|

Thomas Hendley

c 1435 - 1495 |

The time gap between the death of Gervais Hendley and the birth of Thomas Hendley was approximately one hundred and forty-five years, those years span the reigns of eight kings. In that time England had seen the murder of an anointed king, the usurpation of the throne, rebellion, the loss of France, and a violent and bloody family feud culminating in the end of one dynasty and the birth of another.

Thomas Hendley’s father's name was John but we know little about him, however, there are a number of references to a John Hendley in the Wills of Cranbrook cloth merchants at the time John was active. One reference that we know is Thomas's father can be found in an inventory that was taken by the clergy at St Dunstan's Church in Cranbrook on the 13th April in 1509.

‘iij copys of purpyll velewet one is velewette uppon velewet & an albe wt ij tewnykkys of the same colour & velewet uppon velewet wt Imagys brawderd of the geftr off Iohn hendely & he is grandefader to Gervase hendely of Cushhorne and Thomas hendely of Cranebroke strete.’

We can see from this that John was concerned with the fate of his soul, and that he was a man of some wealth and consequence. Despite that however, it would be his son and grandson who would set the Hendley family on the road to bigger and better things.

‘iij copys of purpyll velewet one is velewette uppon velewet & an albe wt ij tewnykkys of the same colour & velewet uppon velewet wt Imagys brawderd of the geftr off Iohn hendely & he is grandefader to Gervase hendely of Cushhorne and Thomas hendely of Cranebroke strete.’

We can see from this that John was concerned with the fate of his soul, and that he was a man of some wealth and consequence. Despite that however, it would be his son and grandson who would set the Hendley family on the road to bigger and better things.

Cranbrook’s broadcloth industry had grown steadily by the time of Thomas’s birth and many cloth making families had seen an increase in their landholdings, the Baker's, Courthope's and Lynche were three such families and it was Thomas’s generation who was the first to provide us with specific information about their specific landholdings. Thomas’s father’s will, if he made one, cannot be found and neither is there any information available to help ascertain the amount of land and property that was left to his sons, however, and as mentioned earlier, families in the County of Kent followed a system of inheritance known as Gavelkind, a concession which gave each son the right to receive an equal share of his father's land and property, this was different to the usual law of primogeniture where only the eldest son received the estate. Therefore it is highly likely that Thomas and his brothers received their lands via the aforementioned custom, and this, one would hope, would mean that the brothers felt that they were equals and this, in turn, made for a more secure family unit. On the other hand, it could cause major problems, whatever each son received and whether they were happy about it has been lost to history, however, the Manor of Coursehorn passed to my ancestor Thomas Hendley.

Thomas was one of five children, his three brothers were John, Robert and Richard and his sister was Agnes, the name of their mother is, as yet, unknown. Also unknown is the order of their births and the years in which they were born, although I suspect that it was probably around the 1430/40’s.

Thomas was one of five children, his three brothers were John, Robert and Richard and his sister was Agnes, the name of their mother is, as yet, unknown. Also unknown is the order of their births and the years in which they were born, although I suspect that it was probably around the 1430/40’s.

When Thomas was born the teenage King Henry VI was on the throne of England and Owen Tudor had made his way into Henry’s mother, the widowed queen Catherine of Valois bed, when Thomas was toddling his way around his Wealden home Catherine had given birth the Welshmen’s two sons - Edmund and Jasper Tudor, who as we know, would go on to change the course of history. Whether you were the offspring of a queen, a wealthy merchant or of peasant stock the custom for bringing up children was well established by the 14th century. When a mother gave birth it would be in her own home and she would have been attended by women, the birth was followed by baptism where the child was given a Christian name which usually reflected family tradition as we have seen with the Hendley’s who used the name Gervais at least five times. Official recording of births, marriages and deaths within a parish did not exist until 1538, so there is no way of knowing how often a specific name was used. These children grew up very quickly, if they were not employed in work around the house then they were out on the land, a younger child learning from its older sibling. Thomas and his three brothers were no different from any other medieval child, all three would have soon become familiar with the art of cloth making, an industry of which there is little information until the Tudor period. Any information in regard to how the Hendley’s business faired is gained from the study of wills and land grants, but none of these tell us the exact date that Thomas received Coursehorn, but what we can say is that if the John Hendley mentioned in documents in the early 1460’s is Thomas's father which I believe his was, then Thomas received his inheritance around the year he was married.

We know that the early Hendley’s were connected by marriage to one cloth-making family - the Bakers of Cranbrook, but it would be Thomas who was one of the first of the Hendley’s to marry out of the county, albeit just twelve miles away over the border in Sussex. Thomas's wife was Johanna Shoyswell of Shoyswell, a small manor that lies between the Sussex villages of Ticehurst and Etchingham.

