|

Business in Burgundy and Three

Important Battles |

Thomas Vaughan is thought not to have been part of Edward’s forces at St Albans, apart from joining the Yorkist forces at Ludlow, it seems that he took no real part in any major battles. Following his marriage, he and maybe Eleanor resided in his London property. As well as his official duties, which included overseeing the King’s Ordnance, living in the capital meant that he could concentrate on pursuing his claim to the Browne estates, it also meant that Vaughan was in a perfect position to witness the city's reaction to Warwick defeat.

Frightened at the thought that the city would succumb to looting and pillaging, wealthy merchants panicked and removed many of their personal valuables to a safer place. Whether Vaughan did this with his own belongings we do not know, but it has been suggested that he was involved with the removal of Henry’s treasury (also written as ‘Yorkist treasure’) to Ireland. The reasoning behind this action is not clear, it was probably taken on the order and on behalf of the king, but Vaughan’s reputation becomes a little tainted if we believe that he left the country with England’s treasury accompanied by a number of London’s (self-serving) aldermen only to be captured by the French, and released on payment of a ransom by the king himself.

Frightened at the thought that the city would succumb to looting and pillaging, wealthy merchants panicked and removed many of their personal valuables to a safer place. Whether Vaughan did this with his own belongings we do not know, but it has been suggested that he was involved with the removal of Henry’s treasury (also written as ‘Yorkist treasure’) to Ireland. The reasoning behind this action is not clear, it was probably taken on the order and on behalf of the king, but Vaughan’s reputation becomes a little tainted if we believe that he left the country with England’s treasury accompanied by a number of London’s (self-serving) aldermen only to be captured by the French, and released on payment of a ransom by the king himself.

This tale, like so many linked to Vaughan, history has embellished, but it is based on fact. The two aldermen who are stated as travelling with Vaughan were Philip Malpas and William Hatteclyffe.

Malpas was a Member of Parliament for London and a wealthy draper who had been convicted of unethical practices involving loans. He had been associated with Thomas Cook, a fellow draper and Lord Mayor of London since the Cade rebellion of 1450. Cook had negotiated with Cade on the city's behalf at Blackheath, the result of which had caused some unpleasantness between to two of them that was never really resolved and spilled over into the events in London of February 1461. Hatteclyffe, was physician to both Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou, he was asked to attend the king during his illness in 1454, and like Malpas (and Cook) was a Lancastrian deserter who profited from swapping their allegiances. The news of Margaret of Anjou and her victorious army heading for London was enough to put the fear of God into Malpas and Hatteclyffe, both fled the country along with Vaughan, eventually as just stated, captured by the French but later released. Thomas Vaughan being held by the French is a completely separate incident that occurred some sixteen years later in 1477, which involved Thomas Vaughan and is often linked to this affair and also adds to the confusion. This Thomas Vaughan was the illegitimate son of Roger Vaughan of Tretower (half-brother to Roger’s legitimate son Thomas Vaughan) Vaughan was held as a prisoner in France for a number of years eventually his release was secured when Edward IV paid £40 towards his ransom.

All three men did return to England, but if Malpas and Hattecliffe were with Vaughan, what happened to the treasury? If it was lost to England and taken to France to fill that nation’s coffers wouldn’t we have heard about it? After all, King John lost his treasure in The Wash over two hundred years before and we are still blaming him for it today. No, the answer is quite simple, these similar, but completely separate incidents have been merged into one that leads us to believe that Thomas Vaughan, Philip Malpas and William Hattecliffe were all in the same place at the same time. Malpas and Hattecliffe did flee the country, but not with ‘our’ Thomas Vaughan.

Malpas died in 1469 and Hattecliffe went on to become one of Edward’s physicians and Thomas Vaughan was trusted enough to secure the king’s treasury on behalf of the new regime taking it out of London and England to a safer place until Edward had secured the country. Edward would later intrust Vaughan with his and England’s other more important treasure, his firstborn son.

As we have learned, in the early months of 1461, Edward IV captured the hearts of the people of London, but the city wasn’t England and to win the counties hearts he would have to defeat the Lancastrians once and for all, and at Towton Edward would show no mercy.

Malpas was a Member of Parliament for London and a wealthy draper who had been convicted of unethical practices involving loans. He had been associated with Thomas Cook, a fellow draper and Lord Mayor of London since the Cade rebellion of 1450. Cook had negotiated with Cade on the city's behalf at Blackheath, the result of which had caused some unpleasantness between to two of them that was never really resolved and spilled over into the events in London of February 1461. Hatteclyffe, was physician to both Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou, he was asked to attend the king during his illness in 1454, and like Malpas (and Cook) was a Lancastrian deserter who profited from swapping their allegiances. The news of Margaret of Anjou and her victorious army heading for London was enough to put the fear of God into Malpas and Hatteclyffe, both fled the country along with Vaughan, eventually as just stated, captured by the French but later released. Thomas Vaughan being held by the French is a completely separate incident that occurred some sixteen years later in 1477, which involved Thomas Vaughan and is often linked to this affair and also adds to the confusion. This Thomas Vaughan was the illegitimate son of Roger Vaughan of Tretower (half-brother to Roger’s legitimate son Thomas Vaughan) Vaughan was held as a prisoner in France for a number of years eventually his release was secured when Edward IV paid £40 towards his ransom.

