March.

“Edward owed fortunes to the merchants all over London, these men would never see their bills paid and might be ruined, and if he was resisted, why then would he replay those men who had abandoned him?”

The above statement Matthew applies to Edward in 1471, but it gives us a good idea of how people were thinking at the time.

In charge in London were Lancastrian, Thomas, Lords Scales and Robert, Lord Hungerford, their remit was to defend London Bridge but they were forced back into the Tower of London where Neville and his forces laid siege. The events of the 2nd to the 19th of July at the Tower of London would see the beginning of another new stage in the life of Thomas Vaughan and the events that followed the Yorkist success at Northampton on the 10th of July would the beginning of a change for the country.

After Ludford, the Countess of Salisbury hot-footed it to Ireland, William Oldhall and as previously mentioned, Thomas Vaughan headed to Calais. He was a condemned traitor, and a sentence of death, like the Sword of Damocles, was hanging over his head. No doubt the forfeiture of his property was the last thing on his mind, however, putting as many miles between him and Henry’s forces was. But as he sailed on the choppy autumn seas between England and Calais, he need not have worried, the Bill of Attainder would have little effect on those concerned as it was reversed by the Parliament in London in the October of the following year. Before that, in January, Richard Woodville and his son Anthony, who would be executed along with Vaughan in 1483 were captured, the Earl of March had a fine time poking fun at Woodville regarding his marriage to Jacquetta, you have to wonder if this incident was ever brought up when the couple became his father and mother in law. In May, Warwick sailed for Ireland to discuss tactics with the Duke of York and returning he brought his mother, Vaughan’s co-conspirator with him.

A month later, Warwick arrived back in England making his way to Sandwich in Kent, after taking the town he and his forces headed for London but found that his way into the city was barred, but upon arrival, the populace had changed its mind and London's gates were thrown open. Matthew Lewis in his book, The Wars of the Roses: Key Players in the Struggle for Supremacy suggests part of the reason the inhabitants of London were thinking differently was that Warwick liked to spend money, as did the Earl of March.

“Edward owed fortunes to the merchants all over London, these men would never see their bills paid and might be ruined, and if he was resisted, why then would he replay those men who had abandoned him?”

The above statement Matthew applies to Edward in 1471, but it gives us a good idea of how people were thinking at the time.

In charge in London were Lancastrian, Thomas, Lords Scales and Robert, Lord Hungerford, their remit was to defend London Bridge but they were forced back into the Tower of London where Neville and his forces laid siege. The events of the 2nd to the 19th of July at the Tower of London would see the beginning of another new stage in the life of Thomas Vaughan and the events that followed the Yorkist success at Northampton on the 10th of July would the beginning of a change for the country.

On the 2nd of July, the Siege of the Tower of London began, a few days later Richard Neville, his brother Lord Fauconberg and Edward, plus the main force of the Yorkist army were making their way to do battle at Northampton, leaving a smaller force to continue the siege. Lords Scales and Lord Hungerford had been bombarding the city, where it has been said, many of London’s residents were killed. Among others trapped in the Tower were Henry’s Treasurer Thomas Browne, the son of a wealthy city merchant who had made an advantageous marriage to the great-great granddaughter of Richard Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel and Surrey, Browne was also a wealthy landowner and a man of note in Kent.

A seventeen-day siege ensued ending with the death of Lord Scales, and the execution on charges of treason of Thomas Browne.

After the Battle of Northampton, Henry VI once again found himself a prisoner and on his way to London, this was followed by the Duke of York’s return to England. Arriving in England on the 9th September he headed for London to make his play for the crown.

The Parliamentary Roll following Northampton makes interesting reading, it goes some way to help us understand of the tension of the times. Parliament itself was summoned by writ on the 30th of July and opened in the king's presence at Westminster on the 7th October, the Duke of York did not attend. However he did enter the parliamentary chamber at 10 o’clock three days later and found the king and the commons were not sitting. We are told that the Duke of York made an ‘arrogant advance’ upon the throne and stated that ‘he purposed nat to ley daune his swerde but to challenge his right'. Much is made of this scene in history, although it goes unmentioned in the roll. No one spoke, only listened, and those who did listen were soon running back to their lords telling of the great silence that engulfed the chamber and how the Archbishop of Canterbury had asked York if he wanted to see the king. Historians all agree that this was a bad move on York's part and that he had totally misjudged the situation, the consensus of opinion was that Henry was not the king he should have been, but he was still king.

