|

Henry James Purches

1837 - 1913 |

The Purches family's roots lay in the County of Hampshire, however, from the early 18th century they could be found in the rural community at the centre of the island that is now called Portsea. Three generations of Henry’s ancestors were born on the island including his father William Samuel, he would be the first to leave. Henry James Purches would be the first of his family to be born in Cornwall.

Henry's father had arrived in Par in 1837 following a transfer from his position as a coastguard in the Norfolk village of Burnham Overy. This move came at a time when smuggling was in decline, and it meant that there was a change in what William Samuel was expected to do. His role was less about apprehending the smuggler and more about wrecks, salvage, and lifesaving, he was therefore employed to watch over shipping coming in and out of Par’s tiny harbour. It was at the time of Henry’s birth that the harbour was being expanded to cope with the increased amount of shipping that served the copper and china clay mines that were owned by industrialist Joseph Treffry. The last improvement made by Treffry was an extension to the railway along the canal bank to the harbour, this was completed when Henry had entered his teens. The opening of the Cornwall Railway from Plymouth in 1859 encouraged further expansion of Par north-eastwards towards the village of Tywardreath.

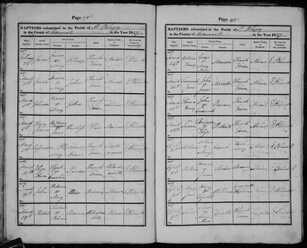

Henry James Purches was born to William Samuel Purches and his wife Jane Pentreath on the 14th of February 1837. Despite the Registration Act coming into force on the 18th August the previous year, Henry’s birth is not officially recorded as it was not until a year later that registrations actually took place. Henry first appears in official records on the 5th March 1837 when his name can be found in the register of the 15th-century church of St Blaise. Par had no church of its own so children were welcomed into the church in St Blazey, a village just a few miles north-west of Par. In the 1841 census, Henry was four-year-old and was living with his father and his siblings, his mother Jane was absent, she had returned home to the fishing village of Paul, to tend to her ailing mother. Ten years later Henry was fourteen and is listed as being a scholar. Par was a ‘new’ village and it would grow to accommodate mining families who had moved to the area, yet there was no school building in which to educate the children. The nearest school was on Church Street in the aforementioned village of Twardreath and was situated just to the east of Treffrey’s new railway line, it was this school Henry attended. At the beginning of the 19th century, educating children was not seen as beneficial, some saw schooling for the working classes as unnecessary or even dangerous, but there were those who were asking how teachers could effectively teach geography, history, and science to those who could not read. By the time Henry began his school career the risks of educating the working classes were generally seen as outweighing the risks of leaving children ignorant. However, in the 1850s, around half of the children in England and Wales were not in school during the working week, Henry, I like to think was not one of them. At school, Henry would have been taught three basic educational skills - reading, writing and arithmetic, commonly known as the three R’s. In the last year of Henry’s education, the family had moved from Par to the tiny fishing village of Polkerris, there was no school there either, therefore it was likely that Henry and his younger sister Emma would continue to attend Twardreath School. How Henry got on with his lessons goes unrecorded, however by the end of the summer of 1851, his time in formal education would have come to an end and he was probably wondering where life would take him, like his ancestors he didn't have much of a choice, the sea was in his blood.

Henry was still just a boy, too young to be heading out into the vast oceans you would think, but boys were a familiar sight on board British ships in the 19th century. The Merchant Navy, like the Royal Navy, had been experiencing issues with the uptake of men capable of coping with the physical tasks they were expected to perform, without healthy men on board ships both the defence and trade would suffer. Training schemes were implemented designed to create fitness and health among those wishing to take to the sea, so much so that the size and the strength of a boy became important. In 1851 for instance, a fourteen-year-old needed to be 4ft 8in to gain a position in the navy, he needed to be of good weight too.

Henry, at his full adult height, was only 5ft 4in, I imagine then that he would have been under the expected height to join the Royal Navy, if the merchant navy were adopting the same practices then it is likely that he may have been rejected by the merchant navy too. Henry, it appears, was short in stature and may have appeared physically weak, until he bulked up there may have been no chance, under the new rules that he could go to sea. I wonder though, in reality, were these rules actually applied? If they were, it may account for the five-year gap between Henry leaving school and the first time he is recorded on board ship. Henry’s service record shows that the first time he went to sea as an Able Seaman was on the 2nd September 1856 where his duties concerned the operation and upkeep of deck department areas and equipment. To take up a position under this rank a sailor had to have at least two years of experience as an Ordinary Seaman, therefore it was likely that Henry would have been at sea from at least 1854 where his duties may have been sweeping and washing the deck, working with the rigging and securing the cargo. What did Henry do in those few years between leaving school and the beginning of his life at sea? One place he could have worked and where he would have learned the basics of seamanship was with local fishermen who he could find most days on the Polkerris beach. A position on board a fishing vessel, catching pilchards, which were common in the seas around Cornwall, would be a perfect way to gain some experience and build up his strength. The romantic in me sees Henry standing on the end of Polkerris’s half-moon quay, watching the fine-masted sailing ships leave from the port of Fowey with cargo that was set for places all over the globe, his imagination fuelled by his father's stories of his life in Portsea where men sailed away in magnificent galleons.

Henry, at his full adult height, was only 5ft 4in, I imagine then that he would have been under the expected height to join the Royal Navy, if the merchant navy were adopting the same practices then it is likely that he may have been rejected by the merchant navy too. Henry, it appears, was short in stature and may have appeared physically weak, until he bulked up there may have been no chance, under the new rules that he could go to sea. I wonder though, in reality, were these rules actually applied? If they were, it may account for the five-year gap between Henry leaving school and the first time he is recorded on board ship. Henry’s service record shows that the first time he went to sea as an Able Seaman was on the 2nd September 1856 where his duties concerned the operation and upkeep of deck department areas and equipment. To take up a position under this rank a sailor had to have at least two years of experience as an Ordinary Seaman, therefore it was likely that Henry would have been at sea from at least 1854 where his duties may have been sweeping and washing the deck, working with the rigging and securing the cargo. What did Henry do in those few years between leaving school and the beginning of his life at sea? One place he could have worked and where he would have learned the basics of seamanship was with local fishermen who he could find most days on the Polkerris beach. A position on board a fishing vessel, catching pilchards, which were common in the seas around Cornwall, would be a perfect way to gain some experience and build up his strength. The romantic in me sees Henry standing on the end of Polkerris’s half-moon quay, watching the fine-masted sailing ships leave from the port of Fowey with cargo that was set for places all over the globe, his imagination fuelled by his father's stories of his life in Portsea where men sailed away in magnificent galleons.

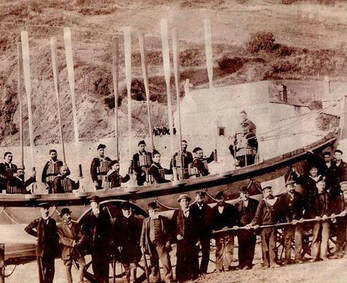

Henry’s education ended at the beginning of the pilchard season when the annual shoals of this little silvery fish appeared off the Cornish coast and when local fishermen would be taking to their boats, maybe Henry went along with them. Cornish fishermen used seine nets, which were large nets with weighted bottoms that were dragged through the water. Once the net was full and the boat was close to shore the fish was ‘tucked’ using a small tuck net. This operation ‘is always performed at low water, the number of boats sailing or rowing in all directions around the seine; the quantity of persons employed in taking up the fish with baskets; the refulgent appearance of the scaly tribe, struggling, springing and gleaming to the moon in every direction, the busy and contented hum of the fishermen, together with the plashing of the frequently-plying oar.'

The pilchard, commonly known as a sardine, was later pressed and salted and then exported to Italy. By November the season ended and Henry would have to find work elsewhere, if the large sailing ships did indeed fascinate Henry, this time would be the perfect opportunity to seek employment on one of those ships. Young men and women leaving school would rely on local connections to find work, there was his father of course, and there was fisherman and sailors who frequented the local inn. In Henry’s case would have been The General Elliott (later the Rashleigh Inn) maybe some of these men would have known someone who was in need of an enthusiastic worker. If Henry did not take up employment among the local fisherman then he may have looked to his older brother. It was probably via this route that found his first real job, William was five years older than Henry, and was, as you might expect a mariner.