All three men did return to England, but if Malpas and Hattecliffe were with Vaughan, what happened to the treasury? If it was lost to England and taken to France to fill that nation’s coffers wouldn’t we have heard about it? After all, King John lost his treasure in The Wash over two hundred years before and we are still blaming him for it today. No, the answer is quite simple, these similar, but completely separate incidents have been merged into one that leads us to believe that Thomas Vaughan, Philip Malpas and William Hattecliffe were all in the same place at the same time. Malpas and Hattecliffe did flee the country, but not with ‘our’ Thomas Vaughan.

Malpas died in 1469 and Hattecliffe went on to become one of Edward’s physicians and Thomas Vaughan was trusted enough to secure the king’s treasury on behalf of the new regime taking it out of London and England to a safer place until Edward had secured the country. Edward would later intrust Vaughan with his and England’s other more important treasure, his firstborn son.

As we have learned, in the early months of 1461, Edward IV captured the hearts of the people of London, but the city wasn’t England and to win the counties hearts he would have to defeat the Lancastrians once and for all, and at Towton Edward would show no mercy.

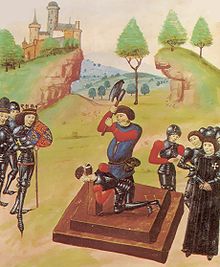

While Thomas Vaughan was out of the country, Edward had left London and reached the Yorkshire town of Pontefract fourteen days later. At this point in time, the main Lancastrian army was probably at York meaning that the sides were separated by two rivers, the Wharf in the north and more importantly, the Aire in the south. The crossing on the river Aire at Ferrybridge was to play host to an event that would eventually lead to the more famous Battle of Towton two days later. By the time dusk had arrived on the 27th, Richard Earl of Warwick had reached Ferrybridge and found the Lancastrian forces on the Aire's other bank had made a good job of destroying the bridge, this had the effect of cutting off Warwick’s vanguard. A small Yorkist force had left while Warwick’s men had made another ‘bridge’ out of planks of wood. Edward himself was still south of the river and had recently received word of the arrival of a large number of Lancastrian soldiers under the command of the Duke of Somerset who had set up camp between the villages of Towton and Saxton. The morning of the 28th of March saw Warwick’s army taken by surprise by Lancastrian soldiers and in the confusion and panic many of Warwick's troops lost their lives, and it was at this point, that Richard Neville had been hit in the leg by an archers arrow. Edward Hall, the fifteenth-century chronicler, does write of Warwick’s leg wound but has him heroically riding to inform the king of the battle and then has him nobly cutting the throat of his horse to prove his commitment to the cause. It is unlikely that Warwick did such a thing, but it does show how committed men were to the cause.

Professor Charles Ross, who wrote a biography of Edward IV, suggests that fifty thousand men took part at Towton, others state it was in the region of thirty five thousand. However, on the smokey, body-strewn, blood-soaked battlefield of Towton, that cold day of the 29th March 1461, it is said that 28,000 men lay dead or dying. Edward, the nineteen-year-old, six foot four adonis, had been victorious, not only that he had broken the Lancastrian spirit.

Following the battle, Henry VI, his queen, and their son fled the scene accompanied by Henry Beaufort and Henry Holland. Before the coronation, scheduled for the 28th June, Edward purposefully made his way to York to remove the heads of both his father and brother from Micklegate Bar and replace them with the head of Thomas Courtenay, the Earl of Devon, a fitting end for one who was well known for his love of brutality on the battlefield. Beaufort would go on to lose his life at Hexham in the May of 1464. In the Lancastrian's last ditched attempt at resistance, Henry VI was captured yet again, and the feisty Margaret of Anjou and her son found themselves exiled in France still convinced that this was not the end.

An administrator and not a fighter, Thomas Vaughan spent much of his time during the reign of Edward IV as an ambassador. In the October of 1462 he was engaged, along with John Wenlock, the Chief Butler of England and “fence sitter par excellence” in arranging a commercial treaty with Burgundy. In the summer of 1465 Vaughan was appointed the dual role of Treasurer of the King's Chamber and Master of the Jewel Office. This placement shows Vaughan’s importance within the royal court, a man on which Edward could rely. The office of the Treasurer of the Chamber meant that he had dealings with the king on a personal and day-to-day basis, he was accountable for the chamber accounts to the king alone and not to the exchequer. Records show that Vaughan was still in this position in the May of 1482 but not by the February of the following year. His position as Master of the Jewel Office he held until 1483, possibly until his death. Vaughan was responsible for the gold and silver plate that was used at Edward’s table, also Edward’s jewelry, that is, chains and loose jewelry that was not fixed to the king’s clothing.

Before Vaughan was sent on his next diplomatic expedition to Burgundy, a crisis was looming in the royal court that in its infancy would unsettle, but eventually bring down everything Edward had worked so hard to achieve.