Six days later York pursued his claim along the correct channels.

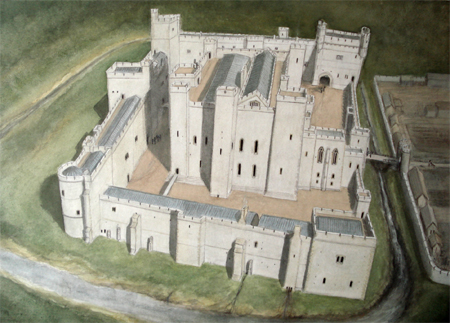

Eventually, after much discussion and in an effort to get the situation under some sort of control the Act of Accord was signed on the 25th of October 1460. This acknowledged the Duke of York as the heir to Henry VI and effectively disinherited his son Edward. It was hoped that this agreement would put an end to the political tension that had caused so much trouble in previous years, but it was not to be. The Act of Accord naturally left the Lancastrians foaming at the mouth, many were angry that the act had swept the rules of primogeniture under the carpet, a rule that had protected the rights of the noble family for decades, without which there would be chaos. Many Lancastrians, with the support of their Welsh allies, rallied to the cause resulting in a number of revolts occurring in the country with Henry VI’s queen, Margaret of Anjou, at its helm. The first serious clash happened in Yorkshire, just over two months after the Act of Accord was signed, as Margaret had headed to Wales, Richard, Duke of York, now heir apparent made his way towards Sandal Castle to meet the forces of the opposing army.

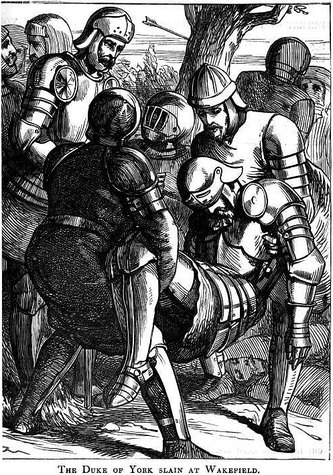

It was here at the Battle of Wakefield in the December of 1460 that the Duke of York met his end.

A seventeen-day siege ensued ending with the death of Lord Scales, and the execution on charges of treason of Thomas Browne.

After the Battle of Northampton, Henry VI once again found himself a prisoner and on his way to London, this was followed by the Duke of York’s return to England. Arriving in England on the 9th September he headed for London to make his play for the crown.

The Parliamentary Roll following Northampton makes interesting reading, it goes some way to help us understand of the tension of the times. Parliament itself was summoned by writ on the 30th of July and opened in the king's presence at Westminster on the 7th October, the Duke of York did not attend. However he did enter the parliamentary chamber at 10 o’clock three days later and found the king and the commons were not sitting. We are told that the Duke of York made an ‘arrogant advance’ upon the throne and stated that ‘he purposed nat to ley daune his swerde but to challenge his right'. Much is made of this scene in history, although it goes unmentioned in the roll. No one spoke, only listened, and those who did listen were soon running back to their lords telling of the great silence that engulfed the chamber and how the Archbishop of Canterbury had asked York if he wanted to see the king. Historians all agree that this was a bad move on York's part and that he had totally misjudged the situation, the consensus of opinion was that Henry was not the king he should have been, but he was still king.

Six days later York pursued his claim along the correct channels.

Eventually, after much discussion and in an effort to get the situation under some sort of control the Act of Accord was signed on the 25th of October 1460. This acknowledged the Duke of York as the heir to Henry VI and effectively disinherited his son Edward. It was hoped that this agreement would put an end to the political tension that had caused so much trouble in previous years, but it was not to be. The Act of Accord naturally left the Lancastrians foaming at the mouth, many were angry that the act had swept the rules of primogeniture under the carpet, a rule that had protected the rights of the noble family for decades, without which there would be chaos. Many Lancastrians, with the support of their Welsh allies, rallied to the cause resulting in a number of revolts occurring in the country with Henry VI’s queen, Margaret of Anjou, at its helm. The first serious clash happened in Yorkshire, just over two months after the Act of Accord was signed, as Margaret had headed to Wales, Richard, Duke of York, now heir apparent made his way towards Sandal Castle to meet the forces of the opposing army.

It was here at the Battle of Wakefield in the December of 1460 that the Duke of York met his end.