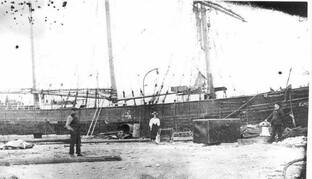

William had made the acquaintance of one John Tregaskas, the son of a maltster of St Blazey. The Tregaskas were an important family in Par and were influential in the careers of the Purches.’ John’s first job was as an office clerk, within a few years he had married Susan Hoal, whose grandfather Jonathan Hoal had been a victualler and licensee of the Par Inn in St Blazey. By 1873, John and Susan had taken over the running of the inn and from where John practiced as an accountant. By this time William had been a mariner on and off for twenty years, in 1861 he was an innkeeper in Twardreath, ten years later he was employed as a steel worker in Barrow in Lancashire. William returned to Par at more or less the same time that John Tregaskas had taken up the position of harbour master. Tregaskas went on to own a dry dock in Par, which would have been purpose-built for the construction, repair and maintenance of vessels. An early 20th-century photograph shows a schooner called the Pedestrian being repaired in Tregaskas’s dock. John Tregaskas was also a ship broker and William was soon captaining schooners out of Par, and in 1881 he can be found as part owner and captain of the aforementioned Pedestrian. In 1887, John’s brother-in-law died and it was probably that year that William, with experience in running a hostelry, took over the running of the Par Inn. William would manage this public house until his death in 1904. It would seem that the families of John Tragaska and his wife Susan Hoal either personally or via their contacts were able to help William, Henry and later Henry’s son Robert.

It was out of the port of Fowey that Henry first set sail on his seafaring career.

William had made the acquaintance of one John Tregaskas, the son of a maltster of St Blazey. The Tregaskas were an important family in Par and were influential in the careers of the Purches.’ John’s first job was as an office clerk, within a few years he had married Susan Hoal, whose grandfather Jonathan Hoal had been a victualler and licensee of the Par Inn in St Blazey. By 1873, John and Susan had taken over the running of the inn and from where John practiced as an accountant. By this time William had been a mariner on and off for twenty years, in 1861 he was an innkeeper in Twardreath, ten years later he was employed as a steel worker in Barrow in Lancashire. William returned to Par at more or less the same time that John Tregaskas had taken up the position of harbour master. Tregaskas went on to own a dry dock in Par, which would have been purpose-built for the construction, repair and maintenance of vessels. An early 20th-century photograph shows a schooner called the Pedestrian being repaired in Tregaskas’s dock. John Tregaskas was also a ship broker and William was soon captaining schooners out of Par, and in 1881 he can be found as part owner and captain of the aforementioned Pedestrian. In 1887, John’s brother-in-law died and it was probably that year that William, with experience in running a hostelry, took over the running of the Par Inn. William would manage this public house until his death in 1904. It would seem that the families of John Tragaska and his wife Susan Hoal either personally or via their contacts were able to help William, Henry and later Henry’s son Robert.

It was out of the port of Fowey that Henry first set sail on his seafaring career.

The town of Fowey (pronounced Foy) sits on the mouth of the River Fowey. It has a large natural harbour which is deep enough to accommodate large vessels enabling trade within Europe. Tudor antiquary John Leland wrote of Fowey " It is set on the north side of the haven, lying along the shore, and builded on the side of a great slatey, rokkeil hille." In Henry’s time, the town had spread a little further afield. Ships have sailed in and out of this port for generations, Roman coins and pottery, dated to the time of Emperor Vespasian have been found, and during the reign of Edward III, ships headed out of Fowey to aid the English at the Siege of Calais. In 1829, Joseph Treffry shipped copper from Caffa Mill Pill above Fowey before starting work on his new harbour at Par, it would however take another forty years before Fowey would begin to take the ships that carried copper and china clay.

In the 19th century, Britain’s wealth relied on merchant ships, they were considered to be the best in the world. In Henry’s early years at sea, the ships that sailed out of Fowey were wooden vessels that were propelled by the wind, Henry sailed in schooners, packets, barques and brigantines. The schooner was light and with a good wind was able to skip across the water, it was versatile and could be used to sail the oceans or along the coastline and was usually manned by a small crew of about six. These wooden ships were owned and built locally by such families as the Butsons, who owned a yard at Lanteglos and one Charles Toms had a boat yard at Polruan. Schooners, the type of vessel that Henry worked on were moored side by side on what was originally called Broad Slip. Following a visit from Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1846, the slipway was filled in and renamed Albert Quay. Henry would be familiar with this quay, with its harbour master's office right on the edge of the river and the alleyways with their lodgings and inns. In the August of 1869, when Henry was away at sea on board the schooner Heron, the first meeting of the newly formed Fowey Harbour Commissioners was held in the Town Hall, these men would be responsible for the estuary and commercial operations.

In the 19th century, Britain’s wealth relied on merchant ships, they were considered to be the best in the world. In Henry’s early years at sea, the ships that sailed out of Fowey were wooden vessels that were propelled by the wind, Henry sailed in schooners, packets, barques and brigantines. The schooner was light and with a good wind was able to skip across the water, it was versatile and could be used to sail the oceans or along the coastline and was usually manned by a small crew of about six. These wooden ships were owned and built locally by such families as the Butsons, who owned a yard at Lanteglos and one Charles Toms had a boat yard at Polruan. Schooners, the type of vessel that Henry worked on were moored side by side on what was originally called Broad Slip. Following a visit from Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1846, the slipway was filled in and renamed Albert Quay. Henry would be familiar with this quay, with its harbour master's office right on the edge of the river and the alleyways with their lodgings and inns. In the August of 1869, when Henry was away at sea on board the schooner Heron, the first meeting of the newly formed Fowey Harbour Commissioners was held in the Town Hall, these men would be responsible for the estuary and commercial operations.

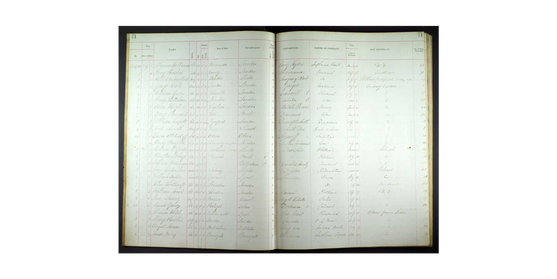

Much of what is known about Henry’s career at sea can be found in a document entitled A List of Testimonials and Statement of Service. This list gives information on the name of the ships on which he sailed, their port of registration, his rank and the dates and length of the time spent on the ship. From this, we know that Henry was a sailor from 1856 until 1879, we also know from this list that there are voyages on which he had no official documentation but were accounted for when calculating his total years at sea. Other documents appertaining to Henry's career are an Application to be Examined for a Certificate of Competency, and of course, the certificates themselves. What isn’t clear from these documents is where his ship set sail from, where it stopped off during its voyage, or its destination. From this information, it cannot be assumed that each ship set off from the port in which it was registered and this makes it difficult to really know exactly where Henry was, where he signed on for his next voyage, and how many times he made it home to Cornwall. However, this paperwork gives us a very good idea of where Henry had travelled.

Henry’s first years at sea are not covered in the aforementioned paperwork, but he would have had enough experience as an Ordinary Seaman to raise to the rank of Able Seaman, and as such on the 2nd September in 1856 he set sail from the port of Fowey on board the Wanderer, and from that date, until the 9th May 1859 Henry had spent a total of nearly two years at sea sailing on board five different vessels. It is easy to fall into the trap of over-romanticising life at sea - we can look to Joseph Conrad for his experiences for the reality of it. For men like Conrad and Henry, it was hard and sometimes brutal, bad weather, poorly maintained ships, and disenchantment among the crew made life on board a dangerous place to be. When one job was finished mariners like Henry took the next job that was available, more often than not these men sailed with those they did not know or may have even disliked, but once a sailor had signed up, and there was a problem, they were stuck with it until their voyage was completed.