For a number of years, depending on who was on the throne at the time, England had been on good terms with either France or Burgundy, using this to his advantage Warwick proposed to the September council that a peace treaty be signed with Louis XI of France. Also, some members of the council had agreed with Warwick’s suggestion that it was high time Edward was married. Louis thought so too, an English alliance with France was far better for him than a Burgundian alliance, eventually, Warwick succumbed to a bit of flattery and bribery and put it to Edward that Bona of Savoy would be a perfect match. To the surprise of many, Edward indicated that the idea of marriage was indeed a good one, he never batted an eyelid at the suggestion of a French bride, even though he himself favoured Burgundy. After a long silence, he finally relayed the fact that he had already made his choice and in fact, he had already married one Elizabeth Grey, a member of the lowly Woodville family of Northamptonshire.

Edward, as Paul Murray Kendall quite rightly points out, had succumbed to lust and not with a weak, mild-mannered virgin either, but with a strong-willed widow with two young sons, a widowed mother and eight siblings to boot. Edward had undertaken all this without the knowledge of one man who was so instrumental in bringing him to the throne, Richard ‘the Kingmaker’ Neville.

Edward’s news was shattering, Warwick had pledged Edward, as near as ‘damn it’, in marriage to the sister of the queen of France. Edwards's irresponsible behaviour humiliated Warwick and ruined his plans, his prestige both at home and abroad was in tatters, and to say that Warwick was enraged would be an understatement, the dagger of betrayal had cut too deep and it was a wound that would never heal. Richard Neville could do nothing but reluctantly accept the situation. Even though Edward made some moves towards appeasement raising Neville’s brother George from his position as Chancellor to the Archbishop of York, their friendship never recovered. It would prove too much for Warwick making it impossible for him to stand back and watch as noble titles, as well as advantageous marriages, headed the way of all the queen's relatives. England’s elite lost the opportunity of taking a step up the social ladder, but Richard Neville lost what was really important to him, the ear of the king. If Warwick couldn’t get the power he wanted through Edward there was always another brother. During the years that followed Warwick contemplated rebellion, he was also preparing the bait to tempt George, Duke of Clarence into his web, and in the meantime, Edward had fathered two daughters, the arrival of an heir would not come for another three years.

In the summer of 1467, the year of Edward's daughter Mary’s birth, Vaughan had been tasked with making arrangements for the marriage of the king’s sister Margaret of York. Earlier that year, Charles the Bold became Duke of Burgundy on the death of his father, this followed the death of Charles's second wife Isabel of Bourbon who had died in 1465.

Nine years earlier, Charles's mother, Isabella of Burgundy, the granddaughter of John of Gaunt, had favoured a match with England when considering a second wife for her son, but marriage into the present English royal family was out of the question due to the reigning monarch's consort Margaret of Anjou, being the niece of Charles VII of France who was Burgundy’s bitterest enemy, it was then that Charles married Isabel. Eleven years later, in 1465 after the death of Isabel, Charles was in need of a new wife. This time, however, the Yorkists were in a far better position than they had been in 1454, now Edward IV was king of England. Edward's sister Margaret, the youngest daughter of Richard, Duke of York and Cecily Neville was the chosen bride. Thomas Vaughan, along with others headed for Burgundy to meet with Burgundian ambassador Philippe Pot. Pot had been involved in all major political matters of his time and proved himself to be a skilled diplomat and negotiator, he had been an ambassador in London and had secured the release of Charles of Orleans who had been taken prisoner at Agincourt and had been an English prisoner for twenty-five years. Pot was also employed by Charles the Bold in obtaining a marriage contract with Catherine, daughter of Charles VII of France and on her death used once again in 1450 to secure the hand of Isabella of Bourbon. By 1468 marriage negotiations had been successful, and the contract was completed by the end of February 1468 and signed by Edward IV the March.

Thomas Vaughan accompanied the duchess on her journey to Burgundy, the party left Margate on the 23rd June 1468 and arrived in Amsterdam on the 25th. Arrangements had been made for Margaret to meet Charles on the 27th and the couple were married in a private ceremony on the 3rd of July at the home of a wealthy merchant and this was followed by an extravagant wedding feast, the like Vaughan had probably never seen before. In an account of the feast given by Olivier de la Marche, a courtier, soldier and chronicler and friend of Charles, Marche states that Vaughan was among the English nobles, along with Lord Scales and John Woodville, brother to Edward’s queen, John Howard, Lord Dacre and William Parr, all who followed the litter of the new bride to the festivities. These men received gifts from Charles in the form of rather large amounts of money for their efforts in promoting his marriage with Margaret of York, Vaughan received payment to the value of £375, which is the equivalent today of over £187,000, John Woodville received, in today's money, just over £315,000. By the end of the year Thomas Vaughan (history mixes up the two Vaughan’s again at this point) was commissioned by Charles the Bold to introduce Edward to the orders statutes before inducting him into the Order of the Golden Fleece. Vaughan was again in Burgundy in the summer of 1470 to invest Charles the Bold into the Order of the Garter, as we can see the relationship between England and Burgundy was cordial, this would prove advantageous seeing as the wounded and deeply vengeful Earl of Warwick had succeeded in returning Henry VI to the throne of England.

