|

William Samuel Purches

1803 - 1861 |

The town of Portsea, where William Samuel was born in 1803, was an area immediately around the Royal Naval Dockyard at Portsmouth and was built as an 18th-century ‘new town’ in a time when England was prosperous. During this time homes were built outside the town walls, however, Portsea only occupied a small area, the remainder being farmland. As mentioned in earlier chapters, 19th-century housing spread across the south of the island, and from this, the seaside town of Southsea grew, its houses developed by architects such as Thomas Ellis Owen. This was a result of population growth. In 1795, there were 495 baptisms on the island compared to 1539 in 1800, in the same period there were 95 marriages compared to 634, and deaths numbered 305 in 1795 when there were 1363 in 1800. As you can see, in this fifty-year period, the population of the island had more than trebled and was, to use a modern term a boom town. Despite this, according to Alastair Geddes in his 1980 article Portsmouth during the Great French Wars, there were ‘dissatisfactions of seamen in the Navy, the struggle for the control of Portsmouth Corporation, and the attempts of the dockyard and other workers to protect their livelihood - although in many ways separate problems were also each of their problems of a rapidly growing and changing society.’ Within three years, however, not just the population of this tiny island, but the country as a whole, had much more to worry about - Napoleon was on the warpath!

William Samuel Purches was born on the 22nd of March, the sixth child of parents who were fast approaching their thirties. William’s baptism did not take place until over a month later. He was baptised at St Mary’s Church on the 8th of May. St Mary’s was the oldest on the island, and it was along the church path that William Samuel was carried to be formally welcomed into the Christian community. You can see St Mary's Church, with the vicarage on the extreme right, as it was at the time of William Samuel's birth.

The church font, around which the family gathered, has been dated to the 12th century. William Samuel, a baby born to a relatively poor family, would have been among hundreds of babies baptised with the water from this font. He would go on to live a better life than that of his ancestors, however, two men who were also baptised in the same font would achieve fame and fortune, one in the world of engineering and another in literature/social reform. The first of these men, Isambard Kingdom Brunel was born in the April of 1806 and baptised at the font on the 1st November. Brunel would go on to become "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history’ The second man to be baptised at the same font as my 3x great grandfather was Charles Dickens. Dickens was born in the February of 1812 and was baptised on the 4th of March. Dickens was a writer who was interested in the plight of the poor and helpless, and his writings reflect this. He made sure that sections of his stories were published in magazines so the poor could read them. By 1843, St Mary’s Church was deemed too small for a growing population and was pulled down and its medieval font eventually found a place in the church of St Albans in Copnor.

In the March of 1803, Britain declared war on France with the ending of a truce that had been signed nearly a year earlier - the Napoleonic Wars had begun. The civilian inhabitants of Portsmouth, knowing the importance of the Royal Navy Fleet, must have realised the consequences of this action, not only would the French hope to destroy the port, but they may well decide to invade the country. So much was the worry of a French invasion that large numbers of part-time soldiers were raised into volunteer units - a sort of nineteenth-century Home Guard. These volunteer forces were The Sea Fencibles, and in Portsmouth in the July of 1803, civilians were mustered in St George's Square. William Samuel's father, as far as I can ascertain, was not a member of the Royal Navy or the Marchant Navy, so there is a chance that he may have felt compelled to join this worthy cause. If this was the case, then men like Samuel were expected to exercise once a week and for this, they would receive a shilling, another bonus was that enrolment meant that they were exempt from impressment into the Navy. These volunteers provided services as a line of defence and prevented entry into the port by enemy shipping. The Sea Fencibles also acted as a coastguard service. By February 1810, the threat of a French invasion had passed, and the British Admiralty disbanded the units.

It is quite feasible that, as a boy in the seven William Samuel would have heard his father, a family member or family friends talking about the work done by this force, it may have had some influence on his later career in what was known then as the Preventative Water Guard. However, just like his grandfather and father, there are no references to tell us what he did in the years he grew from a boy to a man. We can only view his early life from what happening around him. In Portsmouth's Block Mills, in 1803, Marc Brunel's rigging blocks went into mass production, the first machines were installed two months before Williams Samuel’s birth. Forts, known as Palmerston Forts, were built around the town. In 1811, piped water was used on the island, but alas it was piped only to middle and upper-class homes! In 1812, Nelson’s flagship HMS Victory was decommissioned and there was a famous victory at Waterloo for Britain and its allies. These Napoleonic wars had raged for twenty-three years.

