|

Gervais Hendley

c1302 - c1344 |

According to Dr Michael Zell in his Industry in the Countryside: Wealden Society in the Sixteenth Century, there were at least four cloth-making families who lived in and around Cranbrook in the 15th century, one of them was the Hendley’s. He notes that they were (by the 16th century) extensive landholders and only two of the four families include a father and son partnership, he doesn’t include Thomas Hendley, my 16th great grandfather in that category despite the fact that he worked with, and left his estate to his son Gervais. However, it cannot be said that the descent of the manor of Coursehorn through the Hendley’s in years from 1302 to c 1445 passed from father to son, because the names of those who lived at that time are lost, however, the Hendley family progenitor was Gervais Hendley, a man who may have been my 21st great grandfather. Gervais was the first of the Hendley’s whose name we know because he was the first to appear in official documents. He was born during the reign of Edward II, a time when royal favourite Piers Gaveston joined the royal court and the time of the disappearance of Edward II in 1327. By the time of the coup d’etat by Edward’s queen and Roger Mortimer, Gervais had a wife and family.

Gervais Hendley’s manor of Coursehorne was triangular in shape and was bordered on its western side by Cranbrook. To its north, south and eastern side were the manors of Sissinghurst, Beneden and Golford respectively and it probably measured no more than half a mile in each direction being made up of a few fields with a small house, a couple of pigsties, a barn and maybe a chicken shed! The Hendley’s were first and foremost sheep farmers, the grassland sustained the breeding and grazing of sheep who produced quality wool. Most landholders like Gervais made a living from farming alone and subsidised their income from money made in weaving. Weaving was done in the home on a narrow loom or in a purpose-built building and was usually performed by men, however, the first stage in cloth production was the spinning of the wool and this was the responsibility of the females in the family. Despite the fact that spinning is an ancient occupation, the spinning wheel, which we usually associate with this process had not yet arrived in England, therefore we would find a medieval women using a spindle and a distaff - a long piece of carved wood held horizontally that was designed to hold un-spun fibres that kept them untangled.

In the early part of the 14th-century cloth that Gervais produced was primarily for his own use, however this was about to change. King Edward III was determined to boost this embryonic cloth industry by encouraging skilled artisans from northern Europe to settle in England. Edward, it has been said, favoured the area around Cranbrook and granted Flemish craftsmen, who settled there, royal protection. Letters patient in regard to this can be found as early as 1331 in the Calendar of Patent Rolls. Production of woollen cloth in England would become the mainstay of the medieval English economy, so much so that it would be described as the ‘jewel in the realm’. In fact, wool was so important to the country that the king ordered that his chancellor should sit on a woolsack, a large bale of wool covered in red cloth. This tradition continues today, the Speaker in the House of Lords sits on what is called a Woolsack - a large red square cushion.

The growth of the cloth industry in Cranbrook grew steadily, but it did not bring Gervais Hendley the riches it brought later generations, it would be his 15th and 16th century descendants who would reap the benefits, but he can be credited as one of the founding families in this fledgling industry. Within ten years of Edward III’s invitation to the Flemish weavers, Gervais had moved one step up the social ladder, and we find him teetering between the peasantry and those who would today we would call middle class. Gervais, it seems, was a man with some influence in the community and on the 6th April in 1344 we find him appearing as a juror on an inquisition regarding the neighbouring manor of Buckhurst, recently held by the deceased Richard Handlo who had died on the 15th December the year before. To be asked to sit on a jury, Gervais would have had been forty-two years of age or over and have a good knowledge of the local area. From this document, it can be established that Gervais was born no earlier than 1302, however, after 1344 we hear no more of Gervais, we don’t know his wife or how many children he had nor do we hear of any other members of the Hendley family in later generations. It is not until 1472 that we meet brothers John, Robert and Thomas Hendley, the latter being my 16th great-grandfather.

