In the middle of the eighteenth century, when my Mitchell family farmed their small piece of Cornwall, the county was as remote as it was in the middle ages. Cornwall was still was a county apart.

In the rest of the England, the Industrial Revolution saw the beginnings of a new way of life, but Cornwall was too distant for these changes to make an immediate difference, there were few roads that were suitable for carts let alone the new stage coach that was becoming fashionable elsewhere, so the majority of the populace rarely traveled away from their place of birth.

Cornwall's inhabitants continued to pursue their old way of life, speaking their own distinctive language, celebrating their festivals and listening to the stories of Cornish giants and piskies, but this was soon to change. The old, well traveled routes from Truro to Launceston, Camelford and Lostwithiel were set to improve beyond all recognition, and by the end of the eighteenth century, the new eight horsed stage coaches would soon be arriving which could take the Cornish gentry out of Cornwall to London in less than three weeks.

Mining in Cornwall had reached its peak by the nineteenth century, foreign competition saw to it that Cornish ore, such as tin and copper, became unprofitable and Cornwall once again was reliant on goods that were produced on it lands and this of course would benefit those who owned and worked on it.

It was into a Cornwall, still very much set in its ways, that my 4x great grandfather, William Mitchell was born.

In the rest of the England, the Industrial Revolution saw the beginnings of a new way of life, but Cornwall was too distant for these changes to make an immediate difference, there were few roads that were suitable for carts let alone the new stage coach that was becoming fashionable elsewhere, so the majority of the populace rarely traveled away from their place of birth.

Cornwall's inhabitants continued to pursue their old way of life, speaking their own distinctive language, celebrating their festivals and listening to the stories of Cornish giants and piskies, but this was soon to change. The old, well traveled routes from Truro to Launceston, Camelford and Lostwithiel were set to improve beyond all recognition, and by the end of the eighteenth century, the new eight horsed stage coaches would soon be arriving which could take the Cornish gentry out of Cornwall to London in less than three weeks.

Mining in Cornwall had reached its peak by the nineteenth century, foreign competition saw to it that Cornish ore, such as tin and copper, became unprofitable and Cornwall once again was reliant on goods that were produced on it lands and this of course would benefit those who owned and worked on it.

It was into a Cornwall, still very much set in its ways, that my 4x great grandfather, William Mitchell was born.

Lying just one hundred and forty metres from Trevemper, and still in place today, is a square stone slab that formed the base of a medieval wayside cross that once stood at the centre of an ancient road junction. During William’s lifetime, it maybe that the whole of the cross would have been visible, the family would have passed by it on a daily basis, their carts filled with the fruits of their labour.

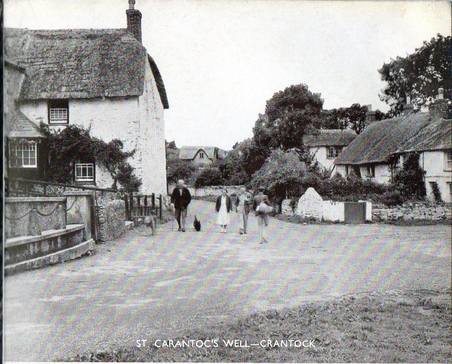

The cross that William would have seen could have been circular in shape with an incised cross as pictured, or in the shape of a wheel. Wayside crosses appeared in England between the ninth and fifteenth centuries, not only as a reminder to the traveller of their faith, but as a mark of reassurance as they journeyed in what must have been difficult terrain. The existence of this cross base at Trevemper, demonstrates that this area was an important route the medieval traveller was using to reach the Collegiate Church of St Carantoc, founded in the mid thirteenth century by Bishop William Briwere. This settlement at Crantock was in existence as early as the year 460, its name originating from the term, the "dwelling of monks". Today, it is a quaint and pretty seaside village much adored by locals and frequently visited by the twenty first century visitor.

The villages that surround Crantock are Newlyn East, St Columb and Cubert and William Mitchell could well have hailed from any one of these, but it is more than likely that his place of birth was Crantock. Families with the surname of Mitchell were prolific in this area, and there was a prevalence of intermarriage between the inhabitants of such small communities that were only accessible to the outsider from the sea, ancient road systems or coastal paths, so it is no big surprise that William Mitchell’s wife had an identical surname. She was Peggy Mitchell.

Nothing of William’s life, until his marriage, is known, so Williams story begins here.

