|

Samuel Purches 5th Great Grandfather

1733 - 1804 |

The county of Hampshire is long associated with King Alfred, whose Kingdom of Wessex had at its centre the city of Winchester. It is also associated with the Normans, invaders who destroyed villages to make way for their New Forest so their newly crowned kings could hunt. From the time of the Anarchy, Hampshire suffered from the fallout of battles and skirmishes, and towns like Winchester and Andover had to rebuild during Matilda and Stephen of Blois’s fight for the crown. Famine, closely followed by the Black Death hit the county, and trade suffered during the Hundred Years War when Hampshire’s coastline was subject to attack from the French. The Wars of the Roses hardly touched the county, but one important event during this period, the marriage of Henry VI to Margaret of Anjou took place at Titchfield Abbey. The Tudor period saw the building of Henry VII’s dry dock in Portsmouth and later it would become the home of England's famous naval fleet.

Portsea itself developed from salt marsh islands, tributary rivers, and over the centuries tidal erosion. Rising seas and later reclamation changed Portsea into the shape we see today. As an island it is separated from the mainland by a tidal waterway known as Portbridge Creek, the toing and froing of the native population was probably by boat until the 12th century when the first recorded mention of a bridge can be found. In the time before the conquest of England Portsea had three manors. These manors, Fratton, Copnor, and Buckland were held by King Edward, Earl Godwin, and Huge de Port respectively. By the time of the Domesday Survey in 1086, there were thirty-one families living on the island. Buckland is where the first church built on the island, that of St Marys, was founded. In 1066, Buckland was held by Alward from Earl Godwin and consisted of six villagers, two smallholders and two slaves with enough ploughland to accommodate four plough teams. By 1086, along with Copnor to the west, Buckland was held by Heldred from Hugh de Port, a Norman knight in the service of Odo, Bishop of Bayeux. Hugh de Port died as a monk at Winchester, however, later generations of the Port family can be found associated with Southampton and Portchester.

By the end of the 9th century, the Saxons and the Danes had gone, and in 1055 King Harold had set off from the island with his fleet of seven hundred ships in a failed attempt to see off the Normans. Over the next forty years, members of William the Conqueror's immediate family landed at, and set off from, the island to stake their particular claim to the English throne. Nearly one hundred years later, another Norman, Baldwin de Portsea appears to be the next important person in the ancient history of the island; it is he who is responsible for the founding of St Mary's on the site where the present church stands.

By the end of the 9th century, the Saxons and the Danes had gone, and in 1055 King Harold had set off from the island with his fleet of seven hundred ships in a failed attempt to see off the Normans. Over the next forty years, members of William the Conqueror's immediate family landed at, and set off from, the island to stake their particular claim to the English throne. Nearly one hundred years later, another Norman, Baldwin de Portsea appears to be the next important person in the ancient history of the island; it is he who is responsible for the founding of St Mary's on the site where the present church stands.

This small rural area stood still for many centuries, its few inhabitants watching as Portsmouth, a neighbouring community, outgrew it. A chapel was built in Portsmouth as a dependency of St. Mary’s and was dedicated to St. Thomas by Jean of Gisors of Normandy who had, as mentioned previously, purchased lands in Portsmouth. Gisors donated some of this land in order that this chapel could be built - "to the glorious honour of the martyr Thomas of Canterbury, one time Archbishop, on (my) land which is called Sudewede, the island of Portsea.” Thomas Becket is known to have spent time during his ‘exile’ at Gisors and may have known Jean of Gisor personally. On Becket's return to England, he was brutally murdered in Canterbury Cathedral in December 1170. Some six centuries later St Thomas's became the Cathedral Church of St Thomas of Canterbury.

Baldwin de Portsea’s chapel of St Mary also began as a small chapel, it is mentioned as early as 1164, when he gave it, along with some land, cattle, sheep, and hogs to the prior and canons of Southwick Priory on the mainland. By the 14th century, the chapel would become a parish church, and by the time Henry VIII was on England's throne St Mary’s is documented as having a tower, however, the building would stay relatively unchanged and at the heart of the rural community for nearly seven hundred years.