It would appear that there are at least four generations that divide Gervais and the aforementioned three brothers, if Thomas was directly descended from Gervais, which I think he was, and taking into account the different inheritance system in Kent, then Gervais Hendley was probably Thomas's 3x great grandfather. So what happened to the Hendley’s in the intervening years? Most of them go unrecorded because they are of no historical significance, they simply were born, they married and they died! Some died of natural causes, maybe some died fighting in the Hundred Years War. It may be that Gervias succumbed to the terrible disease known as the Black Death in one of the six outbreaks between 1350 and 1402 after being infected by a bite from something as tiny as a flea. It is not pleasant to think that some of my ancestors may have died from a horrible death that involved fever and black swellings in their neck, armpits and groins! Once the buboes appeared the infected person would be dead inside six days!

An account of this plague in Kent survives in the writing of William of Dene, a monk of Rochester.

‘In this year a plague of a kind which had never been met with before ravaged our land of England. The Bishop of Rochester, who maintained only a small household, lost four priests, five esquires, ten attendants, seven young clerics and six pages so that nobody was left to serve him in any capacity. At Mailing, he consecrated two abbesses but both died almost immediately, leaving only four established nuns and four novices. One of these the Bishop put in the charge of the lay members and the other of the religious, for it proved impossible to find anyone suitable to act as abbess. To our great grief, the plague carried off so vast a multitude of people of both sexes that nobody could be found who would bear the corpses to the grave. Men and women carried their own children on their shoulders to the church and threw them into a common pit. From these pits, such an appalling stench was given off that scarcely anyone dared even to walk beside the cemeteries.’

‘In this year a plague of a kind which had never been met with before ravaged our land of England. The Bishop of Rochester, who maintained only a small household, lost four priests, five esquires, ten attendants, seven young clerics and six pages so that nobody was left to serve him in any capacity. At Mailing, he consecrated two abbesses but both died almost immediately, leaving only four established nuns and four novices. One of these the Bishop put in the charge of the lay members and the other of the religious, for it proved impossible to find anyone suitable to act as abbess. To our great grief, the plague carried off so vast a multitude of people of both sexes that nobody could be found who would bear the corpses to the grave. Men and women carried their own children on their shoulders to the church and threw them into a common pit. From these pits, such an appalling stench was given off that scarcely anyone dared even to walk beside the cemeteries.’

The Bubonic Plague was one of the most devastating pandemics in history, between 75 and 200 million people across Europe are said to have died in the years 1346 to 1353. Not only was it a major setback to society but thirty years later the country had still not recovered from its effects, workers were few, jobs were many, the treasury was empty and in an effort to counter this taxation was increased. This new tax angered the poor, for they had come to enjoy their 'freedom' and to a certain extent they had gained the ability to control their own lives. In 1380, to rectify the situation, a poll tax to raise money to help England financial situation was introduced that would initially result in the nonpayment of taxes but escalate into violence and death and the event what history calls the Peasants Revolt. Rebels from Kent, led by Wat Tyler, marched to London to talk to England’s king, the fourteen year old Richard II.

On the 30th June 1381 Richard granted concessions to the rebels and issued charters, but within fourteen days had retracted them. It was during these two weeks that Flemish weavers and cloth making entrepreneurs like the Hendley’s were targeted, the reasons for this has not been fully explained but it may be that the root of all the anger lay in economic rivalry. After 1381 the institution of serfdom was in decline and gradually what these men demanded they received. The peasants were not the only ones who had to adapt, members of the aristocracy and the landed gentry had to do so too. At this time we find marriages taking place between the gentry and those in the merchant class, the Hendley’s too would find themselves marrying into a class of people that were once above them. Along with the changes in society came a change in the distribution of wealth, and again the main factor behind the growing wealth, particularly in the south of the country was the expansion in cloth-making.