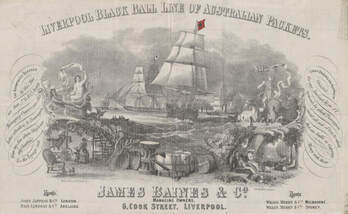

On the 9th of May in 1859, Henry arrived in the port of Liverpool having spent just over two months at sea on board the Little Liz, a packet out of Cornwall. He was, no doubt hoping to find work as soon as possible and it was not long before a new position became available on board the Commodore Percy, a 1964/2017 ton clipper which was a long narrow vessel that was designed for speed. It had been built in 1854 by shipbuilder Donald McKay in Boston in the United States for Liverpool based James Baines and Company as part of his Black Ball Line. This ship formed part of a fleet running cargo and passenger services between Liverpool and Australia capitalising on the Australian Gold Rush. James Baines ships also transported troops to Crimea and to India to aid forces during the Indian Mutiny. The Commodore Perry was to sail to Australia, whether Henry signed up immediately or it was at the last minute decision is not known, what is known however, is that he had two weeks before he was due to set sail.

Henry’s first years at sea are not covered in the aforementioned paperwork, but he would have had enough experience as an Ordinary Seaman to raise to the rank of Able Seaman, and as such on the 2nd September in 1856 he set sail from the port of Fowey on board the Wanderer, and from that date, until the 9th May 1859 Henry had spent a total of nearly two years at sea sailing on board five different vessels. It is easy to fall into the trap of over-romanticising life at sea - we can look to Joseph Conrad for his experiences for the reality of it. For men like Conrad and Henry, it was hard and sometimes brutal, bad weather, poorly maintained ships, and disenchantment among the crew made life on board a dangerous place to be. When one job was finished mariners like Henry took the next job that was available, more often than not these men sailed with those they did not know or may have even disliked, but once a sailor had signed up, and there was a problem, they were stuck with it until their voyage was completed.

On the 9th of May in 1859, Henry arrived in the port of Liverpool having spent just over two months at sea on board the Little Liz, a packet out of Cornwall. He was, no doubt hoping to find work as soon as possible and it was not long before a new position became available on board the Commodore Percy, a 1964/2017 ton clipper which was a long narrow vessel that was designed for speed. It had been built in 1854 by shipbuilder Donald McKay in Boston in the United States for Liverpool based James Baines and Company as part of his Black Ball Line. This ship formed part of a fleet running cargo and passenger services between Liverpool and Australia capitalising on the Australian Gold Rush. James Baines ships also transported troops to Crimea and to India to aid forces during the Indian Mutiny. The Commodore Perry was to sail to Australia, whether Henry signed up immediately or it was at the last minute decision is not known, what is known however, is that he had two weeks before he was due to set sail.

The City of Liverpool, at the beginning of the 18th century, was just a small town, but by the end of the following century its population had risen and new buildings such as St Georges Hall and Lime Street Station reflected its wealth. While sailing up the Mersey on the Little Liz, Henry would have seen for himself the newly built Albert Dock that had been opened in 1846. Maybe it was at the dock that the Little Liz docked and her cargo unloaded. Once Henry disembarked I very much doubt that he headed into town, when transient seamen like Henry first stepped ashore after a long and arduous journey they would make straight for Sailortown, a place that catered specifically to their needs, there would be boarding houses, inns, brothels, shops and churches, and probably a tattoo parlour. These places with a reputation for exuberance and excess and I have to wonder where twenty-two year old Henry spent his time, nine years later however, an episode in his life might just give us a clue! Sailortown was not all drunkenness and debauchery though, Liverpool had a Sailor's Home, a place designed to provide safe, inexpensive lodging, and to offer educational and recreational opportunities, in contrast to the temptations on offer in the docklands area. This building, on Canning Street, offered a

' reading-room, library, and savings bank will be attached to the institution; and with a view to securing to the able and well-conducted seamen a rate of wages proportionate to his merits, a registry of character will be kept. Among the ulterior objects in contemplation are schools for sea-apprentices, and the sons of seamen, with special regard to the care of children who have lost one or both their parents receiving religious instruction.'

Where Henry went, where he stayed and what he did goes unrecorded but what is recorded is that Henry boarded the Commodore Perry on the 19th May 1859. According to the Statement of Service issued by the Board of Trade, Henry was on board the Commodore Perry for six months and seven days, this length of time suggests that Henry worked both the outward and homeward passage.

It was the norm that vessels that relied on the wind to propel them anchored on River Mersey overnight and then were towed out to sea and their sails set. When the wind caught in the clipper’s sails Henry would begin his journey. Little did Henry know that conditions on board the ships that made up the Black Ball Line were known to be appalling, passengers and crew lived in cramped quarters, and the ships were also dirty and poorly ventilated. One consolation for all on this journey was that in this period sailing ships were reaching their fastest speeds. Between 1854 and 1855, the Lightning, another of James Baines American built clippers, sailed from Liverpool to Australia and back in five months nine days which included twenty days in port. On a previous journey to Australia the Commodore Perry sailed from Liverpool to Sydney, and on board were over thirty crew members and nearly two-hundred passengers, and it was not uncommon to have up to five-hundred passengers on one vessel. For the emigrants paying for their passage, handbooks were available, P B Chadfield’s book Out to Sea: Or the Emigrant Afloat was one of them, these books were to help them prepare for the voyage that would be a long and dangerous one. As a crew member, Henry did not have the ‘luxuries’ afforded those who paid for their passage. His duties were many, he was expected to perform general maintenance of the ship's structure including rigging, and be capable of operating deck machinery, he may even have acted as a helmsman, but he was however, expected to go about his tasks without complaint. As The Commodore Perry sailed into the horizon I wonder what these men, women and children, most of who were travelling for the first time, expected from their journey, those who had may have kept their thoughts to themselves.

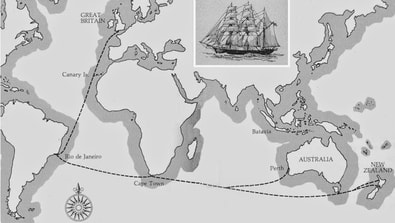

On the outbound journey, it is likely that the Commodore Perry stopped off in the Bay of Biscay before heading south to the equator and may have stopped again for supplies along the way, maybe at Cape Town or Rio de Janeiro. Sailing ships running this passage could spend weeks in port waiting for the wind to get up or once out at sea they may be becalmed for as long as three weeks in what is called the doldrums, a belt around the earth near the equator where sailing ships got stuck in windless waters. Then there were freezing conditions and there was always a danger of being hit by an iceberg. It may be that the outbound passage was event free, in calm weather for instance, a sailing ship might take as long as four months, while a well-run clipper ship with favourable winds could make the journey in a little over half that time. The record for Henry’s time on this vessel doesn’t state when it arrived in Australia, but the crew would have had about two weeks before they were expected to set sail again.

On the outbound journey, it is likely that the Commodore Perry stopped off in the Bay of Biscay before heading south to the equator and may have stopped again for supplies along the way, maybe at Cape Town or Rio de Janeiro. Sailing ships running this passage could spend weeks in port waiting for the wind to get up or once out at sea they may be becalmed for as long as three weeks in what is called the doldrums, a belt around the earth near the equator where sailing ships got stuck in windless waters. Then there were freezing conditions and there was always a danger of being hit by an iceberg. It may be that the outbound passage was event free, in calm weather for instance, a sailing ship might take as long as four months, while a well-run clipper ship with favourable winds could make the journey in a little over half that time. The record for Henry’s time on this vessel doesn’t state when it arrived in Australia, but the crew would have had about two weeks before they were expected to set sail again.