It is quite feasible that, as a boy in the seven William Samuel would have heard his father, a family member or family friends talking about the work done by this force, it may have had some influence on his later career in what was known then as the Preventative Water Guard. However, just like his grandfather and father, there are no references to tell us what he did in the years he grew from a boy to a man. We can only view his early life from what happening around him. In Portsmouth's Block Mills, in 1803, Marc Brunel's rigging blocks went into mass production, the first machines were installed two months before Williams Samuel’s birth. Forts, known as Palmerston Forts, were built around the town. In 1811, piped water was used on the island, but alas it was piped only to middle and upper-class homes! In 1812, Nelson’s flagship HMS Victory was decommissioned and there was a famous victory at Waterloo for Britain and its allies. These Napoleonic wars had raged for twenty-three years.

When the official end of the wars came with the signing of the Second Treaty of Paris in the November of 1815, William Samuel was twelve years old and just about to begin his life as an adult, still a child though, he would have had no real idea about the awful consequences of these wars. He would not know that the loss of life numbered between five and seven million, of which ninety-two thousand were members of the Royal Navy. He would not have known the monetary cost to the country was more than 1.5 million pounds in taxes and loans. Because of this, the country was faced with an economic slump, and high levels of unemployment, exacerbated by returning soldiers flooding the labour market and responsible, in part, for the Peterloo Massare in the north of the country four years later.

William Samuel's father, unlike the fathers of Brunel and Dickins, was not well off or educated and therefore not able to give his son a start in life that perhaps he would have liked to have done. His only option was to hope that William found him a position that meant he could stand on his own two feet. William went straight into a life at sea, he was the first of three generations to do so. Being a mariner meant that William was often away from home, sailing between different ports around the country, it was at some time between 1828 and 1829 that he sailed to the east coast of Cornwall, to the fishing villages of Newlyn, Penzance or Mousehole. It is in Mousehole, that I believe that he met his wife, Jane Pentreath. Jane was the daughter of fisherman Nicholas and Jane Pentreath whose home was in the village of Paul in Cornwall. There is no record of a marriage between the couple, and I am now wondering if they were married at all. It is a common thought that living together and not being married was a common occurrence during the Victorian era, however, a recent study shows that apart from a fraction of Victorian couples who shared a home, all had gone through a ceremony of marriage. Historians researching the subject of marriage in the 18th and 19th centuries tell us that cohabitation was very rare and that births outside marriage were also rare! Married or not William Samuel and Jane would go on to have five children, the first of them, a daughter Grace named after her maternal grandmother, was born in the May of 1830 and baptised in St Mary’s Church Portsea. It would seem that soon after their marriage William returned, with his family, to his home of Portsea in a house on Unicorn Road, a road leading to the Royal Dock Yard as seen in the image below.

Within a year Jane was pregnant again, and William was no longer employed as a mariner. Life at sea in the 19th century was a dangerous place to be, a sailor like William could be away from home for months, even years. For whatever reason, by 1832 William had taken up a position in the Preventative Water Guard - a service that would become the Coastguard service. How William went about getting this job is not known, members of this service were normally recruited from the Royal Navy, but this doesn't appear to be the case with William.

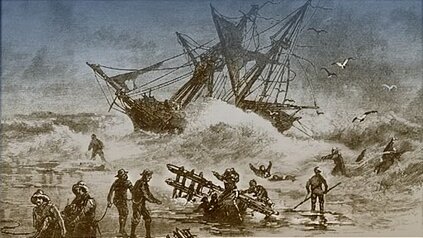

The history of the Preventative Water Guard officially began in 1809 when it was formed to operate in coastal waters with the aim of tackling smugglers who had managed to evade the revenue cruisers out at sea, and also to check that said cruisers were doing their job correctly, they would also be responsible for assisting when a ship had been wrecked.

The history of the Preventative Water Guard officially began in 1809 when it was formed to operate in coastal waters with the aim of tackling smugglers who had managed to evade the revenue cruisers out at sea, and also to check that said cruisers were doing their job correctly, they would also be responsible for assisting when a ship had been wrecked.