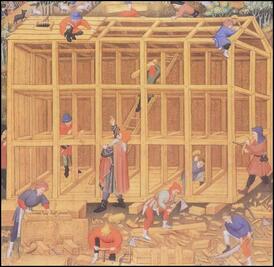

It is unknown how many families in Cranbrook and the surrounding manors lost members to the Black Death but those landholders who did survive would have quickly seized upon the chance of taking over the vacant holdings of those who didn't. Landholders at this time are known to have increased the size of their farms from forty to fifty acres. If this was the case with Gervais Hendley then, as previously mentioned, this would have enabled him to graze more sheep and customise their buildings to suit his needs. With money earned came the opportunity to spend it and this can be viewed in the increase in house building. New timber-framed houses were built in Sussex and Surrey, and in Kent what is known as a Wealden House began to appear.

On the 30th June 1381 Richard granted concessions to the rebels and issued charters, but within fourteen days had retracted them. It was during these two weeks that Flemish weavers and cloth making entrepreneurs like the Hendley’s were targeted, the reasons for this has not been fully explained but it may be that the root of all the anger lay in economic rivalry. After 1381 the institution of serfdom was in decline and gradually what these men demanded they received. The peasants were not the only ones who had to adapt, members of the aristocracy and the landed gentry had to do so too. At this time we find marriages taking place between the gentry and those in the merchant class, the Hendley’s too would find themselves marrying into a class of people that were once above them. Along with the changes in society came a change in the distribution of wealth, and again the main factor behind the growing wealth, particularly in the south of the country was the expansion in cloth-making.

It is unknown how many families in Cranbrook and the surrounding manors lost members to the Black Death but those landholders who did survive would have quickly seized upon the chance of taking over the vacant holdings of those who didn't. Landholders at this time are known to have increased the size of their farms from forty to fifty acres. If this was the case with Gervais Hendley then, as previously mentioned, this would have enabled him to graze more sheep and customise their buildings to suit his needs. With money earned came the opportunity to spend it and this can be viewed in the increase in house building. New timber-framed houses were built in Sussex and Surrey, and in Kent what is known as a Wealden House began to appear.

The typical Wealden house evolved from the Anglo-Saxon aisled hall, it had an open hall with a central fire and jetted end bays, this design would remain relatively unchanged for over five hundred years. There is no evidence of a house such as this at Coursehorn, the earliest buildings on the Hendley’s manor dates to the late 15th century, therefore, the exact whereabouts of Gervais’s Wealden House is not known, but it is possible that it stood on the site of a 15th-century building that is now called Little Coursehorn - Gervais’s descendent would later build themselves a fine moated manor house just a hundred yards further north.

So who did live at Coursehorn in the 145 years between the death of Gervais and the birth of my 16th great grandfather? We will never know that of course, and neither will we establish the exact connection. Naming patterns are an aid and Gervais is a family name, it was used at least three times in two generations, but the most important factor in determining a direct line between generations would be the inheritance of land and property, and this was usually granted to the eldest son, however, as mentioned previously, the County of Kent used the law Gavelkind when dealing with inheritance. Although it is likely that Thomas Hendley was Gervais’s three times great-grandson, he is not necessarily descended through the eldest son of each generation.

It is not known whether it was a gradual process or a conscious decision by the Hendley family to make the transition from sheep farmer to medieval clothier, but we know they did and Gervais’s descendants would add the tasks of dyeing, fulling and shearing to the process of cloth making. Woollen cloth would be classed as a luxury item, Gervais’s Tudor namesake could charge up to 10 shillings a yard for it, and thanks to those unknown 14th century Hendleys the family would have both skills and the resources to make their fortune in this industry.

It is not known whether it was a gradual process or a conscious decision by the Hendley family to make the transition from sheep farmer to medieval clothier, but we know they did and Gervais’s descendants would add the tasks of dyeing, fulling and shearing to the process of cloth making. Woollen cloth would be classed as a luxury item, Gervais’s Tudor namesake could charge up to 10 shillings a yard for it, and thanks to those unknown 14th century Hendleys the family would have both skills and the resources to make their fortune in this industry.