As we have learned the turning point for Richard Neville was Edward's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, but it was not the only thing that initiated Warwick's turning from the Yorkists, other factors were Woodville men in important administrative roles, the king’s refusal to sanction the marriage of Warwick’s daughter to George, Duke of Clarence, the influence of Herbert family and of course the rise of ‘the new man’ such as Sir John Fogge, whose placement into prominent positions may have rubbed salt into Warwick’s wounds.

Lastly, Richard Neville didn’t like not getting what he wanted, one thing he really wanted was a Dukedom.

It is probable that Vaughan was still going about his duties in Burgundy at this time and it is unlikely that he made it back to England before Edward was forced to flee the country leaving from the Norfolk port of King's Lynn at the end of September 1470, Thomas Vaughan would have been one friendly face on his arrival. It has been estimated that up to 900 men travelled with Edward, one of these men was William Hastings. He, like Vaughan, had been sent abroad on a number of diplomatic assignments, and along with the King and more than likely Vaughan, were entertained during their exile by Louis of Gruthuyse. Gruthuyse was a Flemish nobleman, he was a councillor to Charles the Bold who had helped Edward in his hour of need, supplying him with food, clothes and money. Later, Edward would return the favour, lavishing gifts and the title of Earl of Winchester on him.

Although Edward had brought the Lancastrians to their knees at Towton, he was still concerned with Lancastrian plots, surprisingly he was blind to the fact that Warwick was cunning, and we can be fairly sure that Warwick was clever enough not to be seen to be involved in plotting the downfall of the House of York. However, Thomas Vaughan never swayed in his loyalty to Edward, but in the present climate, a number of other people were implicated. John Wenlock and Thomas Cook, like Scott, Fogge and Horne were acquaintances of Vaughan’s from around 1450, were arrested on suspicion of treason. Wenlock’s servant had named them under torture, but both were released on a fine, (Cook was fined over £5000 pounds,) and others were executed on Tower Hill. The Earl of Warwick's name was never officially mentioned, however, following a standoff in a field in the village of Empringham (Battle of Losecote Field,) which involved Sir Robert Welles, it is plain to see that Warwick was the puppeteer. Letters, incriminating Warwick, were found in a chest that was recovered among the belongings of Sir Robert Welles goes someway back up this fact. Following Welles arrest and in his confession he writes

“ I have welle understand my many meagges, as welle from my Lord of Warwicke, and they entended to make grete risinges, as forthorthy as ever I couth understand , to th’entent to make the duc of Clarence king…..Also, I say that had beene the said duc and erls provokings that we at this tyme would no durst have made eny commocion or sturing, but upon there comforts we did what we did”......Also, I say that I and my dadier had often times letters of credence from my said lordes”

It is not hard to imagine what the state of the country was in, anarchy would possibly be a good word to describe it. While most were troubled, the triumphant Richard Neville was in his element as he placed the crown of England, once again, on the head of Henry VI. Released from the Tower of London, the poor man’s physical health was weak and his mental health was clearly unstable. As these two men stood together it was obvious to everybody who was in charge. Real power was now in the gauntleted hand of Richard, Earl of Warwick, the King’s Lieutenant of the Realm.

All were wondering what would happen next.

The six months, a period of time that has come to be known as the Readeption of Henry VI, Thomas Vaughan disappears from the radar as far as official records are concerned, so it is difficult to say with accuracy exactly what Vaughan was doing, it appears he played no ‘physical’ part in the two battles that took place within between 14th April and the 4th May 1471.

At the beginning of Henry’s new reign, only the important offices within the government were filled, most of them with men loyal to Warwick, so it likely that Vaughan still had the authority of his post as Master of the King’s Ordnance. George Neville returned as Chancellor and John Neville were given back his former post. John Talbot, the Earl of Shrewsbury and John de Vere, the Earl of Oxford returned to their estates as did Thomas Courtenay, Earl of Devon. Jasper Tudor arrived in the city to discuss the Earldom of Richmond but was told that Clarence had been rewarded with that title for services rendered.

With Vaughan in the background for now and the House of Lancaster back in power, Vaughan's one-time housemate, Jasper Tudor was negotiating the wardship of his nephew, Henry. The pair had arrived in London, and Tudor was reunited with his devoted mother, Margaret Beaufort, but the end of November, both Jasper and Henry had returned to Wales empty-handed.

As the Tudor uncle and nephew made their way west, the November parliament met, attainders against Lancastrian nobles were lifted and new ones placed on Edward and his brother Richard, but more importantly for Neville, if not for the country, a treaty of peace was signed with the French. This, of course, alienated the Burgundians, but it did serve as a kick up the backside for Charles the Bold and Edward, and Louis was champing at the bit for France and England to get stuck into Burgundy. If Warwick hoped that Margaret and her son would return home to England to play their part, he would have to wait a while. Henry’s queen had no intention of returning, she still did not trust Warwick and despite the fact that Charles the Bold was Edward’s brother-in-law, it seem that he had no intention of helping him out either. With war with France, imminent Charles soon changed his mind. Edward, with the encouragement of Louis of Gruthuyse and no doubt realising that this was his big chance to regain his throne, began talks with Charles the Bold. In the second week of March, Warwick had received news that ships flying the Yorkist banner had been spotted off the coast of Norfolk, and by the 14th of March, Edward, Hasting and Richard, Duke of Gloucester had arrived at Ravenspur on the east coast of England, the very port Henry IV had landed seventy years before to claim the English throne.