The marriage of William to Peggy took place on the 22nd of November 1788 in Crantock Parish Church when William was twenty one years old, but it was not until 1797 that the couples first child is born, a girl they name Elizabeth. Following Elizabeth’s birth, Peggy went on to have a child every two years until 1814, from this we see that Peggy could conceive quite easily, so the reason why the first ten years of William's marriage was childless, is a mystery. It is unlikely that there were no children born to the couple in that time, but there are no birth, baptisms or death records of any children before this date to prove it. So why were the couple childless until the birth of Elizabeth? The first thought must be that William and Peggy were living elsewhere or maybe these children's existence has gone undocumented and they have faded into history unnoticed. Maybe they died in infancy or early childhood, maybe their baptism records have been lost, Elizabeth’s baptism record cannot be located and it is not until the births of two more children that we find any Mitchell children in the Crantock Parish records at all. The census records for the next forty years show that none of William's children ventured far, the closeness as a family and the way they interacted with one another makes me think there was a significant event that precipitated this outcome. Brothers and sisters, grandchildren, great grandchildren, nieces and nephews are all linked directly with each other, they can be found living in one another's homes. There is not one child that cannot be placed within this large family unit in nearly a decade, there are no children unaccounted for !

There is nothing to prove that any ‘older’ children ever existed and there is no answer as to why.

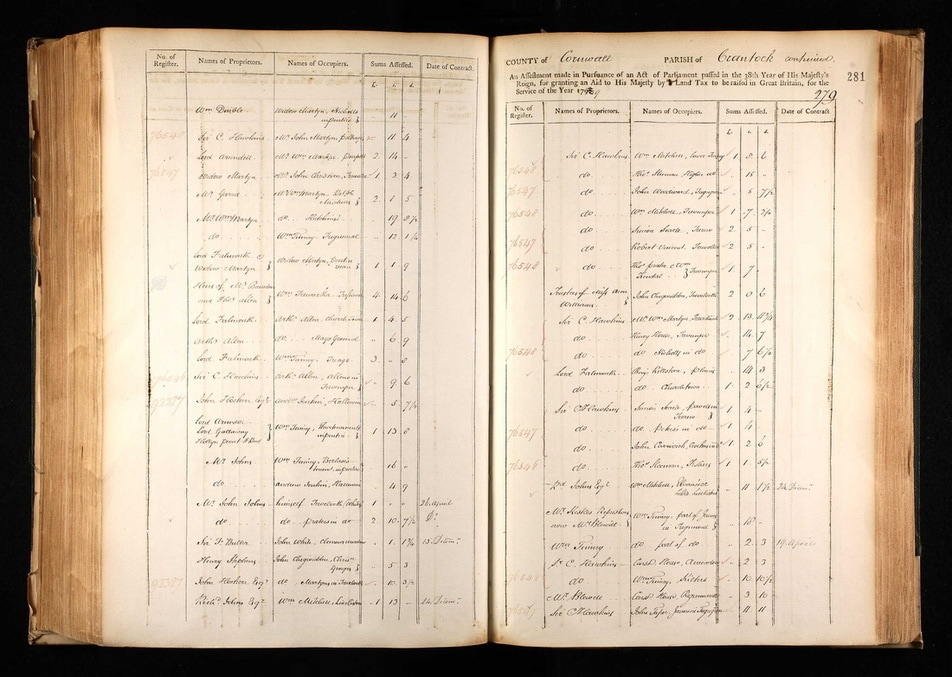

William's life as a farmer begins in the year 1799, when his name appears in the Land Tax Returns Book for Crantock, William is farming the lands of Richard John’s Esq. at Lescliston and at Little Lescliston. William also appears in the same book farming lands of Sir Christopher Hawkins at Lower Treringy and Trevemper.

Nothing of William’s life, until his marriage, is known, so Williams story begins here.

The marriage of William to Peggy took place on the 22nd of November 1788 in Crantock Parish Church when William was twenty one years old, but it was not until 1797 that the couples first child is born, a girl they name Elizabeth. Following Elizabeth’s birth, Peggy went on to have a child every two years until 1814, from this we see that Peggy could conceive quite easily, so the reason why the first ten years of William's marriage was childless, is a mystery. It is unlikely that there were no children born to the couple in that time, but there are no birth, baptisms or death records of any children before this date to prove it. So why were the couple childless until the birth of Elizabeth? The first thought must be that William and Peggy were living elsewhere or maybe these children's existence has gone undocumented and they have faded into history unnoticed. Maybe they died in infancy or early childhood, maybe their baptism records have been lost, Elizabeth’s baptism record cannot be located and it is not until the births of two more children that we find any Mitchell children in the Crantock Parish records at all. The census records for the next forty years show that none of William's children ventured far, the closeness as a family and the way they interacted with one another makes me think there was a significant event that precipitated this outcome. Brothers and sisters, grandchildren, great grandchildren, nieces and nephews are all linked directly with each other, they can be found living in one another's homes. There is not one child that cannot be placed within this large family unit in nearly a decade, there are no children unaccounted for !