By the mid-18th century, Portsea was referred to as Portsmouth Common and was described by one writer as ‘a barren, desolate heath’ however, it was in this community at its ancient church, the oldest on the island of Portsea, that Samuel Purches was married in 1755.

By the mid-18th century, Portsea was referred to as Portsmouth Common and was described by one writer as ‘a barren, desolate heath’ however, it was in this community at its ancient church, the oldest on the island of Portsea, that Samuel Purches was married in 1755.

The following eighty years saw St Mary’s become unsuitable for the use of a growing community. It was demolished in 1843 and replaced. A new church incorporated the aforementioned Tudor tower and was similar in design to that of fenland churches in the east of the country. This second church lasted only forty-four years being too damp and dark. A third and final church dedicated to St Mary was opened in 1889, its Tudor tower can still be seen from a distance, but it no longer dominates the area; it is the Royal Naval base that now has that honour.

The lanes that crisscrossed Portsea’s ancient fields, the ones on which Samuel and Elizabeth walked home as a married couple are now a rarity, what green space there is, is limited to a band that runs along the shoreline.

The earliest reference to the surname of Purches in Portsea is in 1712 followed by another in 1748. Until the marriage of Samuel to Elizabeth Davis on the 26th December 1755, there is no mention of any persons with this surname, after that, they are few and far between and those I found are not, it seems, connected to one another. It is only in 1841 that a connection between a number of Purches families can be proved, all members of these families were all born and bred in Portsea, they are, bar one, members of the same family.

So where was Samuel Purches born and where did his ancestors live before 1755?

The lanes that crisscrossed Portsea’s ancient fields, the ones on which Samuel and Elizabeth walked home as a married couple are now a rarity, what green space there is, is limited to a band that runs along the shoreline.

The earliest reference to the surname of Purches in Portsea is in 1712 followed by another in 1748. Until the marriage of Samuel to Elizabeth Davis on the 26th December 1755, there is no mention of any persons with this surname, after that, they are few and far between and those I found are not, it seems, connected to one another. It is only in 1841 that a connection between a number of Purches families can be proved, all members of these families were all born and bred in Portsea, they are, bar one, members of the same family.

So where was Samuel Purches born and where did his ancestors live before 1755?

The answer to that question is I don’t know. They may have always lived on the island, but it is more than likely that they arrived from the mainland in the early years of the 18th century when there was a mass influx of people. The surname of Purches is, of sorts, linked to an occupation, it is unlikely that early families in other counties were related, however, despite the odd Purches found elsewhere in the country, the vast majority of people with this surname are Hampshire born. Therefore, Samuel was probably born on the mainland about 1733 and came to Portsea accompanied by his parents or moved to the island as an adult, tempted by what Portsmouth had to offer.

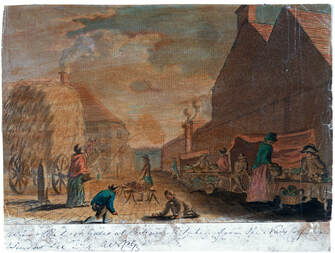

The eighteenth century, the time when Samuel made his home in Portsea, saw the end of the Stuart period and the beginning of the Georgian age, it was an age of expansion, an age of inventions that brought changes to the textile and mining industry, it also brought changes in agriculture. It was at this time that the country maintained a relatively large Royal Navy, and in Portsea, and ports all over the country, the demand for war supplies stimulated growth in the industrial sector, particularly naval supplies, and munitions. It also brought with it a demand for people to work in other occupations associated with the ports - from dockyard workers to shipwrights, from blacksmiths to farriers, shopkeepers to innkeepers, and this, in turn, resulted in the migration of people from rural areas into towns where there were jobs by the dozen. It is highly likely that these were the reasons Samuel Purches was in Portsea, but what he was actually doing there is lost to history. Also lost to history is when, where and how he met Elizabeth Davis. Again it is probable that they met in either Portsea or Portsmouth itself as there are a number of families with the surname of Davis.