As previously stated there is no mention of Thomas Vaughan’s actions at this time, it may be that he had crossed the English Channel with Edward and made his way to the city in the hope of making available arms from the Tower. When Edward arrived on the 11th of April, he entered London unopposed, supplied his troops with arms and left again heading north. He arrived at Monken Hadley on the 13th of April 1471. The Yorkist forces made their camp next to the village church on a hill that overlooked the town Barnet, that night he placed his troops in their battle positions, and the following morning he would find that they were very close to Warwick’s lines.

Edward's force at Barnet, according to the unknown writer of The Arrivall, numbered nine thousand, but it is thought there were far more than this, Edward himself landed with about two thousand, six thousand men joined his army at Nottingham, three thousand at Leicester, the Duke of Clarence, who had now switched his allegiance again, brought around seven thousand, but Warwick commanded many more.

Easter morning dawned grey and foggy, Edward instructed that no fires be lit and no noise be made so as not to give their position away but eventually the noise of the clash of sword on sword could be heard.

The Battle of Barnet had begun and it ended with it the death of Richard Neville.

Charles Oman in his book “Warwick” writes:

“He (Warwick) began to draw back towards the line of thickets and hedges which had lairn behind his army. But there the fate met him that had befallen so many of his enemies, at St Albans, and Northampton, at Towton and Hexham. His heavy armour made rapid flight impossible; and in the edge of Wrotham Wood he was surrounded by the pursuing enemy, wounded, beaten down and slain.”

Professor Charles Ross, who wrote a biography of Edward IV, suggests that fifty thousand men took part at Towton, others state it was in the region of thirty five thousand. However, on the smokey, body-strewn, blood-soaked battlefield of Towton, that cold day of the 29th March 1461, it is said that 28,000 men lay dead or dying. Edward, the nineteen-year-old, six foot four adonis, had been victorious, not only that he had broken the Lancastrian spirit.

Following the battle, Henry VI, his queen, and their son fled the scene accompanied by Henry Beaufort and Henry Holland. Before the coronation, scheduled for the 28th June, Edward purposefully made his way to York to remove the heads of both his father and brother from Micklegate Bar and replace them with the head of Thomas Courtenay, the Earl of Devon, a fitting end for one who was well known for his love of brutality on the battlefield. Beaufort would go on to lose his life at Hexham in the May of 1464. In the Lancastrian's last ditched attempt at resistance, Henry VI was captured yet again, and the feisty Margaret of Anjou and her son found themselves exiled in France still convinced that this was not the end.

An administrator and not a fighter, Thomas Vaughan spent much of his time during the reign of Edward IV as an ambassador. In the October of 1462 he was engaged, along with John Wenlock, the Chief Butler of England and “fence sitter par excellence” in arranging a commercial treaty with Burgundy. In the summer of 1465 Vaughan was appointed the dual role of Treasurer of the King's Chamber and Master of the Jewel Office. This placement shows Vaughan’s importance within the royal court, a man on which Edward could rely. The office of the Treasurer of the Chamber meant that he had dealings with the king on a personal and day-to-day basis, he was accountable for the chamber accounts to the king alone and not to the exchequer. Records show that Vaughan was still in this position in the May of 1482 but not by the February of the following year. His position as Master of the Jewel Office he held until 1483, possibly until his death. Vaughan was responsible for the gold and silver plate that was used at Edward’s table, also Edward’s jewelry, that is, chains and loose jewelry that was not fixed to the king’s clothing.

Before Vaughan was sent on his next diplomatic expedition to Burgundy, a crisis was looming in the royal court that in its infancy would unsettle, but eventually bring down everything Edward had worked so hard to achieve.

For a number of years, depending on who was on the throne at the time, England had been on good terms with either France or Burgundy, using this to his advantage Warwick proposed to the September council that a peace treaty be signed with Louis XI of France. Also, some members of the council had agreed with Warwick’s suggestion that it was high time Edward was married. Louis thought so too, an English alliance with France was far better for him than a Burgundian alliance, eventually, Warwick succumbed to a bit of flattery and bribery and put it to Edward that Bona of Savoy would be a perfect match. To the surprise of many, Edward indicated that the idea of marriage was indeed a good one, he never batted an eyelid at the suggestion of a French bride, even though he himself favoured Burgundy. After a long silence, he finally relayed the fact that he had already made his choice and in fact, he had already married one Elizabeth Grey, a member of the lowly Woodville family of Northamptonshire.

Edward, as Paul Murray Kendall quite rightly points out, had succumbed to lust and not with a weak, mild-mannered virgin either, but with a strong-willed widow with two young sons, a widowed mother and eight siblings to boot. Edward had undertaken all this without the knowledge of one man who was so instrumental in bringing him to the throne, Richard ‘the Kingmaker’ Neville.