Henry must have been relieved to be ashore, but as the time to reboard the Commodore Perry grew near he may have thought back to those days in Liverpool and realised, in the context of a passenger ship, that he may have made a mistake and was maybe having doubts about the return journey. It was not that he had never spent months at sea, his longest period away had been nine months, it could not have been the size of the vessel, he had sailed on the big sailing ships before. I wonder if he was overwhelmed by the conditions and sheer volume of people and maybe it was in port in Australia that he first considered not returning. Henry was a young man, but an experienced sailor and he must have realised that it would be better to continue the journey than to be stuck in a foreign port without the hope of finding a suitable ship back. Henry did return to the Commodore Perry and the ship set sail for Liverpool using a variation of the Brouwer Route, a route ships used between Europe, Australia, New Zealand and the Far East. This route ran from west to east through the Antarctic Ocean making use of the Roaring Forties ‘strong westerly winds found in the Southern Hemisphere caused by the combination of air being displaced from the Equator towards the South Pole’ If Henry was lucky the Commodore Perry may have had a reasonable inward journey, but this did not mean the outward would be the same. Many ships and sailors were lost in the heavy conditions along this route, particularly around Cape Horn as they made their way into the South Atlantic Ocean and then northward toward Europe. This route would eventually be abandoned with the introduction of steamships and the opening of the Suez and Panama Canal.

On the Commodore Perry's voyage home, it sailed east, and Henry would once again feel icy blasts of wind blowing across the deck as the ship sailed along the 56th parallel - an invisible line where there is no land and nothing but ocean. If Henry was again having second thoughts about the trip then would have to be here with Cape Horn looming on the horizon. Cape Horn, a place of notoriously storming conditions, is a rocky point on the southernmost tip of the Tierra del Fuego peninsula, hundred’s of ships have gone down there since it was first navigated at the beginning of the 17th century. At Cape Horn, strong winds and currents flow without interruption and are funnelled by the Horn into a narrow passage named after Sir Francis Drake. The sea here is considered the most difficult maritime passage in the world. One famous vessel that escaped such a fate was the HMS Beagle with Charles Darwin onboard. Darwin wrote of his first view of the Horn ‘... when we saw on our weather-bow this notorious promontory in is proper form - veiled in a mist, and its dim outline surrounded by storm of wind and water. Great black clouds were rolling across the heavens, and squalls of rain, with hail, swept by us with extreme violence’

Cape Horn had a bad reputation with sailors, it has been said of it that 'below 40 degrees latitude, there is no law; below 50, there is no God.'

On the Commodore Perry's voyage home, it sailed east, and Henry would once again feel icy blasts of wind blowing across the deck as the ship sailed along the 56th parallel - an invisible line where there is no land and nothing but ocean. If Henry was again having second thoughts about the trip then would have to be here with Cape Horn looming on the horizon. Cape Horn, a place of notoriously storming conditions, is a rocky point on the southernmost tip of the Tierra del Fuego peninsula, hundred’s of ships have gone down there since it was first navigated at the beginning of the 17th century. At Cape Horn, strong winds and currents flow without interruption and are funnelled by the Horn into a narrow passage named after Sir Francis Drake. The sea here is considered the most difficult maritime passage in the world. One famous vessel that escaped such a fate was the HMS Beagle with Charles Darwin onboard. Darwin wrote of his first view of the Horn ‘... when we saw on our weather-bow this notorious promontory in is proper form - veiled in a mist, and its dim outline surrounded by storm of wind and water. Great black clouds were rolling across the heavens, and squalls of rain, with hail, swept by us with extreme violence’

Cape Horn had a bad reputation with sailors, it has been said of it that 'below 40 degrees latitude, there is no law; below 50, there is no God.'

Aboard these ships, the crew were likely to experience cyclones, run into shallow water, or deal with waves up to forty feet high. Despite July and August being the wettest months at the Cape, Henry and The Commodore Perry survived and sailed northwards into the Atlantic Ocean. As they approached the equator, and with the warmer wind in her sails, the Commodore Perry continued into the South Atlantic, maybe calling in at Rio de Janeiro or one of the Caribbean Islands before heading east into the North Atlantic Ocean until she finally docked at the Port of St Johns in Newfoundland. From here she would set sail northeast and home to Liverpool. The final part of the journey across the Atlantic Ocean would take between twenty-one and twenty-nine days, why then did Henry not make it back to Liverpool? Henry’s service statement not only tells us that he boarded a different ship out of St Johns twelve days after arriving, but it also tells us that he had deserted his post on the Commodore Perry. Unfortunately, it does not give a reason.

Desertion is the abandonment of duty that is often associated with life in the military, but it also applies to members of the Merchant Navy. Henry’s desertion would be seen as an abandonment of his post with the intention of not returning. If a sailor leaves that employment prematurely he is said to have jumped ship. This probably stems from the practice of literally jumping off a ship as it nears or leaves a port and swimming to freedom. It was particularly prevalent in earlier centuries when sailors were often shanghaied or pressed into service aboard ships against their wills.

In Henry's case he disembarked from the Commodore Perry on the 10th of November 1859, he had I assume, already made his mind up that he would not return. Why did Henry do this, why could he not face fourteen more days when he had spent one hundred and eighty-seven at sea already? Was it the conditions on board he’d experienced on the outward passage that caused him to abandon his post, did he have a run-in with a crew member, did he commit some kind of offense whilst at sea that would be punishable once he returned to England? Sadly, there is no answer, Henry, it would appear simply did not turn up when Commodore Perry left Newfoundland and was listed as a deserter in Liverpool when his paperwork was completed by the ship's captain. Would the officials seek to find Henry? Perhaps they might, ship owners could not afford for men to jump ship with no fear of punishment, on the other hand maybe they accepted that some sailors would not always return to their ship in foreign ports, non-payment of their wages at the end of a journey may have been a deterrent for some. This did not deter Henry and neither did the risk of imprisonment as the refusal to reboard a ship could result in a criminal prosecution - in 1850 for instance, British prison inspectors noted that three-quarters of men incarcerated in prisons in the southwest of England were sailors. Henry’s records show that he never returned to Liverpool.

Desertion is the abandonment of duty that is often associated with life in the military, but it also applies to members of the Merchant Navy. Henry’s desertion would be seen as an abandonment of his post with the intention of not returning. If a sailor leaves that employment prematurely he is said to have jumped ship. This probably stems from the practice of literally jumping off a ship as it nears or leaves a port and swimming to freedom. It was particularly prevalent in earlier centuries when sailors were often shanghaied or pressed into service aboard ships against their wills.

In Henry's case he disembarked from the Commodore Perry on the 10th of November 1859, he had I assume, already made his mind up that he would not return. Why did Henry do this, why could he not face fourteen more days when he had spent one hundred and eighty-seven at sea already? Was it the conditions on board he’d experienced on the outward passage that caused him to abandon his post, did he have a run-in with a crew member, did he commit some kind of offense whilst at sea that would be punishable once he returned to England? Sadly, there is no answer, Henry, it would appear simply did not turn up when Commodore Perry left Newfoundland and was listed as a deserter in Liverpool when his paperwork was completed by the ship's captain. Would the officials seek to find Henry? Perhaps they might, ship owners could not afford for men to jump ship with no fear of punishment, on the other hand maybe they accepted that some sailors would not always return to their ship in foreign ports, non-payment of their wages at the end of a journey may have been a deterrent for some. This did not deter Henry and neither did the risk of imprisonment as the refusal to reboard a ship could result in a criminal prosecution - in 1850 for instance, British prison inspectors noted that three-quarters of men incarcerated in prisons in the southwest of England were sailors. Henry’s records show that he never returned to Liverpool.

Within twelve days Henry had found a new position on board the Harmonides, a 1564-ton ship registered in St Johns. In this time period, Newfoundland exported salt fish to Brazil, the West Indies and countries like Spain, Portugal and Italy. They also exported seal products to Britain where there was a demand for seal oil and leather, they also exported copper and wood. Henry sailed out of St John’s onboard the Harmonides on the 22nd November 1859 with one of the aforementioned cargoes bound. This time Henry would spend ten months and eleven days at sea and on the 2nd October of 1860 he disembarked from the Harmondies in London. The Harmonies, no doubt, would have picked up a cargo and headed home to Newfoundland without Henry.