There is nothing to prove that any ‘older’ children ever existed and there is no answer as to why.

William's life as a farmer begins in the year 1799, when his name appears in the Land Tax Returns Book for Crantock, William is farming the lands of Richard John’s Esq. at Lescliston and at Little Lescliston. William also appears in the same book farming lands of Sir Christopher Hawkins at Lower Treringy and Trevemper.

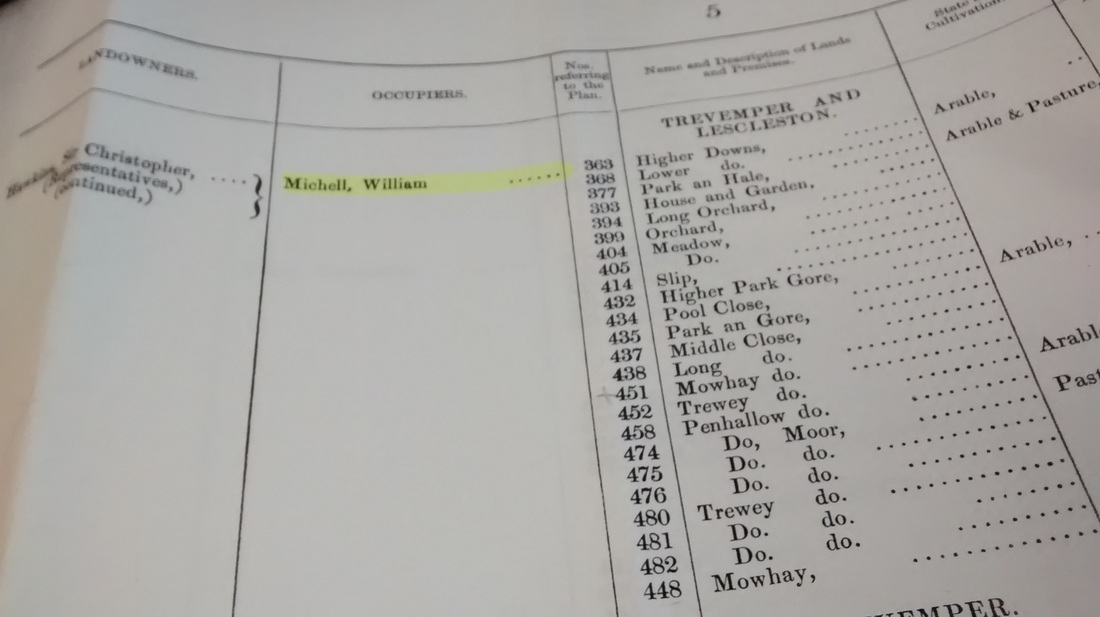

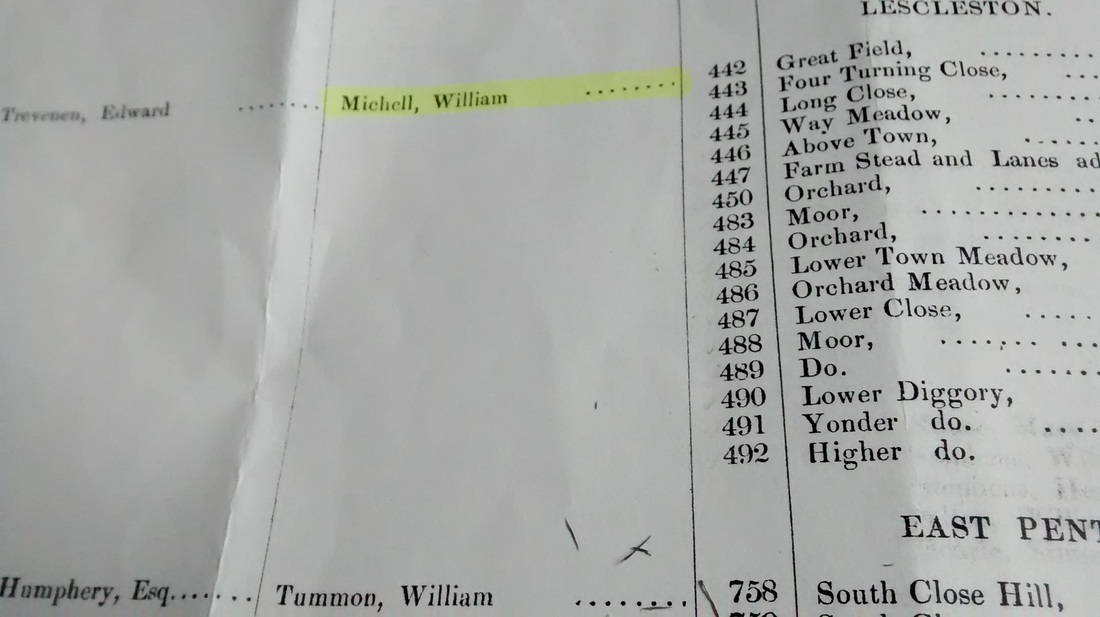

The land tax was first introduced in 1692 to raise revenue by taxing personal estates, public offices and land. It lists landowners and their tenants and as we have seen William is listed as farming four areas. Settlements in Cornwall consisted of small hamlets, such as those previously mentioned, and like Trevemper, included a farm and a mill, but no church. These farms were small, their acreage could range from ten to as much as ninety that were bordered by large grassed hedges. The 1799 tax records do not tell us anything about the land itself. However, tithe maps for 1839 do and we can see from the two images below exactly what William was farming at Lescliston and Trevemper.

Lower Treringy, Lescliston and Trevemper lie under half a mile from each other, bordered to the north by Newquay, to the east by the village of Quintrell Downs, to the south by a large area of arable land known as Newlyn Downs and to the west by the blue seas of the Atlantic. Running through the community is the River Gannel on which the livelihood of the Mitchell family was, in some ways, dependent. As the river meanders its way through Newlyn Downs, and makes its way north towards the coast, it passes firstly Lescliston and secondly Trevemper, with its mill, its farm and its grade II listed bridge, a bridge that William and his descendants would have crossed and recrossed for over a hundred years.

In the seventeen years following the birth of Elizabeth, William became a father to seven more children. James in 1799, Johanna in 1803, Ann in 1805, Josepha in 1807, Susanna in 1808, Samuel in 1811 and finally Joseph in 1814. William had three strong sons to help him on the farm so it would be unlikely, except possibly at harvest time, that he needed to employ any full time labourers and what William grew on his farm was dependent on what type of soil he had. Cornish soil ranged from a sand/silt mix, to heavy clay, either was a challenge for any farmer as he trudged behind a horse drawn plough from dawn to dusk. Cornwall's climate was not such a demanding task master, a longer