By 1816 the Preventative Water Guards were placed under the control of the Admiralty. Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars smuggling had reached epidemic proportions and was a serious problem as thousands of miles of the British coastline were unguarded and poorly policed, also smuggling was actually popular with people because goods were usually cheaper compared to what was legally available. On the whole, smuggling was not seen as a serious crime and local people supported the practice. More often than not, those who used the route across the Solent could land their goods without being noticed, however, landing contraband in and around Portsmouth proved difficult due to the large naval presence. Of course, smuggling still went on but how goods were landed was very different. Vessels were generally escorted into the port by naval vessels and once docked customs officers would board to prevent the cargo from falling into the wrong hands, but like any system, it was open to abuse, and corruption among the officers of customs and excise was not uncommon. By 1821, the service provided by the Water Guard was not just weakened by corrupt officers but also by simple logistics, the Water Guard were expected to work in different roles in separate areas, and this led to the service being inefficient, therefore in 1822, the service was taken out of the control of the Admiralty and placed under the Board of Customs. Records of those who worked in this area were almost non-existent and therefore there are no documents in reference to the start of William Samuel’s career.

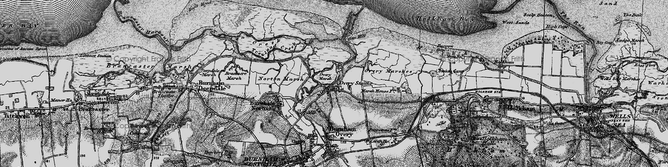

Men who took up a career in the coast guard service found that they were frequently transferred, and often these transfers took place precisely during the period when they were marrying, and their children being born. Couples often settled in the last place of appointment on retirement, many miles from their places of birth and this was true of William Samuel. His first posting, however, was to the East Coast of England and by April of 1832, William, Jane and Grace can be found living at Burnham Overy Staithe in Norfolk.

Men who took up a career in the coast guard service found that they were frequently transferred, and often these transfers took place precisely during the period when they were marrying, and their children being born. Couples often settled in the last place of appointment on retirement, many miles from their places of birth and this was true of William Samuel. His first posting, however, was to the East Coast of England and by April of 1832, William, Jane and Grace can be found living at Burnham Overy Staithe in Norfolk.

Just over sixty years before William and Jane arrived, ten-year-old Horatio Nelson had learned to sail among these tidal creeks, and within two years he had joined the navy. In 1805 in Portsmouth, when William Samuel was just two years old, Nelson had toured the aforementioned Marc Brunell’s newly opened block mills before boarding the HMS Victory and heading to his death at the Battle of Trafalgar.

When William, Jane and their new baby arrived at Burnham Overy Staithe, I wonder what they thought of the place. Jane would have been used to picturesque open harbours, and William an enclosed concrete naval fortification. Burnham Overy Staithe had a completely different outlook, it was isolated in a landscape of marshland, a place of cold winds and the strange calling of birds. Looking through the window of their new home, they would see a river dividing into tidal creeks and meandering through salt marshes, and in the distance, the murky water of the North Sea - this was Burnham Overy Staithe in 1830. It was not a village, just a few houses and buildings that were associated with the sea.

Along with the two coastguard houses, there was also a granary house, and boat house that may have doubled as a watch house with space where arms and ammunition could be stored and where in William’s time there would be muskets, bayonets, pistols, swords and powder. Smuggling had been a problem along this particular coastline for centuries, so much so that at one time soldiers from the Light Dragoon Regiment were drafted in to assist Customs and Excise officers in monitoring the area. These soldiers were billeted at the Pitt Arms (now the Hoste) in the neighbouring village of Burnham Market which was just a few miles from William’s home. There are plenty of tales of smuggling and the dangers faced by men like William from other parts of the county, but surprisingly little from Norfolk, maybe this was because the villages were few and far between and there was nowhere to hide the contraband, or maybe it was that the work of the Coastguard service had become more efficient.

Within a year of settling into their home Jane was pregnant, and it was in one of the cottages, with the black front, as pictured below that she would have given birth to her son William. Within another eighteen months, her daughter Elizabeth was born there.

Within a year of settling into their home Jane was pregnant, and it was in one of the cottages, with the black front, as pictured below that she would have given birth to her son William. Within another eighteen months, her daughter Elizabeth was born there.