Edward’s news was shattering, Warwick had pledged Edward, as near as ‘damn it’, in marriage to the sister of the queen of France. Edwards's irresponsible behaviour humiliated Warwick and ruined his plans, his prestige both at home and abroad was in tatters, and to say that Warwick was enraged would be an understatement, the dagger of betrayal had cut too deep and it was a wound that would never heal. Richard Neville could do nothing but reluctantly accept the situation. Even though Edward made some moves towards appeasement raising Neville’s brother George from his position as Chancellor to the Archbishop of York, their friendship never recovered. It would prove too much for Warwick making it impossible for him to stand back and watch as noble titles, as well as advantageous marriages, headed the way of all the queen's relatives. England’s elite lost the opportunity of taking a step up the social ladder, but Richard Neville lost what was really important to him, the ear of the king. If Warwick couldn’t get the power he wanted through Edward there was always another brother. During the years that followed Warwick contemplated rebellion, he was also preparing the bait to tempt George, Duke of Clarence into his web, and in the meantime, Edward had fathered two daughters, the arrival of an heir would not come for another three years.

In the summer of 1467, the year of Edward's daughter Mary’s birth, Vaughan had been tasked with making arrangements for the marriage of the king’s sister Margaret of York. Earlier that year, Charles the Bold became Duke of Burgundy on the death of his father, this followed the death of Charles's second wife Isabel of Bourbon who had died in 1465.

Nine years earlier, Charles's mother, Isabella of Burgundy, the granddaughter of John of Gaunt, had favoured a match with England when considering a second wife for her son, but marriage into the present English royal family was out of the question due to the reigning monarch's consort Margaret of Anjou, being the niece of Charles VII of France who was Burgundy’s bitterest enemy, it was then that Charles married Isabel. Eleven years later, in 1465 after the death of Isabel, Charles was in need of a new wife. This time, however, the Yorkists were in a far better position than they had been in 1454, now Edward IV was king of England. Edward's sister Margaret, the youngest daughter of Richard, Duke of York and Cecily Neville was the chosen bride. Thomas Vaughan, along with others headed for Burgundy to meet with Burgundian ambassador Philippe Pot. Pot had been involved in all major political matters of his time and proved himself to be a skilled diplomat and negotiator, he had been an ambassador in London and had secured the release of Charles of Orleans who had been taken prisoner at Agincourt and had been an English prisoner for twenty-five years. Pot was also employed by Charles the Bold in obtaining a marriage contract with Catherine, daughter of Charles VII of France and on her death used once again in 1450 to secure the hand of Isabella of Bourbon. By 1468 marriage negotiations had been successful, and the contract was completed by the end of February 1468 and signed by Edward IV the March.

Thomas Vaughan accompanied the duchess on her journey to Burgundy, the party left Margate on the 23rd June 1468 and arrived in Amsterdam on the 25th. Arrangements had been made for Margaret to meet Charles on the 27th and the couple were married in a private ceremony on the 3rd of July at the home of a wealthy merchant and this was followed by an extravagant wedding feast, the like Vaughan had probably never seen before. In an account of the feast given by Olivier de la Marche, a courtier, soldier and chronicler and friend of Charles, Marche states that Vaughan was among the English nobles, along with Lord Scales and John Woodville, brother to Edward’s queen, John Howard, Lord Dacre and William Parr, all who followed the litter of the new bride to the festivities. These men received gifts from Charles in the form of rather large amounts of money for their efforts in promoting his marriage with Margaret of York, Vaughan received payment to the value of £375, which is the equivalent today of over £187,000, John Woodville received, in today's money, just over £315,000. By the end of the year Thomas Vaughan (history mixes up the two Vaughan’s again at this point) was commissioned by Charles the Bold to introduce Edward to the orders statutes before inducting him into the Order of the Golden Fleece. Vaughan was again in Burgundy in the summer of 1470 to invest Charles the Bold into the Order of the Garter, as we can see the relationship between England and Burgundy was cordial, this would prove advantageous seeing as the wounded and deeply vengeful Earl of Warwick had succeeded in returning Henry VI to the throne of England.

As we have learned the turning point for Richard Neville was Edward's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, but it was not the only thing that initiated Warwick's turning from the Yorkists, other factors were Woodville men in important administrative roles, the king’s refusal to sanction the marriage of Warwick’s daughter to George, Duke of Clarence, the influence of Herbert family and of course the rise of ‘the new man’ such as Sir John Fogge, whose placement into prominent positions may have rubbed salt into Warwick’s wounds.

Lastly, Richard Neville didn’t like not getting what he wanted, one thing he really wanted was a Dukedom.

It is probable that Vaughan was still going about his duties in Burgundy at this time and it is unlikely that he made it back to England before Edward was forced to flee the country leaving from the Norfolk port of King's Lynn at the end of September 1470, Thomas Vaughan would have been one friendly face on his arrival. It has been estimated that up to 900 men travelled with Edward, one of these men was William Hastings. He, like Vaughan, had been sent abroad on a number of diplomatic assignments, and along with the King and more than likely Vaughan, were entertained during their exile by Louis of Gruthuyse. Gruthuyse was a Flemish nobleman, he was a councillor to Charles the Bold who had helped Edward in his hour of need, supplying him with food, clothes and money. Later, Edward would return the favour, lavishing gifts and the title of Earl of Winchester on him.