Henry’s next post was on the Ann Whyte, a 198-ton ship out of London, his service statement shows that Henry served on this vessel for one year, eleven months and twenty-four days and this appears to be his longest journey as an Able Seaman. The length of a journey such as this suggests that the Anne Whyte sailed to China and the Japanese archipelago. Henry ended his service on the Ann Whyte on the 1st March 1862, disembarking in Fowey in Cornwall, it would appear to be the first time home in nearly six years. At twenty-five, he had had enough, Henry would not take up any positions onboard large sailing ships sailing across the treacherous oceans of the southern hemisphere again until he captained his own ships.

The oceans of the world were hard taskmasters, the early explorers, those men who fought in sea battles and merchant seamen like Henry all shared similar experiences and had much to endure. They were cut off from normal life for months, had to accept cramped conditions, disease, poor food and poor pay and spent their daily lives in danger from the sea and the weather. There are no family stories that give us an insight into the reasons Henry chose not to return to life on those ocean-going ships, but I feel sure it must have been linked to his experience onboard The Commodore Perry. Henry returned home a changed man, but he would also find that much had changed. He may not have known that his father had died and that his siblings were married and had left home. Only Emma, his younger sister remained with their mother. Henry appears to have stayed in Cornwall for at least the next six months (there is no record of him being elsewhere) It was maybe during this period that Henry made up his mind to work the English coastal routes where he could return home within months rather than years. He would have been familiar with the coasters that sailed these routes. A coaster was a small-sized vessel with a shallow hull that consisted of cargo holds and stowage areas which required less crew to operate. Two such ships, the Perseverance and the aforementioned Pedestrian, were built and repaired in Par Harbour.

Henry’s next post was on the Ann Whyte, a 198-ton ship out of London, his service statement shows that Henry served on this vessel for one year, eleven months and twenty-four days and this appears to be his longest journey as an Able Seaman. The length of a journey such as this suggests that the Anne Whyte sailed to China and the Japanese archipelago. Henry ended his service on the Ann Whyte on the 1st March 1862, disembarking in Fowey in Cornwall, it would appear to be the first time home in nearly six years. At twenty-five, he had had enough, Henry would not take up any positions onboard large sailing ships sailing across the treacherous oceans of the southern hemisphere again until he captained his own ships.

The oceans of the world were hard taskmasters, the early explorers, those men who fought in sea battles and merchant seamen like Henry all shared similar experiences and had much to endure. They were cut off from normal life for months, had to accept cramped conditions, disease, poor food and poor pay and spent their daily lives in danger from the sea and the weather. There are no family stories that give us an insight into the reasons Henry chose not to return to life on those ocean-going ships, but I feel sure it must have been linked to his experience onboard The Commodore Perry. Henry returned home a changed man, but he would also find that much had changed. He may not have known that his father had died and that his siblings were married and had left home. Only Emma, his younger sister remained with their mother. Henry appears to have stayed in Cornwall for at least the next six months (there is no record of him being elsewhere) It was maybe during this period that Henry made up his mind to work the English coastal routes where he could return home within months rather than years. He would have been familiar with the coasters that sailed these routes. A coaster was a small-sized vessel with a shallow hull that consisted of cargo holds and stowage areas which required less crew to operate. Two such ships, the Perseverance and the aforementioned Pedestrian, were built and repaired in Par Harbour.

The English coastal shipping routes played an important part in the growth of the country and greatly contributed to its domestic trade. As the size of towns increased, and transportation by land became more expensive (it required only six or eight men to bring by water to London the same quantity of goods which would otherwise require fifty broad-wheeled wagons, attended by a hundred men, and drawn by four hundred horses.) The newly industrialised towns in the midlands became dependent on the sailing coaster to bring coal, iron and copper ore and china clay. The population was reliant on them too, these coasters carried bricks, stone, slate and timber to build homes and businesses and also carried grain, dairy products and fish for food. Henry’s first position working these coastal routes was onboard the Carthagerian, he left Fowey on the 11th of October 1862 for a three-month and twenty-nine-day voyage ending in what was then Shields (now North and South Shields) in Tyne and Wear. Out of Shields he sailed aboard the Quilla to London and disembarked on the 13th of March 1863. It was on the 9th of July 1864 that Henry worked his last trip as an Able Seaman, this was onboard the Constance sailing out of London on an eleven-month eighteen-day voyage. On the 25th of July of the following year, Henry passed to the position of Mate. The documentation attached to his Certificate of Competency states that he had spent fourteen years at sea. This accompanying document breaks down Henry’s time at sea. For six years, seven months and twenty-two days of his career Henry was able to produce documentation, and for the seven years four months and eight days there he presented no paperwork. The examiners signed Henry off as an able seaman on the 26th of July 1865.

A Mate on board a merchant ship was a licensed crew member who would have had more responsibility than those of a lower rank. Today’s merchant navy has three ranks, Mate - first, second and third - the first being the most senior. In 1865, when Henry qualified there were two, Mate and Ordinary Mate (First Mate) The latter is usually second in command to the Captain. The size of these coastal trading ships meant that less crew was needed and usually consisted of two senior ranks - a captain and a first mate and up to ten others of lower ranks to work on the rigging, the deck, loading, and unloading the cargo. As a newly qualified mate, Henry’s responsibilities were overseeing the different jobs during the vessel's journey and seeing that orders were followed. Henry would have been sensible enough to know that sailing the waters of England's coast was no less a danger to life than sailing the oceans of the world, as the majority of the coastline could be difficult to navigate due to their natural geographic features. With this in mind, on the 30th of August 1865, Henry headed out of Fowey as a Mate on board the aforementioned Perseverance, a ship that was built and repaired in the shipyard of the Tregaskas family on a four-month, nine-day voyage that ended in London.

The statement of service, a document that records the career of merchant seamen, only records the length of a ship's voyage, it does not mention the other ports to which the ship called. It may have been anywhere, between Fowey and London that Henry picked up a sexually transmitted disease. We know this about Henry because his name appears in the Dreadnought Seamans Hospital Admission and Discharge Book.

A Mate on board a merchant ship was a licensed crew member who would have had more responsibility than those of a lower rank. Today’s merchant navy has three ranks, Mate - first, second and third - the first being the most senior. In 1865, when Henry qualified there were two, Mate and Ordinary Mate (First Mate) The latter is usually second in command to the Captain. The size of these coastal trading ships meant that less crew was needed and usually consisted of two senior ranks - a captain and a first mate and up to ten others of lower ranks to work on the rigging, the deck, loading, and unloading the cargo. As a newly qualified mate, Henry’s responsibilities were overseeing the different jobs during the vessel's journey and seeing that orders were followed. Henry would have been sensible enough to know that sailing the waters of England's coast was no less a danger to life than sailing the oceans of the world, as the majority of the coastline could be difficult to navigate due to their natural geographic features. With this in mind, on the 30th of August 1865, Henry headed out of Fowey as a Mate on board the aforementioned Perseverance, a ship that was built and repaired in the shipyard of the Tregaskas family on a four-month, nine-day voyage that ended in London.

The statement of service, a document that records the career of merchant seamen, only records the length of a ship's voyage, it does not mention the other ports to which the ship called. It may have been anywhere, between Fowey and London that Henry picked up a sexually transmitted disease. We know this about Henry because his name appears in the Dreadnought Seamans Hospital Admission and Discharge Book.

In 1821, The Dreadnought Seamans Hospital was at Greenwich and was founded as an infirmary hospital ship to care for sick or injured sailors. Between 1821 and 1870 three ships were used, the HMS Grampus, the HMS Dreadnought and the HMS Caledonia which was later renamed the Dreadnought. In 1869, the care of seaman was transferred to land, to a hospital on the site of the former Royal Greenwich Hospital. This new hospital was named The Dreadnought Seamans Hospital after the last of the floating hospitals.

It was on board the last of these ships, The Dreadnought, that Henry found himself in the first week of February 1866. The Perseverance arrived in London on the 8th of January and within a few weeks he was probably suffering from swollen and sore lymph nodes in the groin, sores on the genitals and a burning sensation when passing water. By the 5th of February, less than a month after arriving in the city Henry entered the hospital ship, Henry’s record confirms that he was suffering from a venereal disease but doesn’t specify which, therefore it could have been anything from chlamydia, genital herpes, gonorrhea or even syphilis.