We know that the early Hendley’s were connected by marriage to one cloth-making family - the Bakers of Cranbrook, but it would be Thomas who was one of the first of the Hendley’s to marry out of the county, albeit just twelve miles away over the border in Sussex. Thomas's wife was Johanna Shoyswell of Shoyswell, a small manor that lies between the Sussex villages of Ticehurst and Etchingham.

Johanna was the great granddaughter of Ralph de Shoyswell and daughter of William Shoyswell whose descendants were importers of salt right up to the early part of the16th century. The family connection, I believe, is two fold and lies in Goudhurst, a village just northwest of Coursehorn, and the granting of land in the manor of Whiligh and Wadhurst in East Sussex, to two families who held land there. These land grants were complicated and covered a period of over one hundred and fifty years, beginning in the reign of Edward III and ending in the reign of Edward IV. The name of Shoyswell can be found in early grants and is joined (in later documents by Hendley) by the Hordens, a family from Goudhurst, who frequently appear together in documentation in the 1420’s. These feoffments and indentures, which were concerned with the transfer of the above mentioned lands, began when one Robert de Pasley (Robert Passele) granted Whiligh to one of the aforementioned Goudhurst landholders, the Warde family of Ticehurst. In 1427 they in turn, granted their parcel of land to Ralph de Shoyswell and his wife Elizabeth -

"Thomas Warde of Ticehurst to Ralph Shoeswell & Elizabeth his Wife; Grant of the reversion of all the lands, which Johanna, wife of William Baker, his Mother, held for life in Ticehurst, except two pieces called Smythefeld & Orephetts, which William Warde his Grandfather had of Sir Robt. Passele, Knt."

Ralph and Elizabeth subdivided this parcel of land between their son Roger, and Elizabeth’s son from her first marriage to Thomas Playstede. In the years that followed, Roger’s portion passed to his son William, but by 1478 the Shoyswell portion of Whiligh had been granted to one William Saunders of Goudhurst. It seems that the Shoyswell’s still owned two parcels of land in Wadhurst called Mosehames, which in 1480 John, Johanna brother, subdivided between William Saunders, Edward Hordon and a John Hendley. However, inasmuch as these facts show us a definite connection between the families of Shoyswell and Hendley, it doesn't tell us anything about what Johanna brought to the marriage, but it at does go someway in explaining how a small piece of land in Sussex ended up as part of the Hendley’s estate. Nevertheless, Thomas Hendley's wife was Johanna Shoyswell and they were probably married at the time Henry VI was booted off throne of England and the handsome and charismatic Edward, Earl of March, took his place.

"Thomas Warde of Ticehurst to Ralph Shoeswell & Elizabeth his Wife; Grant of the reversion of all the lands, which Johanna, wife of William Baker, his Mother, held for life in Ticehurst, except two pieces called Smythefeld & Orephetts, which William Warde his Grandfather had of Sir Robt. Passele, Knt."

Ralph and Elizabeth subdivided this parcel of land between their son Roger, and Elizabeth’s son from her first marriage to Thomas Playstede. In the years that followed, Roger’s portion passed to his son William, but by 1478 the Shoyswell portion of Whiligh had been granted to one William Saunders of Goudhurst. It seems that the Shoyswell’s still owned two parcels of land in Wadhurst called Mosehames, which in 1480 John, Johanna brother, subdivided between William Saunders, Edward Hordon and a John Hendley. However, inasmuch as these facts show us a definite connection between the families of Shoyswell and Hendley, it doesn't tell us anything about what Johanna brought to the marriage, but it at does go someway in explaining how a small piece of land in Sussex ended up as part of the Hendley’s estate. Nevertheless, Thomas Hendley's wife was Johanna Shoyswell and they were probably married at the time Henry VI was booted off throne of England and the handsome and charismatic Edward, Earl of March, took his place.

In the first years of Thomas and Johanna’s marriage there was discontent among the Kentish people, there was a breakdown in law and order and there was a threat of civil unrest and a portion of the population blamed Henry’s government and those within his court. Election fixing, increased taxation and extortion added to the fact that Kentish weavers, like the Hendley’s, had already seen their incomes fall as a result of a slump in cloth sales, and lower incomes meant hunger and poverty and there were discussions about how this situation should not go on unchallenged, and just as the peasants under Wat Tyler had done in Thomas’s ancestor’s time, the people of Kent and Sussex gathered together to talk about a solution. Eventually, a list of grievances was drawn up and taken to London to be presented to the government. It should not be forgotten however, that the men of Kent who headed for London were loyal to their king, their issue lay with Henry’s ‘false councillors’’ men like Kentish landowner James Fiennes, Baron Saye. Many of those with a grievance were drawn from what is termed the ‘respectable’ members of Kent’s communities, like those in local government or those who upheld the law, others were men from families like the Hendleys who were worried about their livelihood and specifically the threat, issued by the aforementioned Baron Saye, that he would turn Kent into a wasteland in revenge for the murder of the William de la Pole, the Duke of Suffolk, whose headless body had washed up on beach in Kent.