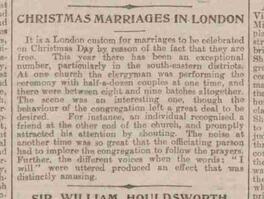

So, there they were, on the day after Christmas 1755, standing saying their I do’s at the altar of St Mary’s Church. A hint that Samuel was actually employed at this time lies in the day of the marriage, the day we celebrate as Boxing Day. It was not uncommon to be married on either Christmas Day or Boxing Day in the 18th century as these were days when working people were not expected to work. Christmas Day and Boxing Day were traditional holidays. In London for instance, it is documented that one clergyman was conducting eight weddings at one time

So, there they were, on the day after Christmas 1755, standing saying their I do’s at the altar of St Mary’s Church. A hint that Samuel was actually employed at this time lies in the day of the marriage, the day we celebrate as Boxing Day. It was not uncommon to be married on either Christmas Day or Boxing Day in the 18th century as these were days when working people were not expected to work. Christmas Day and Boxing Day were traditional holidays. In London for instance, it is documented that one clergyman was conducting eight weddings at one time

Marriages in the 18th century took place between those of the same social class. In this period the average age, a marriage took place was the mid-twenties, males were normally older, about twenty-six, and women were slightly younger. Interestingly, marriages lasted, on average, seventeen years and ended with the death of one partner. Samuel and Elizabeth would fit nicely into this category, however, their marriage lasted nearly fifty years and ended with Samuels's death in 1804. This longevity and the lack of children is a worry and suggests that maybe Samuel and Elizabeth were not my 5th great grandparents but my 6th, and therefore not the parents of Samuel Purches, my 4th great grandfather, however, the lack of Purches’s on the island and the fact that Samuel and Elizabeth is a name used over and over again makes it possible.

Samuel and Elizabeth's first child did not arrive until March 1757, this baby was a girl. She was given the name of Elizabeth and baptised a few days later at St Mary’s in its rather plain 14th-century font. Three more children were born over the following thirteen years, Sarah was born in 1763, Samuel in 1766, and Ann in 1770 all three were baptised within a few days of their birth as was the custom at the time, only Samuel was baptised at the aforementioned St Thomas, Portsmouth’s cathedral church. The baptism of Samuel in a different church is odd too and adds weight to my lost generation theory, but it may simply be due to where the family lived at the time. Four children in fifteen years would be classed as a small family, but it is not unusual, the dates between the births suggest that Samuel and Elizabeth lost children either at birth or in early infancy. However, the absence of the birth of more children may not be due to tragedy at all, in fact, it may be that Samuel was simply not there, the irregularity in the dates birth of children in the following three generations is accounted for by the Purches men being ‘away at sea.’

Samuel and Elizabeth's first child did not arrive until March 1757, this baby was a girl. She was given the name of Elizabeth and baptised a few days later at St Mary’s in its rather plain 14th-century font. Three more children were born over the following thirteen years, Sarah was born in 1763, Samuel in 1766, and Ann in 1770 all three were baptised within a few days of their birth as was the custom at the time, only Samuel was baptised at the aforementioned St Thomas, Portsmouth’s cathedral church. The baptism of Samuel in a different church is odd too and adds weight to my lost generation theory, but it may simply be due to where the family lived at the time. Four children in fifteen years would be classed as a small family, but it is not unusual, the dates between the births suggest that Samuel and Elizabeth lost children either at birth or in early infancy. However, the absence of the birth of more children may not be due to tragedy at all, in fact, it may be that Samuel was simply not there, the irregularity in the dates birth of children in the following three generations is accounted for by the Purches men being ‘away at sea.’