In the mid-19th century, venereal disease was seen as the 'chief and most enduring scourge of seamen in all parts of the world’ and a ‘self-inflicted disease’ Because of this there were concerns about its increase among soldiers and sailors, and a call was made for the regulating and punishment of those seen to be responsible for their spread - not the sailor, but the sex workers. Following the Crimean War, the Government passed a series of Contagious Diseases Acts and under this legislation, police officers could arrest and examine any woman found within a certain distance of army or navy barracks, and this in turn affected the lives of thousands of working-class women who made a living in the sex trade. This, quite rightly, initiated a debate over inequality between men and women. Victorian reformer and feminist Josephine Butler called to have these laws repealed. In one of her many pamphlets on this subject, she allowed a prostitute to deliver her own account of her personal encounters with men:

'It is men, only men, from the first to the last that we have to do with! To please a man I did wrong at first, then I was flung about from man to man. Men police lay hands on us. By men, we are examined, handled, and doctored. In the hospital, it is a man again who makes prayers and reads the Bible for us. We are had up before magistrates who are men, and we never get out of the hands of men till we die!

And men for their part thought 'Everyone knows what sailors do: they get drunk and go looking for sex; it has always been that way.'

In the mid-19th century, venereal disease was seen as the 'chief and most enduring scourge of seamen in all parts of the world’ and a ‘self-inflicted disease’ Because of this there were concerns about its increase among soldiers and sailors, and a call was made for the regulating and punishment of those seen to be responsible for their spread - not the sailor, but the sex workers. Following the Crimean War, the Government passed a series of Contagious Diseases Acts and under this legislation, police officers could arrest and examine any woman found within a certain distance of army or navy barracks, and this in turn affected the lives of thousands of working-class women who made a living in the sex trade. This, quite rightly, initiated a debate over inequality between men and women. Victorian reformer and feminist Josephine Butler called to have these laws repealed. In one of her many pamphlets on this subject, she allowed a prostitute to deliver her own account of her personal encounters with men:

'It is men, only men, from the first to the last that we have to do with! To please a man I did wrong at first, then I was flung about from man to man. Men police lay hands on us. By men, we are examined, handled, and doctored. In the hospital, it is a man again who makes prayers and reads the Bible for us. We are had up before magistrates who are men, and we never get out of the hands of men till we die!

And men for their part thought 'Everyone knows what sailors do: they get drunk and go looking for sex; it has always been that way.'

On average, a man suffering from a venereal disease usually did not work for at least a month, and records show that one out of every three men on board the Dreadnought suffered from venereal disease. On page forty-four, the page of the Dreadnought admissions book that shows Henry’s entry, there were twenty-five men listed - another three have venereal disease. Henry’s stay on board the Dreadnought lasted for three days and he is listed as convalescing, which suggests that he may have been ill previous to entering, but with whatever complaint he had the worst of his symptoms were over and he was discharged from the hospital on the 8th of February and took up a position on board the Johns thirteen days later.

During the following years, Henry was a Mate on board another four ships, the Alliance, the Yana, the Viviandiere and the Heron, out of North and South Shields, Brixham and Cardiff respectively. Henry’s last position as a Mate was on board the Flower of the Fal. Stepping off this ship Henry would have served as a Mate for a total of three years, one month and twenty-seven days. Henry next appears on official records on 23rd July 1870, when he applied for his Master's Certificate.

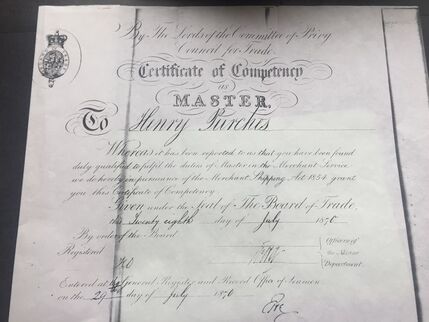

Captaining a sailing ship was a great responsibility and as such Henry needed to be able to "command, the candidate had to know how to navigate by the planets and the moon. These bodies introduce extra corrections. Latitude by Polaris, using a complex method involving logarithms, was required, together with advanced knowledge of the compass and its errors." Having proved he could, Henry was issued his Certificate of Competency in the Port of Bristol on the 28th July 1870. He was now a Master Mariner.

Master is a term that has been in use at least since the 13th century, reflecting the fact that in guild or livery company terms, such a person was a master craftsman in this specific profession.

Captaining a sailing ship was a great responsibility and as such Henry needed to be able to "command, the candidate had to know how to navigate by the planets and the moon. These bodies introduce extra corrections. Latitude by Polaris, using a complex method involving logarithms, was required, together with advanced knowledge of the compass and its errors." Having proved he could, Henry was issued his Certificate of Competency in the Port of Bristol on the 28th July 1870. He was now a Master Mariner.

Master is a term that has been in use at least since the 13th century, reflecting the fact that in guild or livery company terms, such a person was a master craftsman in this specific profession.

According to his youngest son, Henry had received his Extra Master Certificate, which is the highest rank of seafarer's qualification, which meant that he would be allowed to serve as the master of a merchant ship of any size, of any type, operating anywhere in the world. This reflected the highest level of professional qualification amongst mariners and deck officers. As with the application for a Master's Certificate to gain an Extra Master's Certificate, Henry would have to prove that he could solve problems of considerable complexity, for instance using spherical trigonometry. As part of the examination Henry would have taken he would have had to answer questions like ‘can you determine the great circle course from a point on the Kamchatka Peninsula, in Russia, to Cape Horn, listing all the turning points on the course and the courses to be steered between them, assuming the course is changed every 10° of longitude?’ A calculation that could take up to two pages! He might be asked to explain the reasoning behind the celestial navigation or construct a Mercator chart from scratch. He would have been required to write essays on nautical topics and draw diagrams in a neat and methodical way. The examination that Henry took would have taken could have lasted up to twenty-six hours spread over five days. Following an oral examination, Henry would have been told of his success or failure immediately. I have found no records to prove that Henry did pass to the rank of Extra Master, but this does not mean that they didn’t exist, only that they are missing. The National Maritime Museum supplied me with all of Henry's documentation appertaining to his sea-faring career, yet his voyages as a captain were incomplete, as was the list of some of his known voyages.

Obtaining a position as a newly qualified captain would have been difficult, Henry had proved that he was capable on paper, however, actually entrusting Henry with a fine-masted ship laden with cargo and a crew a ship owner might have been a little cautious. A ship that Henry would be in charge of was worth thousands of pounds. In the 18th century, the cost was largely dependent on where the ship was built, but about £20 per ton could be considered average for a fully equipped sailing vessel. An 1100-ton East India merchant ship for instance would cost about £22,000. A smaller vessel would be valued at about £4500, about £600,000 by today’s money, while the aforementioned East Indiaman would have been a whopping £2.8 million. Merchant ships were normally built for shipping companies supported by investments from shareholders. Crews were paid a percentage of the value of the sale of the cargo, while investors were paid a percentage based on the number of shares invested in the company.

Although Henry was licensed to captain a ship it seems that soon after receiving his Masters ‘ticket’ Henry took up a position on the John Norman as a Mate. This voyage began on the 16th of December in 1870. On board the John Norman, Henry appears to be the second highest-ranking member of the crew following the death of one Charles Hawke of yellow fever. Hawke was his superior for two months before the voyage ended. Yellow fever is spread by the bite of an infected mosquito and is usually found in countries along the equator. During the 18th and 19th centuries, yellow fever could cause a ship to be placed under quarantine, which meant that the ship would raise a yellow flag during the day and would shine a light at night until it was safe to enter the ports. In 1848, Edwin Montague, a passenger sailing to America from the Holy Land wrote “The abominable yellow flag, still marks our ship as ‘plague smitten. Every boat steers off from us, afraid of contamination.’ The John Norman returned home on the 25th of August the following year after an eight-month voyage. There is no record of Henry contracting this disease and the experience may have led Henry to believe that he was now more than capable of captaining his own ship. Henry, according to his son, ‘went to sea mostly in deep water vessels sailing mostly out of Cardiff in barques and big steamers’ It was whilst on his travels, either as a mate or a captain that Henry ‘got friendly with a Captain Symons of Braunton in Devon’ and it was Captain Symons invited Henry to his home for a holiday.