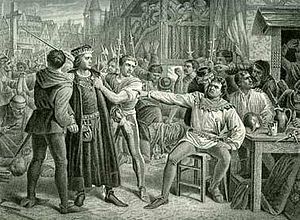

What history would call a rebel army arrived in Blackheath in mid-June, their leader, Jack Cade, attempted to come to some sort of agreement along the diplomatic route when he presented a petition listing twelve grievances, but these articles were dismissed and the conflict that followed came to be known as Cade’s Rebellion and it was one of the most important uprisings to take place in England since the Peasants Revolt some sixty-nine years earlier. The taking of London was a success for Cade, his forces had stormed the Tower of London but had failed to take control. Despite the violence, bloodshed and executions on London’s streets, pardons were offered and the rebels began their return journey home. There is no reference to any member of the Hendley family taking part in Cade’s Rebellion, I wonder if that was because they died a noble death on the streets of London fighting for the rights of the common man, their bodies unceremoniously discarded along with the rest of the dead heroes of that day. Their surname does not appear on the list of those pardoned either, therefore it is highly likely that they did not take part at all. However, they would have heard about the fighting from their neighbour’s and future kinsmen, John Roberts and his son who did take up arms, and they would have been alarmed when they heard that the king had come down hard on many in their local communities especially the execution, the following year, of four rebels in the village of Tenterden just six miles away. We know that the rebellion failed to change anything and ended with Cade’s execution following his capture by the corrupt and self-serving Kent landowner Alexander Iden.

The weakness of Henry’s reign and the effects of the Hundred Years War caused a serious slump in the broadcloth industry between 1440 and 1460 but it soon recovered, and an increase in demand for cloth in the local market and out of county saw to it that those in the business of cloth making would soon become prosperous, so prosperous in fact that the Hendley’s could afford to build themselves a brand new manor house. For the present however, the house in which Thomas and Johanna began their married life was a house on their manor now referred to as Little Coursehorn, this building was one of three on the manor. Others buildings were a house, now called Weavers End, a barn that Thomas’s family would convert into a cloth hall, more proof that the Hendley’s were fast becoming one of the wealthy families in the area.

The weakness of Henry’s reign and the effects of the Hundred Years War caused a serious slump in the broadcloth industry between 1440 and 1460 but it soon recovered, and an increase in demand for cloth in the local market and out of county saw to it that those in the business of cloth making would soon become prosperous, so prosperous in fact that the Hendley’s could afford to build themselves a brand new manor house. For the present however, the house in which Thomas and Johanna began their married life was a house on their manor now referred to as Little Coursehorn, this building was one of three on the manor. Others buildings were a house, now called Weavers End, a barn that Thomas’s family would convert into a cloth hall, more proof that the Hendley’s were fast becoming one of the wealthy families in the area.

Medieval clothiers like Thomas controlled and held an increasing share of the cloth trade, they were part of a select group of entrepreneurs that Edward Hasted called the “pillars of the kingdom who greatly enriched not only Kent but the nation in general… were a body to numerous and united, that at county elections, whoever had their votes and interest was almost certain of being elected.'' During the reign of Henry VII trade and industry were the backbone of England’s economy, woollen cloth made up 90% of the country’s exports. English wool was said to be the best in Europe. At the beginning of Henry’s reign, the export of raw wool had dropped by 40% and was replaced with the export of cloth. Henry was quick to capitalise on the growing importance of this industry, in 1485, just four months into his reign, he granted a charter to the town of Reading giving the mayor and burgesses authority to supervise cloth manufacture, therefore keeping an eye on the wealthy wool merchants and clothiers like Thomas who financed the whole broadcloth operation. The manufacture of broadcloth in the Weald was a domestic stand-alone industry, it received no support from other commercial sources nor did it receive funding from London, the city where much of the finished cloth was destined to be sold. The roots of this industry, as mentioned, lay in the inheritance of land and property, and Thomas held the Manor of Coursehorn but he also held land in Cranbrook and in the villages of Beneden and Tenterden. Thomas would have access to workshops and fulling mills, and we know from his will that he owned a shop in Cranbrook.