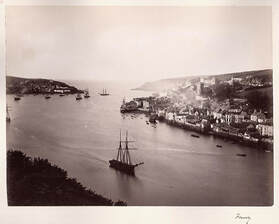

You can see Portsmouth Harbour, as Samuel and Elizabeth would have seen it in Dominic Serres's painting of an English ship shortening its sail as it enters the harbour, add to this a description of the naval security at the harbour in 1721 by Daniel Defoe and you can get a feel what life was like for Samuel and Elizabeth.

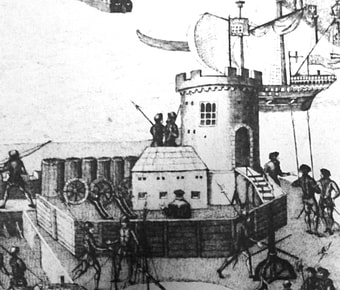

'The situation of this place is such, that it is chosen, as may well be said, for the best security to the navy above all the places in Britain; the entrance into the harbour is safe, but very narrow, guarded on both sides by terrible platforms of cannon, particularly on the Point; which is a suburb of Portsmouth properly so call’d, where there is a brick platform built with two tire of guns, one over another, and which can fire so in cover, that the gunners cannot be beaten from their guns, or their guns easily dismounted; the other is from the point of land on the side of Gosport, which they call Gilkicker, where also they have two batteries.

Before any ships attempt to enter this port by sea, they must also pass the cannon of the main platform of the garrison, and also another at South-Sea-Castle; so that it is next to impossible that any ships could match the force of all those cannon, and be able to force their way into the harbour; in which I speak the judgment of men well acquainted with such matters, as well as my own opinion, and of men whose opinion leads them to think the best of the force of naval batteries too...'

There is nothing to find in Samuel and Elizabeth’s life together, their story is told through the events they may have witnessed and the changes to the island they called home. Samuel would live to see the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars but not the English victory at Trafalgar; he was dead by the end of March 1804 and buried on the 28th March, probably in the graveyard of St Marys. After Samuel’s death, Elizabeth left Portsea for Gosport, a market town just over the water that supplied Portsea with food and beer, and other consumables, it was also notorious for its press gangs. Elizabeth survived Samuel by two years, she died in 1806 and is buried in the cemetery of Holy Trinity Church.

'The situation of this place is such, that it is chosen, as may well be said, for the best security to the navy above all the places in Britain; the entrance into the harbour is safe, but very narrow, guarded on both sides by terrible platforms of cannon, particularly on the Point; which is a suburb of Portsmouth properly so call’d, where there is a brick platform built with two tire of guns, one over another, and which can fire so in cover, that the gunners cannot be beaten from their guns, or their guns easily dismounted; the other is from the point of land on the side of Gosport, which they call Gilkicker, where also they have two batteries.

Before any ships attempt to enter this port by sea, they must also pass the cannon of the main platform of the garrison, and also another at South-Sea-Castle; so that it is next to impossible that any ships could match the force of all those cannon, and be able to force their way into the harbour; in which I speak the judgment of men well acquainted with such matters, as well as my own opinion, and of men whose opinion leads them to think the best of the force of naval batteries too...'

There is nothing to find in Samuel and Elizabeth’s life together, their story is told through the events they may have witnessed and the changes to the island they called home. Samuel would live to see the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars but not the English victory at Trafalgar; he was dead by the end of March 1804 and buried on the 28th March, probably in the graveyard of St Marys. After Samuel’s death, Elizabeth left Portsea for Gosport, a market town just over the water that supplied Portsea with food and beer, and other consumables, it was also notorious for its press gangs. Elizabeth survived Samuel by two years, she died in 1806 and is buried in the cemetery of Holy Trinity Church.

The average age of life expectancy in the 1700s was thirty-seven years, it rose to forty-one by 1820, going by these figures both William and Elizabeth Purches lived to a very good age being in their late sixties or seventies when they died. Although this is not impossible, I have to admit to being a little bit concerned that I may have missed a generation, but as mentioned previously, all Purches mentioned in censuses have been accounted as being members of the same family, therefore I will have to stick to my findings that they were my 5th great grandparents.