The village of Braunton in Devon lies just a few miles from the sea and the Taw-Torridge Estuary. South of the village is the River Taw that has made its way northwards from its origins on Dartmoor, its path changing direction until it reaches the neighbouring village of Heanton Punchardon and from there it flows south-west, diverted from its path by the aforementioned massive sand dunes of Braunton Burrows before it joins with the River Torridge, to form a tidal estuary that takes its name from both rivers. To the south of Braunton is Wrafton, a small hamlet that is separated from Braunton by a small field. This field was farmed by the family of Newcombe, who could trace their family to this part of the country to at least the 15th century. The present head of the family was Robert, a farmer and keeper of the local inn - the Exeter Inn (now the William’s Arms.) Robert Newcombe had been running this hostility for thirty years with his wife Mary with whom he had three children, Ellen, Henry and Emma.

Obtaining a position as a newly qualified captain would have been difficult, Henry had proved that he was capable on paper, however, actually entrusting Henry with a fine-masted ship laden with cargo and a crew a ship owner might have been a little cautious. A ship that Henry would be in charge of was worth thousands of pounds. In the 18th century, the cost was largely dependent on where the ship was built, but about £20 per ton could be considered average for a fully equipped sailing vessel. An 1100-ton East India merchant ship for instance would cost about £22,000. A smaller vessel would be valued at about £4500, about £600,000 by today’s money, while the aforementioned East Indiaman would have been a whopping £2.8 million. Merchant ships were normally built for shipping companies supported by investments from shareholders. Crews were paid a percentage of the value of the sale of the cargo, while investors were paid a percentage based on the number of shares invested in the company.

Although Henry was licensed to captain a ship it seems that soon after receiving his Masters ‘ticket’ Henry took up a position on the John Norman as a Mate. This voyage began on the 16th of December in 1870. On board the John Norman, Henry appears to be the second highest-ranking member of the crew following the death of one Charles Hawke of yellow fever. Hawke was his superior for two months before the voyage ended. Yellow fever is spread by the bite of an infected mosquito and is usually found in countries along the equator. During the 18th and 19th centuries, yellow fever could cause a ship to be placed under quarantine, which meant that the ship would raise a yellow flag during the day and would shine a light at night until it was safe to enter the ports. In 1848, Edwin Montague, a passenger sailing to America from the Holy Land wrote “The abominable yellow flag, still marks our ship as ‘plague smitten. Every boat steers off from us, afraid of contamination.’ The John Norman returned home on the 25th of August the following year after an eight-month voyage. There is no record of Henry contracting this disease and the experience may have led Henry to believe that he was now more than capable of captaining his own ship. Henry, according to his son, ‘went to sea mostly in deep water vessels sailing mostly out of Cardiff in barques and big steamers’ It was whilst on his travels, either as a mate or a captain that Henry ‘got friendly with a Captain Symons of Braunton in Devon’ and it was Captain Symons invited Henry to his home for a holiday.

The village of Braunton in Devon lies just a few miles from the sea and the Taw-Torridge Estuary. South of the village is the River Taw that has made its way northwards from its origins on Dartmoor, its path changing direction until it reaches the neighbouring village of Heanton Punchardon and from there it flows south-west, diverted from its path by the aforementioned massive sand dunes of Braunton Burrows before it joins with the River Torridge, to form a tidal estuary that takes its name from both rivers. To the south of Braunton is Wrafton, a small hamlet that is separated from Braunton by a small field. This field was farmed by the family of Newcombe, who could trace their family to this part of the country to at least the 15th century. The present head of the family was Robert, a farmer and keeper of the local inn - the Exeter Inn (now the William’s Arms.) Robert Newcombe had been running this hostility for thirty years with his wife Mary with whom he had three children, Ellen, Henry and Emma.

Ellen Newcombe was twenty years old, and in April of 1871 was in service as a servant to John and Louisa Cole, lodging housekeepers on the Quay in Ilfracombe. The Coles were elderly, and it was likely John had died and his wife was unable to manage the business herself and therefore Ellen was out of work, by the August of 1871, she was back home with her parents. In Cap’n Harry’s story of his parent's life, it is stated that Henry was introduced to Ellen. On the 15th of October in 1872, Henry and Ellen were married in the beautiful Church of St Augustine at Heanton Purchardon overlooking the River Taw.

Following their marriage, Henry and Ellen moved into a house on Barton Lane in Braunton, just over the fields from her family home. During the first few months of their marriage Henry may well have worked locally, sailing along the Devon coast, we know this because within three months of their marriage, Ellen was pregnant and their baby, a girl they called Minnie was born in the first week of October 1873. Five months after Minnie’s birth Henry secured what may have been his first position as a Captain. The ship was the Pownal. This first voyage was relatively short and his first sailing out of local waters into the ocean. Henry set sail on the 2nd March 1874 heading for the Azores, Spain and France and returned three months later at the end of April, but almost immediately he was made Master of the Constance and began a nine-month voyage to Brazil. It is likely that Henry did not return home to Devon, and in between these two trips, it is possible that he would not have seen his wife and their 18-month-old daughter until January of 1875. By the 2nd of February, Henry was, once again, heading out to sea as the captain of the Constance, this time his destination was China and Japan. As Henry left, he would not have known that Ellen was pregnant. Henry’s records at Lloyds of London show that he was still captain of the Constance in the spring of 1876, if this was the case he would not have known that Ellen had given birth to a son in October of 1875. Ellen named their son Robert Henry. It is likely that he may have seen him for the first time before he captained the Sir Galahad on a voyage to the Meditaraian, but if he did he was soon off again when he took charge of the Record in September of 1876. Henry can be found in London for two weeks in February 1877 while the Record was in Limehouse Dry Dock undergoing a survey. The work was completed in March and Henry and the Record set sail for France and the Gulf of Mexico. In the first months of 1878 and again in 1879, Henry was Captain of the Spartan heading on both occasions to Brazil. It is not known how many times Henry returned home to Braunton, but it must have been few, you can judge the length of time Henry and Ellen were apart in the infrequency of pregnancies - Ellen would not have another baby in the seven years following Robert's birth. Ellen’s life as a sea captain's wife goes unrecorded, but we know that women in her position did write to their husbands, so Henry may have known how his family were faring.

Ellen was no different from thousands of sailor's wives who stayed at home enduring years of absence and uncertainty, bringing up small children, managing domestic affairs and earning their living as best they could. Surviving letters held in the National Maritime Museum from women to their husbands reveal much about the experience of separation, interestingly, nearly all the letters are from husbands to wives rather than the other way around. In one way Ellen was lucky, she had her parents nearby who she could rely on. However, loneliness must have been an issue that may well have been discussed or even argued over when they were together.

In 1881 Henry was in Swansea in Wales boarding with Charles Newcombe, Ellen’s uncle who owned a warehouse in the town, but Ellen, Minne and Robert were still living with her parents at the Exeter Arms. It must have seemed ridiculous that they were separated by such a small distance, but as luck would have it, or perhaps it was fate that enabled the family to be together. Henry’s uncle William Samuel was having much the same issue, he was, as mentioned, part owner of the Par registered ship The Pedestrian, and in 1881 he was out at sea as captain and away from his family in the Purches’ hometown of Par. William, it seems, was a man of all trades, and as mentioned he had been an innkeeper and a steelworker, and at this point in his life it may have come to him that perhaps, captaining ships was a job he was not cut out for. Once back home William would pick up a contract to run a cargo of marble to Bristol from Italy, followed by picking up a cargo of coal in Cardiff to take home to Par and then from Par he was to take a cargo of china clay back to Italy. Not wishing to go back to sea he offered the contract to Henry. It was probably around this time that Ellen and the children made a move to Cardiff, and it was here, in 1884, that their daughter Emma was born. By 1891, the family had moved from Wales back to their home village and where Harry and Nellie were born.