growing season and fewer sharp frosts made life a little bit easier for William than it would his contemporaries way up north. William may have grown some sort of cereal, by the time he had taken over Lescliston the turnip was becoming a popular crop in England, but because it reduced the lime in the soil, the Cornish farmer grew less of it. He may have kept a few sheep and a couple of cows. Life for Peggy along with their four daughters was busy too, in the spring and summer they would have grown herbs such as mint, lavender, rosemary and parsley and used them not only as flavouring for food but in medicinal remedies. The farm at Trevemper had a kitchen garden and an orchard where the women could grow vegetables such as beans and peas. In the late summer and autumn, Peggy and her children would have harvested, dried and stored their fruits and vegetables for winter meals, maybe making soap with leftover fats, adding lavender as scent.

In the seventeen years following the birth of Elizabeth, William became a father to seven more children. James in 1799, Johanna in 1803, Ann in 1805, Josepha in 1807, Susanna in 1808, Samuel in 1811 and finally Joseph in 1814. William had three strong sons to help him on the farm so it would be unlikely, except possibly at harvest time, that he needed to employ any full time labourers and what William grew on his farm was dependent on what type of soil he had. Cornish soil ranged from a sand/silt mix, to heavy clay, either was a challenge for any farmer as he trudged behind a horse drawn plough from dawn to dusk. Cornwall's climate was not such a demanding task master, a longer growing season and fewer sharp frosts made life a little bit easier for William than it would his contemporaries way up north. William may have grown some sort of cereal, by the time he had taken over Lescliston the turnip was becoming a popular crop in England, but because it reduced the lime in the soil, the Cornish farmer grew less of it. He may have kept a few sheep and a couple of cows. Life for Peggy along with their four daughters was busy too, in the spring and summer they would have grown herbs such as mint, lavender, rosemary and parsley and used them not only as flavouring for food but in medicinal remedies. The farm at Trevemper had a kitchen garden and an orchard where the women could grow vegetables such as beans and peas. In the late summer and autumn, Peggy and her children would have harvested, dried and stored their fruits and vegetables for winter meals, maybe making soap with leftover fats, adding lavender as scent.