Burham Overy is situated on the River Burn which runs past the parsonage that was the birthplace of Horatio Nelson and spreads out into the tidal creeks through the aforementioned salt marshes. Historically, Burnham Overy was a port that served the villages now known as The Burhams, where ships would dock. It was once a busy port with shipping links to the Low Countries, but the silting of the river caused trade to suffer and eventually trading moved downstream to Burnham Overy Staithe. In William’s time, the Staithe was accommodating schooners carrying up to 80 tons of goods with the most common commodity being corn and coal, with merchants stopping at ports all along the north Norfolk coast including Blakeney and Wells-next-the-Sea. With the toing and froing of schooners and the hustle and bustle of the port, Burnham Overy Staithe must have been a small, but lively community that was able to supply nearly everything that a family needed. From time-to-time Jane and the children would have made a trip to nearby Burnham Market, however, on a Sunday, the family would attend the church of St Clements at Burham Overy.

It was in St Clements Church that both William and Elizabeth were baptised, William in the April of 1832, and Elizabeth in the December of 1833. St Clements Church is unusual and not really very pleasing to the eye, but nonetheless, it is of interest because of its hotchpotch of designs. When William and Jane attended services only the nave was used as the church whilst the chancel became, among other things, a village school. The area beneath the church's tower arches had been blocked off in the centuries between the Reformation and the Victorian era, eventually, the two parts were reunited but still only connected by a narrow passage.

William Samuel spent just over five years monitoring the east coast of England, of his time there nothing is known, he may have gone about his tasks without complaint, but what of Jane’s time? She was at home alone with two small children and plenty of time to think, she must have worried about the dangers William faced while chasing down men whose sole purpose was profiting from smuggling illegal goods. Weatherwise, Norfolk was a different place from where she grew up, summers on the east coast can be pleasant, but in the winter months it can be pretty bleak, the view across the marshland out to sea was an ever changing palate of shades of grey. Who knows, maybe she liked it, but chances are she longed to be back in Cornwall, maybe it was her who initiated their next move? Whether by chance or design Cornwall was exactly where they headed next. However, what is more likely was the move was triggered by the silting of the Staith that made sailing into the port impossible, and/or the position of the coastguard was under review.

William Samuel spent just over five years monitoring the east coast of England, of his time there nothing is known, he may have gone about his tasks without complaint, but what of Jane’s time? She was at home alone with two small children and plenty of time to think, she must have worried about the dangers William faced while chasing down men whose sole purpose was profiting from smuggling illegal goods. Weatherwise, Norfolk was a different place from where she grew up, summers on the east coast can be pleasant, but in the winter months it can be pretty bleak, the view across the marshland out to sea was an ever changing palate of shades of grey. Who knows, maybe she liked it, but chances are she longed to be back in Cornwall, maybe it was her who initiated their next move? Whether by chance or design Cornwall was exactly where they headed next. However, what is more likely was the move was triggered by the silting of the Staith that made sailing into the port impossible, and/or the position of the coastguard was under review.

As Burnham Overy Staithe’s life as a busy port was coming to an end, the Cornish village of Par was just beginning. Wealthy mine owners and merchants were looking for new and bigger ports to ship their goods abroad, and Par, on the west coast of Cornwall was perfect. When the Purches’ arrived, in the first year of the reign of Queen Victoria, Britain was at the beginning of an industrial, political, and social change. This was also a time of empire, an empire that would grow from about two million to nearly twelve million square miles, this growth made Britain the most powerful trading nation in the world. The job of a Victorian coastguard was now more akin to a venue officer, and it was William’s job to detect and prevent attempts to evade the revenue laws in order that the country could prosper.