Back home in Par, Henry may have thought that Ellen and the children would be settled, they had family here and no doubt had friends and Henry would hope that they would be happy. However, this happiness did not last long, within three years Ellen would be dead and Henry a widower with three children under the age of twelve, the youngest being just three. It was left to Minne, at just twelve, who ‘had to leave her situation’ to look after her younger brother and sister.' Henry’s feelings about this go unrecorded, but he would have coped with his loss by continuing with what he did best, which was seafaring. From this point, until the end of his life, Henry James continued to sail. There are no more official records of voyages to foreign ports, but Henry’s son recounts in some detail later trips to Newfoundland with his son Robert.

‘...they used to go to Newfoundland and load fish meal for the West Indies and South America, then load phosphates and hides and other cargoes for England and Germany. The small Newfoundland schooners used to trade to Portugal and Mediterranean ports, then ballast with salt from Cadiz or Oporto for Newfoundland again. When they arrived at St John's they might have orders to Fogo or Twillingate, two to three hundred miles down the Labrador coast to load. Some of the little ships used to make two or three voyages across the eastern ocean every year. They came home and do two cargoes of potatoes in bulk from the Scottish ports of Arbroath, Montrose or St Monance to the English Channel ports before fitting out for Newfoundland again. There used to be very small vessels trading to Newfoundland, being small they would always get a cargo where the larger ones would have to wait. There were several Jersey and Guernsey vessels carrying sixty to seventy tons of dead weight. We had a marvellous little vessel owned at Par carrying eighty tons called the Isabella, she used to make some record trips to Newfoundland, but she got wrecked after going into St Johns harbour. They used to have some terrible trips going out there, yet these men who sailed in them did not want to do anything else, those were the days when it was wooden ships and iron men, now it's iron ships and wooden men. My father was Master of the Isabella one year going to Newfoundland, she had a cargo of salt. On the way out she unshipped her rudder in mid-ocean. When the weather moderated they had to carry the salt from the after hatch to the forward hatch to put her by the head so as they could ship the rudder again. After a struggle, they managed to get shipped. Now it was get to work and carry the salt back aft again. They succeeded and got to harbour again. In those days there were no facilities such as radar to find your way around or radio to contact shore. It was all brain work and good seamanship’

The last record entry of Henry at sea was on the 19th of November 1903 on a two-month and three-day passage as captain of the Alfred.

‘...they used to go to Newfoundland and load fish meal for the West Indies and South America, then load phosphates and hides and other cargoes for England and Germany. The small Newfoundland schooners used to trade to Portugal and Mediterranean ports, then ballast with salt from Cadiz or Oporto for Newfoundland again. When they arrived at St John's they might have orders to Fogo or Twillingate, two to three hundred miles down the Labrador coast to load. Some of the little ships used to make two or three voyages across the eastern ocean every year. They came home and do two cargoes of potatoes in bulk from the Scottish ports of Arbroath, Montrose or St Monance to the English Channel ports before fitting out for Newfoundland again. There used to be very small vessels trading to Newfoundland, being small they would always get a cargo where the larger ones would have to wait. There were several Jersey and Guernsey vessels carrying sixty to seventy tons of dead weight. We had a marvellous little vessel owned at Par carrying eighty tons called the Isabella, she used to make some record trips to Newfoundland, but she got wrecked after going into St Johns harbour. They used to have some terrible trips going out there, yet these men who sailed in them did not want to do anything else, those were the days when it was wooden ships and iron men, now it's iron ships and wooden men. My father was Master of the Isabella one year going to Newfoundland, she had a cargo of salt. On the way out she unshipped her rudder in mid-ocean. When the weather moderated they had to carry the salt from the after hatch to the forward hatch to put her by the head so as they could ship the rudder again. After a struggle, they managed to get shipped. Now it was get to work and carry the salt back aft again. They succeeded and got to harbour again. In those days there were no facilities such as radar to find your way around or radio to contact shore. It was all brain work and good seamanship’

The last record entry of Henry at sea was on the 19th of November 1903 on a two-month and three-day passage as captain of the Alfred.

Henry spent nearly all of his adult life either at sea or hanging around ports, and at times frequenting the local inn or brothel. He did contract a venereal disease in his twenties, therefore it may be supposed that he liked his drink too. Henry recovered from the sexually transmitted disease, but his drinking caught up with him as the cause of his death is attributed to cirrhosis of the liver.

The sea shanty “What shall we do with the Drunken Sailor?’ was sung onboard sailing ships at least as early as the 1830s and is representative of the sailor staggering about drunk on more than his share of a tot of rum, we see this drunkenness as his fault, but it most certainly wasn’t. Drinking alcohol was a necessity on board a ship for survival, but it equally could be a way to blot out the brutality of life at sea. The sailor had to drink rum because water spoiled at sea and beer became undrinkable when kept in casks for long periods. So were sailors alcoholics? At the end of the 18th century, the daily ration in the Royal Navy was half a pint of neat rum twice a day. In 1740, it was proving to be a problem, Admiral Edward Vernon stated "The pernicious custom of the seamen drinking their allowance of rum in drams and often at once is attended with many fatal consequences to their morals as well as their health. Many of their lives shortened thereby, besides stupefying their rational qualities which makes them heedlessly slaves to every brutish passion." Did this apply to the merchant navy too I wonder? The ships that Henry James captained were vessels that carried as few as four crew members, larger schooners had five men, and the barquentines had seven crew, it would be risky and unsafe to drink to excess. Henry, I think was not an alcoholic in the true sense of the word, he was a man who in his career was presented with alcohol at every turn and who may later have been unable to function properly without it and having a brother and father in law who were ownersof a hostelry within walking distance might not have helped. Henry’s condition may have exhibited itself in fatigue, weight loss and swelling of his abdomen and legs, but they could have easily been seen as part of his advanced age. Eventually, though Henry James’ life came to an end.

At the age of seventy-six, on the 5th of April 1913, he died at his home in Grove Park Terrace where he lived with his three children.

The sea shanty “What shall we do with the Drunken Sailor?’ was sung onboard sailing ships at least as early as the 1830s and is representative of the sailor staggering about drunk on more than his share of a tot of rum, we see this drunkenness as his fault, but it most certainly wasn’t. Drinking alcohol was a necessity on board a ship for survival, but it equally could be a way to blot out the brutality of life at sea. The sailor had to drink rum because water spoiled at sea and beer became undrinkable when kept in casks for long periods. So were sailors alcoholics? At the end of the 18th century, the daily ration in the Royal Navy was half a pint of neat rum twice a day. In 1740, it was proving to be a problem, Admiral Edward Vernon stated "The pernicious custom of the seamen drinking their allowance of rum in drams and often at once is attended with many fatal consequences to their morals as well as their health. Many of their lives shortened thereby, besides stupefying their rational qualities which makes them heedlessly slaves to every brutish passion." Did this apply to the merchant navy too I wonder? The ships that Henry James captained were vessels that carried as few as four crew members, larger schooners had five men, and the barquentines had seven crew, it would be risky and unsafe to drink to excess. Henry, I think was not an alcoholic in the true sense of the word, he was a man who in his career was presented with alcohol at every turn and who may later have been unable to function properly without it and having a brother and father in law who were ownersof a hostelry within walking distance might not have helped. Henry’s condition may have exhibited itself in fatigue, weight loss and swelling of his abdomen and legs, but they could have easily been seen as part of his advanced age. Eventually, though Henry James’ life came to an end.

At the age of seventy-six, on the 5th of April 1913, he died at his home in Grove Park Terrace where he lived with his three children.

The view of an archetypal sailor is a man decked out in an outfit of black trousers, a hat, and a blue pullover maybe with an anchor on it. He has a pipe in his mouth and a repertoire of expletives and may be quick to temper. I don’t know what Henry was like, but I know that my grandfather remembered him as gentle, and who held his hand as they walked to the shops to buy sweets. He described him as short with a big white beard. He never told my grandfather of his life or the dangers he must have faced so there are no stories at all.

Henry James is a man I admire, at 5’ 4” and probably with a speech impediment, he managed to captain great sailing ships and sail the oceans of the world. What sights did he see, and what things did he experience that were not told through records and documents? I think I would have liked to have met him.