Farmers like William, whose yearly tilling of the soil and wives like Peggy, dressed no doubt in the archetypal white bonnet, dark dress and white apron, scattering seeds onto the newly ploughed land helped Cornwall continue to prosper from its agricultural output. Landowners like Christopher Hawkins were using their profits, earned through the hard work of men like William, to refurbish their grand houses. The Carews at Antony had completely demolished their old home and replace it with a mansion, and John Nash, architect under the patronage of the Prince Regent, had converted the manor house at Caerhayes into a turreted stronghold. Towns were being transformed too, in Penzance there was a new Market House, Falmouth a new Custom House and brand new town houses were springing up, such as those that can still be seen on Lemon Street in Truro today.

By 1824, all of William’s children, apart from Elizabeth, were living and working on their father's farm and like others who grew up on farms, they would have spent their adolescence working with little or no pay. In later life, as a result of this, many children took farm tenancies, they would have known little else, the Mitchell children were no different. Elizabeth had married in 1821, and was now living in St Agnes, a small fishing village just a few miles down the coast. She presented William with four grandchildren before the marriage of her sister Ann in 1833. Family life was changing for William, he was growing older, he was sixty-six but in good health, Peggy it seems was not, by the August of 1833 she was dead, her body buried in Crantock Churchyard. Widowed William may have been, but he had a house full of grown up, unmarried children and a ninety acre farm to keep him busy.

Forty-three years on from the first set of land tax records, William was still living at the farmhouse at Lescliston and farming the same acreage, but interestingly the document also tells us about land in reference to its owners. The farmhouse and part of the land at Lescliston farmed by William, that was originally owned by Richard John's was now owned by one Edward Trevenen, the rest by Henry Hawkins, nephew of Sir Christopher. Edward Trevenen was possibly the son of John Trevenen of the Camborne/Helston family, an up and coming family with new money, whose patriarch had been a steward to the St Aubyn family of Clowance. As one family downsized another expanded but it seems that this made little difference to William’s holdings.

Seasons had come and gone, as had the years, and the arrival of 1857 the Cornish people watching the construction of Isambard Kingdom Brunel's Royal Albert Bridge over the Tamar at Saltash that had begun in 1854. The country as a whole saw a general election secured by Lord Palmerston's Whig party and Queen Victoria awarded the first Victoria Cross to sixty-six men for their actions during the Crimean War, but for William, 1857 would be his last.

In the decade that William had reached his eightieth year, only his two sons and a daughter were still living with him on the farm at Lescliston. William’s youngest daughter Susanna had left the home ten years previous and his younger son Joseph had died in 1842, this left James, Samuel and Josepha, but by the end of 1851 Josepha was dead too. Probably frail to look at but no doubt hardy, I can imagine William still being in control or at least trying to control work done on the farm. So, what was William Mitchell like? Was he the archetypal cheery, white shirted, black waist-coated, pitch-folk leaning, hay chewing farmer? No, of course not! Including the my earlier portrayal of Peggy, this view of a farmer is an ideal, an image in the Victorian paintings of Millais and later artists such as Charles James Adams or William Affleck. There is no doubt that William's life was hard in many ways, farming was back breaking work, but you could say that he may have had a life style that was closer to his landlord, than that of the often out of work labourer he later employed.

William as a tenant farmer, was at the centre of rural society and therefore we must assume he had a decent life of sorts, living to

the great age of ninety is testament to that. William must have had some advantages, healthy constitution was one, enough children, grandchildren and employed labourers to work the farm, and in a time when landowners such as Hawkins and Trevenen were viewed as symbols of authority, often feared by the tenant/farming community, we can assume that William possessed intelligence and a personally that kept him on the right side of his three landlords. Eventually though, time caught up with William Mitchell, he died, at his home of Lescliston in the October and was buried within the churchyard of Crantock Parish Church where his wife had lain for the past twenty years.

the great age of ninety is testament to that. William must have had some advantages, healthy constitution was one, enough children, grandchildren and employed labourers to work the farm, and in a time when landowners such as Hawkins and Trevenen were viewed as symbols of authority, often feared by the tenant/farming community, we can assume that William possessed intelligence and a personally that kept him on the right side of his three landlords. Eventually though, time caught up with William Mitchell, he died, at his home of Lescliston in the October and was buried within the churchyard of Crantock Parish Church where his wife had lain for the past twenty years.

On William's death his elder son James took on the tenancy at the Lescliston farm, the Trevemper lands had been farmed by Samuel since his marriage in 1852.