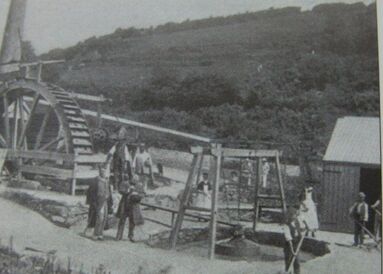

Par is situated within St Austell Bay, it has Polkerris to its west and Charlestown to its right. The bay itself has to the west a headland known as Black Head and to the east the larger headland known as Gribbens Head. Gribbens Head separates the bay from the port of Fowey and its estuary. By the beginning of the 19th century, Par had grown from a tiny coastal village with a small group of houses that overlooked the River Par, to a port serving the copper and china clay mines within the Luxulyan Valley. Initially a fishing village like its neighbour Polkerris, it soon developed into a community whose inhabitants were mostly employed in the mines in the aforementioned Luxulyan Valley. The growth of this village is credited to one man, Devon born Joseph Treffry. Treffry was a mine owner and industrialist whose acquisitions of a number of copper mines led to the building of smelting works and a harbour that was in use by 1833. William and Jane arrived in Par the year Treffry was expanding his business. In 1837 he purchased the pier and harbour of Newquay and three years later the harbour in Par was fully operational. The last improvement planned by Treffry, but completed after his death in 1850, was an extension of the railway along the canal bank to the harbour. Treffry’s interests lay in the extraction and the transportation of minerals, but there were other wealthy families in the area too, the Carlyon’s at Tregrehan, and the Rashleighs at Meanabilly were just two of them. Both these families were ancient, but they too, like Treffry, were profiting from Britain's expansion into the wider world.

The nearby port of Fowey was a bigger version of Par, but it had living there wealthy merchants whose interest lay in shipping, their ships sailed out of Fowey to places like Africa and China, it was their returning ships, whether they knew it or not that were carrying smuggled goods. In 1832, to counter this, the Admiralty decided that the Coastguard Service should be a reserve force for the Royal Navy and as a result, the regulations for recruitment of officers and men were laid down, and this coincides with William Samuel's first posting to Norfolk. As far as Par was concerned it appears there was no official monitoring of the coastline, William’s transfer then was the first step to establishing an official presence in the western part of St Austell Bay. The results of the 1841 census go some way to back this up, there were thirty-six families living in Par, twenty-six were miners, four were employed in connection with mining, and the other six families were employed in other work. Two families were agricultural labours, one was a yeoman, one an innkeeper, one a grocer, one a maltster, and there was William, the only coastguard.

It is my belief that William Purches was the first ‘official’ coastguard living in Par.

It is my belief that William Purches was the first ‘official’ coastguard living in Par.

William and Jane made their home in Par with their three children, Grace aged seven, William aged five, and Elizabeth aged two, it was likely however, that by the time they had settled into their new home Jane was already pregnant with their third child. Henry James was born in the February of 1837 and because there was not a church in Par, Henry was baptised on the 5th March 1837 at the church of St Blaise, the 15th-century church in the village of St Blazey just a few miles north-west of Par. Within two years Jane was pregnant again, and in the July of 1838 a daughter named Emma was born, she too was baptised at the parish church in St Blazey.

Emma’s baptism record states that William was employed as a Revenue Office - this entry confirms his official status.

Emma’s baptism record states that William was employed as a Revenue Office - this entry confirms his official status.

Smuggling was not an honest trade, but it was a lucrative one, and customs officers like William had to be aware of all the tricks that the wily smugglers used to avoid detection. Winston Graham in his series of books about the life of brave and honourable Ross Poldark, writes of smuggling in a romantic light. He describes the Cornish smuggler as “a clever fellow who knew how to cheat the government of its revenues and bring in brandy at half price”.

Once the office of the Custom and Excise had come under the control of the admiralty smuggling runs became impossible and the smuggler had to resort to a different tactic to bring the goods ashore. Smugglers resorted to all kinds of ways to get their goods past the revenue officers including dropping contraband overboard just close to the shore so their contacts could pick it up later, William would have had to sail along the shoreline with a grappling hook, called a Creeper, dragging it through the water until he found what he was looking for. He would have had what was called a Tuck Stick, a concealed 18-inch spike used to probe for illegal goods stowed among legal freight in a ship's hold. The coastguard was also aware that goods were not just smuggled from abroad, that it was a local problem too, boats called Coasters used false bulkheads and doctored water casks to hide their goods. Once ashore the smuggler was aided by local people who were quite willing to look the other way, and this is summed up in Rudyard Kipling wrote poem A Smuggler’s Song - ‘Them that ask no questions isn’t told a lie, Watch the wall, my darling, while the gentlemen go by’. Cornish antiquary, William Borlace was writing of this in 1758 ‘there is not the poorest family in any parish which has not its tea, its snuff, and tobacco, and (when they have money or credit) brandy’