Thomas and Johanna had five children, two sons, John and Gervais and three daughters Agnes, Alice and Thomasine. All these children would go on to make good marriages within Cranbrook’s cloth making families. Agnes married Richard Baker, Alice married Edward Horden, Thomasine married Thomas Boys. Thomasine, like her father, was the only one to marry out of Cranbrook parish. Despite the fact that a medieval childhood was short, conditions hard and life expectancy short all Thomas’s children had children of their own - twenty-nine in total. Thomas’s extended family included the aforementioned brothers John and Robert and his sister Agnes, and between them they had nine children. This was Thomas Hendley’s family in 1472. That year would bring about the death of the first of his family, that of his elder brother John, who had died between November and December. John could not have been much older than thirty. He left a son named Thomas and two young daughters, Johanna and Alice and his wife Mercy pregnant with their fourth child. John Hendley’s Will makes provision for his soul, and secondly for his wife and children and thirdly, he puts aside land for his unborn baby if it be a son. Thomas, I believe was younger than his two sisters, he was possibly two years old in 1472, Johanna and Alice being aged about six and four respectively. The children were under age on the death of their father and John had taken this into account. Mercy, was granted all the estate for twelve years after which Thomas would inherit and would to hold his lands in fee simple, that is have full ownership of all properties and lands. Because of the children's ages the responsibility for their upbringing, their education, their arrangement of marriages and control of their lands were left hands of their uncles, Thomas and Richard would only relinquish this role once each child was married. John Hendley abided by the law of primogeniture by stating that if Thomas was to die and leave no issue then the lands would pass the next male heir which in this case was another John Hendley, his godson and cousin, I am yet to discover who exactly that is. All Johanna and Alice had to look forward to was a good marriage on which they were to receive twenty pounds each. John’s Will was proved on the 2nd December 1472. It was from that date that Thomas and Richard took up their responsibilities however, from that point we do not know how the family faired. Obviously, Thomas name appeared in his brother John's Will, but he only appears in a few other documents and they date to the late 1450’s and early 1460’s. He is listed as an executor in the Will of John Roberts of Glassenbury and is mentioned in documentation regarding a land grant relating to the aforementioned Roberts family and their manor of Boarzell in Ticehurst. He is named in the probate of his brother in law Richard Bigge. It is Thomas’s own Will however, that we gather most of our information about him and his landholding.

Thomas Hendley made his Last Will and Testament in the last half of 1495, the probate was dated to the 11th February 1496 and he was probably in his sixtieth year when he died. On his death Thomas Hendley landholdings were extensive, he held numerous lands Kent and Sussex, various properties including a cottage, a shop and a dyehouse and he also made a number of bequests that include 6s 8d to four friaries, one in Kent, one in Winchester and one in Rye. To a religious house in Combewell he leaves 20s. He leaves the total of 110s to eight churches in Kent and Sussex and to St Dunstan’s at Cranbrook he leaves gold and silver items, fabrics of velvet and damask cloth plus 20s to the parish priest and 6d to the clerk. He leaves monetary bequests to his three grandsons, and the sum of 10 marks to his granddaughter on her marriage. The remainder of his land and property is divided between Johanne his wife and Gervais his younger son. All of his land and property is left to his wife “...all the same for her life provided my said wife shall honestly find Gervais, William and Thomas sons and heirs of John Hendley my son during the term of her life (then to be divided as per his wishes)” To Gervais he leaves his Manor of Coursehorn and ten other parcels of land. Also, on the death of Johanne, Gervais is to receive all lands in the villages of Beneden and Tenterden. Thomas leaves nothing to his eldest son John, the father of the aforementioned grandchildren, all property and lands that should have passed to John were left in the care of their grandmother and as you have seen the division of said properties, after Johanna's death, was already set out. So what of John? There is no reference to his death in other documents, and he’s not mentioned as ‘my son John now deceased’ in Thomas’s Will, he is also not mentioned in Johanna Will following her death in 1509. So was John the black sheep of the family? Was he as wastral who couldn’t be trusted with money? Thomas seems to think so, is this why he was protecting his grandson’s inheritance? Thomas’s Will does make interesting reading, it is a fine example of the division of property in the favour of the eldest child in this case Thomas, the elder of the grandsons who received £100 (nearly £67,000 in today's money) whilst William and Gervais get ten bales of wool each! What is also interesting is the fact that he leaves the ancient manor of Coursehorn to his younger son Gervais and not to the elder grandson. We will never know the reason for John’s exclusion just as we don’t know the cause of Thomas’s death, we do know that he wished to be buried in the Church of St Dunstan’s in the south aisle before St Thomas and that he provided a fine cloth of velvet with embroidery of gold in the shape of crucifix in the middle and two images of Mary and John as a covering for the altar.

Thomas Hendley's Last Will and Testament, not only gives us an insight into the makeup of the family, but it gives us our first glimpse of Cranbrook in the last quarter of the 15th century when England was in the midst of a great turmoil and a time history would refer to as the Wars of the Roses. During this time four Hendley brothers had laid the foundations of their small dynasty, Edward IV was king of England and he had taken the throne for a second time, the mighty Kingmaker was dead, run through with a sword at the Battle of Barnett and his daughter Anne had made a dynastic marriage that would, some eleven years later, make her queen of England.