Although Edward had brought the Lancastrians to their knees at Towton, he was still concerned with Lancastrian plots, surprisingly he was blind to the fact that Warwick was cunning, and we can be fairly sure that Warwick was clever enough not to be seen to be involved in plotting the downfall of the House of York. However, Thomas Vaughan never swayed in his loyalty to Edward, but in the present climate, a number of other people were implicated. John Wenlock and Thomas Cook, like Scott, Fogge and Horne were acquaintances of Vaughan’s from around 1450, were arrested on suspicion of treason. Wenlock’s servant had named them under torture, but both were released on a fine, (Cook was fined over £5000 pounds,) and others were executed on Tower Hill. The Earl of Warwick's name was never officially mentioned, however, following a standoff in a field in the village of Empringham (Battle of Losecote Field,) which involved Sir Robert Welles, it is plain to see that Warwick was the puppeteer. Letters, incriminating Warwick, were found in a chest that was recovered among the belongings of Sir Robert Welles goes someway back up this fact. Following Welles arrest and in his confession he writes

“ I have welle understand my many meagges, as welle from my Lord of Warwicke, and they entended to make grete risinges, as forthorthy as ever I couth understand , to th’entent to make the duc of Clarence king…..Also, I say that had beene the said duc and erls provokings that we at this tyme would no durst have made eny commocion or sturing, but upon there comforts we did what we did”......Also, I say that I and my dadier had often times letters of credence from my said lordes”

It is not hard to imagine what the state of the country was in, anarchy would possibly be a good word to describe it. While most were troubled, the triumphant Richard Neville was in his element as he placed the crown of England, once again, on the head of Henry VI. Released from the Tower of London, the poor man’s physical health was weak and his mental health was clearly unstable. As these two men stood together it was obvious to everybody who was in charge. Real power was now in the gauntleted hand of Richard, Earl of Warwick, the King’s Lieutenant of the Realm.

All were wondering what would happen next.

The six months, a period of time that has come to be known as the Readeption of Henry VI, Thomas Vaughan disappears from the radar as far as official records are concerned, so it is difficult to say with accuracy exactly what Vaughan was doing, it appears he played no ‘physical’ part in the two battles that took place within between 14th April and the 4th May 1471.

At the beginning of Henry’s new reign, only the important offices within the government were filled, most of them with men loyal to Warwick, so it likely that Vaughan still had the authority of his post as Master of the King’s Ordnance. George Neville returned as Chancellor and John Neville were given back his former post. John Talbot, the Earl of Shrewsbury and John de Vere, the Earl of Oxford returned to their estates as did Thomas Courtenay, Earl of Devon. Jasper Tudor arrived in the city to discuss the Earldom of Richmond but was told that Clarence had been rewarded with that title for services rendered.

With Vaughan in the background for now and the House of Lancaster back in power, Vaughan's one-time housemate, Jasper Tudor was negotiating the wardship of his nephew, Henry. The pair had arrived in London, and Tudor was reunited with his devoted mother, Margaret Beaufort, but the end of November, both Jasper and Henry had returned to Wales empty-handed.

As the Tudor uncle and nephew made their way west, the November parliament met, attainders against Lancastrian nobles were lifted and new ones placed on Edward and his brother Richard, but more importantly for Neville, if not for the country, a treaty of peace was signed with the French. This, of course, alienated the Burgundians, but it did serve as a kick up the backside for Charles the Bold and Edward, and Louis was champing at the bit for France and England to get stuck into Burgundy. If Warwick hoped that Margaret and her son would return home to England to play their part, he would have to wait a while. Henry’s queen had no intention of returning, she still did not trust Warwick and despite the fact that Charles the Bold was Edward’s brother-in-law, it seem that he had no intention of helping him out either. With war with France, imminent Charles soon changed his mind. Edward, with the encouragement of Louis of Gruthuyse and no doubt realising that this was his big chance to regain his throne, began talks with Charles the Bold. In the second week of March, Warwick had received news that ships flying the Yorkist banner had been spotted off the coast of Norfolk, and by the 14th of March, Edward, Hasting and Richard, Duke of Gloucester had arrived at Ravenspur on the east coast of England, the very port Henry IV had landed seventy years before to claim the English throne.

As previously stated there is no mention of Thomas Vaughan’s actions at this time, it may be that he had crossed the English Channel with Edward and made his way to the city in the hope of making available arms from the Tower. When Edward arrived on the 11th of April, he entered London unopposed, supplied his troops with arms and left again heading north. He arrived at Monken Hadley on the 13th of April 1471. The Yorkist forces made their camp next to the village church on a hill that overlooked the town Barnet, that night he placed his troops in their battle positions, and the following morning he would find that they were very close to Warwick’s lines.

Edward's force at Barnet, according to the unknown writer of The Arrivall, numbered nine thousand, but it is thought there were far more than this, Edward himself landed with about two thousand, six thousand men joined his army at Nottingham, three thousand at Leicester, the Duke of Clarence, who had now switched his allegiance again, brought around seven thousand, but Warwick commanded many more.