Once the office of the Custom and Excise had come under the control of the admiralty smuggling runs became impossible and the smuggler had to resort to a different tactic to bring the goods ashore. Smugglers resorted to all kinds of ways to get their goods past the revenue officers including dropping contraband overboard just close to the shore so their contacts could pick it up later, William would have had to sail along the shoreline with a grappling hook, called a Creeper, dragging it through the water until he found what he was looking for. He would have had what was called a Tuck Stick, a concealed 18-inch spike used to probe for illegal goods stowed among legal freight in a ship's hold. The coastguard was also aware that goods were not just smuggled from abroad, that it was a local problem too, boats called Coasters used false bulkheads and doctored water casks to hide their goods. Once ashore the smuggler was aided by local people who were quite willing to look the other way, and this is summed up in Rudyard Kipling wrote poem A Smuggler’s Song - ‘Them that ask no questions isn’t told a lie, Watch the wall, my darling, while the gentlemen go by’. Cornish antiquary, William Borlace was writing of this in 1758 ‘there is not the poorest family in any parish which has not its tea, its snuff, and tobacco, and (when they have money or credit) brandy’

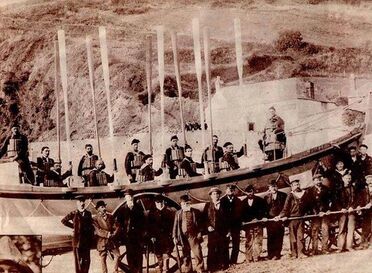

Beginning in the late 18th-century smuggling was no longer so profitable, the result of the government reducing tax on tea and other goods. By the mid-19th century, smuggling was on the decline, and this had a direct effect on William’s position. He had been employed as a coastguard in Par from 1837 to at least 1841 where he is listed as the only coastguard, however, the 1851 census shows no person employed in this capacity. By the April of that year, William was employed as a coastguard just a few miles along the coast at Polkerris where he was one of five other coastguards. If smuggling was not such a problem, why was there a need for so many men? The reason for this was that in 1856, after the end of the Crimean War, control of the Coastguard Service was once again transferred to the Admiralty and the coastguard took on more of a lifesaving role.

There was a lifeboat station in Polkerris as early as 1826, these men were concerned with the Fowey estuary and the toing and froing of ships into the port of Fowey itself but they did cover the western part of St Austell bay. The estuary at Fowey meant that it was impossible to launch a lifeboat that was powered by oars, it was particularly dangerous during storms, and a decision was made that a lifeboat station would be built on land at the top of the beach. This new station was built at a cost of £138 on land donated by the Rashleigh family. The first boat, named Catherine Rashleigh was delivered in the November of 1859. The station was named Fowey Lifeboat Station, a name that over the following fifty years caused some controversy, the name was changed three more times from Polkerris Lifeboat Station to Fowey and Polkerris Lifeboat Station and finally, it reverted back to its original title.

The census for the year 1861 was published the April, William was fifty-eight years old and still a coastguard and he seems in reasonably good health. However, within three months he would be dead. The cause of William's death is attributed to ‘chronic disease of the brain.’ One of the causes that could account for this is dementia, a condition that we have only recently begun to understand. A diagnosis in William’s time followed the onset of symptoms such as melancholia and mania and those suffering could find themselves in a lunatic asylum being deemed ‘mad.’ At fifty-eight, was William too young to be suffering from this? Another cause is a head injury (there is no mention of this on his death certificate) and depending on the injury it could have taken months before any symptoms surfaced, and as William was seemingly well enough in April and then dead months later, I feel a head injury might be the likely cause. Poor William, after over twenty years in an occupation where he met with danger square in the face nearly every day to lose his life in a tragic accident in a sleepy Cornish fishing village is so very sad.

William Samuel Purches had left the island of Portsea a relatively young man with a wife and a daughter and ended it, maybe tragically, still with his wife plus five children, and twenty-two grandchildren. He had served over thirty years as a coastguard, and during these years he had seen many changes. In his last years of employment, his role was less about apprehending the smuggler and more about wrecks, salvage, and lifesaving, it was an arduous life, and the sea a hard taskmaster and he had learned to respect it.

After thirty years in Hampshire and almost the same amount of time in Cornwall, I wonder which life he preferred?

After thirty years in Hampshire and almost the same amount of time in Cornwall, I wonder which life he preferred?

There are no family stories regarding the life of William and Jane to help out, these stories only begin with his son Henry.

William was laid to rest in the cemetery of the Church of St Andrew’s in Tywardreath.

William was laid to rest in the cemetery of the Church of St Andrew’s in Tywardreath.