Easter morning dawned grey and foggy, Edward instructed that no fires be lit and no noise be made so as not to give their position away but eventually the noise of the clash of sword on sword could be heard.

The Battle of Barnet had begun and it ended with it the death of Richard Neville.

Charles Oman in his book “Warwick” writes:

“He (Warwick) began to draw back towards the line of thickets and hedges which had lairn behind his army. But there the fate met him that had befallen so many of his enemies, at St Albans, and Northampton, at Towton and Hexham. His heavy armour made rapid flight impossible; and in the edge of Wrotham Wood he was surrounded by the pursuing enemy, wounded, beaten down and slain.”

There are a number of different versions regarding the death of Richard Neville. Philippe de Commines suggests that it was his brother's fault that Warwick died that day. Montagu had persuaded Warwick to dismount his horse and fight at ground level, he subsequently died at the hands of the Yorkist infantry. Another version says he was killed while fleeing.

Did Edward mourn his passing? Maybe! Richard, Duke of Gloucester certainly did.

With the plunge of a Yorkist sword Edward had dealt with Warwick, he also had eradicated a number of important Lancastrian nobles. However, the two most important members were still at large. Margaret of Anjou and her son had set foot in England the very same day its soil ran red with Warwick’s blood. Within three weeks, the Lancastrian forces under Edmund Beaufort had taken up arms, but they would once again be defeated.

The Battle of Tewkesbury saw Edward and Hasting at the rear, and Richard, Duke of Gloucester leading the vanguard. Sir John Wenlock's inactivity on the battlefield was the focal point for Gloucester's men who made their attack, but it was cause for concern for Somerset. Following a ‘mistake’ by Wenlock, many Lancastrian men lost their lives fleeing across a field called Bloody Meadow. Wenlock died that day, wearing his Lancastrian coat, allegedly slain by Beaufort for holding back his men. Somerset is said to have accused him of treason and killed him there and then. Among those who died that day was John Courtenay, it was his brother’s head that Edward had impaled on a spike in place of his father and brother’s after Towton in 1461. Edward Beaufort was executed two days later.

Did Edward mourn his passing? Maybe! Richard, Duke of Gloucester certainly did.

With the plunge of a Yorkist sword Edward had dealt with Warwick, he also had eradicated a number of important Lancastrian nobles. However, the two most important members were still at large. Margaret of Anjou and her son had set foot in England the very same day its soil ran red with Warwick’s blood. Within three weeks, the Lancastrian forces under Edmund Beaufort had taken up arms, but they would once again be defeated.

The Battle of Tewkesbury saw Edward and Hasting at the rear, and Richard, Duke of Gloucester leading the vanguard. Sir John Wenlock's inactivity on the battlefield was the focal point for Gloucester's men who made their attack, but it was cause for concern for Somerset. Following a ‘mistake’ by Wenlock, many Lancastrian men lost their lives fleeing across a field called Bloody Meadow. Wenlock died that day, wearing his Lancastrian coat, allegedly slain by Beaufort for holding back his men. Somerset is said to have accused him of treason and killed him there and then. Among those who died that day was John Courtenay, it was his brother’s head that Edward had impaled on a spike in place of his father and brother’s after Towton in 1461. Edward Beaufort was executed two days later.

The most notable death at Tewksbury was Edward, Prince of Wales, Henry VI’s son and heir. Shakespeare, as you might imagine, makes much of the manner of the boy’s death, having Edward, slapping the eighteen year old with his gauntleted hand before Gloucester and Clarence both stab him to death. What most probably happened was that the boy was found and beheaded, allegedly by the Duke of Clarence. What of Margaret of Anjou, the thorn in the side of the Yorkist? Following her capture, she spent a number of years of her captivity in the charge of Alice, Duchess of Suffolk, a kindred spirit, another woman who ruthlessly pursued the interest of her son.

Edward was once again in possession of the crown of England, the Lancastrians were defeated, there was a new royal heir, Clarence was onside once more, Richard had married Warwick's second daughter Anne and the vast Beauchamp/Neville inheritance was now part of his families estates. For Edward, this would be the last time he would deal with the Lancastrians, he was dead by the time they reappeared, but in the meantime, Jasper Tudor had whisked the teenage Henry Tudor over to Brittany, the Earl of Oxford who had beaten Hastings forces at Barnet was hiding among the Scots.

Between them, these three men would see the end of the mighty Plantagenet dynasty and replace it with the name of Tudor.

Edward was once again in possession of the crown of England, the Lancastrians were defeated, there was a new royal heir, Clarence was onside once more, Richard had married Warwick's second daughter Anne and the vast Beauchamp/Neville inheritance was now part of his families estates. For Edward, this would be the last time he would deal with the Lancastrians, he was dead by the time they reappeared, but in the meantime, Jasper Tudor had whisked the teenage Henry Tudor over to Brittany, the Earl of Oxford who had beaten Hastings forces at Barnet was hiding among the Scots.

Between them, these three men would see the end of the mighty Plantagenet dynasty and replace it with the name of Tudor.