|

Hendley

5th to 12th Century in the Manor of Coursehorn |

Kent, at the time of the early Hendley family was a breeding ground of revolt and anarchy, many of those who were exiled or fled the country left from Kentish ports, likewise, many a man who had a mind to conquer England entered via Kent, this county it seems, was the gateway into England. Travellers from southern Europe first set eyes on this county some twenty-three centuries ago and the Romans first view of England was the White Cliffs of Dover. In 1066, following the Battle of Hastings, the Normans, who were diverted on their journey to London by the quagmire that was the aforementioned Weald Forest, brutally harried their way through Kent. These Normans, once established in their new kingdom, needed to defend themselves, they did this by building castles. Kentish castles at Dover, Rochester and Canterbury were three of the largest and it wasn’t only the secular community who were building, those within the religious community were doing the same, they built churches, chapels and chantries, vast cathedrals were also built to the glory of God and two of the oldest are also in Kent - the aforementioned Rochester and Canterbury, the last being the site of the famous murder of its Archbishop Thomas Becket in 1170. Many of the townspeople who lived in the shadow of these mighty castles and magnificent cathedrals were the poor born of Germanic stock who scraped together a living in the shadow of those who controlled and governed. As time passed these lowly inhabitants became tradesmen, and later those who were more successful established a new sector of society - the merchant. As these merchants became rich they formed guilds, these guilds became powerful and controlled the way in which trade was conducted, and they applied their own rules too. This new elite class had wealth and status, and they wanted a fair system of taxation, the poor wanted the opportunity for a better life, both wanted justice. These men of Kent, despite which category they belonged, felt particularly put upon by government and crown alike, these men would voice their grievances, however the response to this by those in authority would cause riots and rebellion, bloodshed and death all across Kent.

However, before the castles and cathedrals were built, and before the tradesmen and their guilds had been established, the people of the Weald lived and worked from their settlements, they were free people who laboured for themselves and not for a feudal lord thus inheritance of family lands followed a system called Gavelkind, a concession that was granted by William the Conqueror. The origins of Gavelkind are unclear, but it has been suggested that it is taken from the Saxon word gafol meaning rent, or a 'customary performance of husbandry works' and 'therefore they called the lands, which yield this kind of service, gavelkind that is, the kind of land that yields rent.' However, legend tells us, that in 1067, when the Conqueror returned to Normandy he wished to board his ship in Dover but he had to pass through East and West Kent, the lands he’d avoided when he arrived in the previous year. Barring his way were the men of Kent. The story goes that these landholders offered William a choice, fight your way through or agree to terms each represented by a sword and a branch. Strangely, William chose the branch, and in doing so agreed that the people of Kent could have rights over their own lands. Gavelkind gave each son the right to receive an equal share of his father's land and property, this was different from the usual law of primogeniture where only the eldest son received the estate. To quote from the 13th century Custumal (a document that lists a manors tenants and the customs under which the tenants held his house and lands) as

“...if any tenant in Gavelkind die having inherited Gavelkind lands and tenements, let all the sons divide that heritage equally, and if there be no male heirs, let the partition be made among the females in the same way as among brothers. And let the messuage be divided among them, but the hearth-place shall belong to the youngest son or daughter (the others receiving the equivalent in money) and as far as forty-feet around the hearth place if the heritage will allow it. And let the eldest have the first choice of the portions and the others afterwards in that order”

It was under this law that the Hendley family held their lands in Coursehorn and we can assume that they had been living on this little piece of land since Hengest’s invasion in the 5th century.

“...if any tenant in Gavelkind die having inherited Gavelkind lands and tenements, let all the sons divide that heritage equally, and if there be no male heirs, let the partition be made among the females in the same way as among brothers. And let the messuage be divided among them, but the hearth-place shall belong to the youngest son or daughter (the others receiving the equivalent in money) and as far as forty-feet around the hearth place if the heritage will allow it. And let the eldest have the first choice of the portions and the others afterwards in that order”

It was under this law that the Hendley family held their lands in Coursehorn and we can assume that they had been living on this little piece of land since Hengest’s invasion in the 5th century.

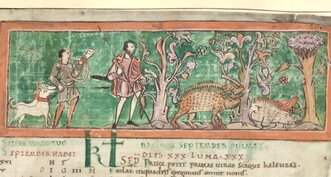

The evidence that the Hendley family may be descended from the Jutes can be found in the origins of their surname which derives from the Germanic word Hen - a domestic fowl and the suffix ley that refers to those who lived in a woodland clearing. This explanation fits nicely with what we know about the ancient people who lived in Kent at the time of the arrival of the Jutes in the year 450. These Germanic people divided the Weald into commons and used their woodlands for timber, fuel and a seasonal source of food for their animals. Taking swine into the woods to fatten them up took place in the late summer or early autumn, this right is known as pannage. Farmers like the early Hendley’s returned their pigs to the same piece of woodland every year, a woodland pig pasture was known as a den. Over time the movement of pigs back and forth formed tracks that we now refer to as droves, eventually, these dens became settlements, the Hendley’s settlement was known as Coursehorn.

Coursehorn was one of about ten dens scattered around what would later be the village of Cranbrook. These independent, as yet unnamed settlements were not classed as a manor and therefore do not appear in the Domesday Book. The bigger den of Cranbrook along with two others formed part of the Manor of Godmersham, which belonged to the Dean and Chapter of Canterbury, the other eight formed part of the Royal Manor of Wye, an ancient manor that had previously belonged to the Anglo-Saxon royal family as part of the endowment of Battle Abbey. By the end of the 14th century, Cranbrook would become a significant Kentish town, the rise of this village from an Anglo-Saxon den to the centre of the local broadcloth industry has its roots in the exporting of cloth, and Cranbrook’s importance in this and in the history of the Hendley’s should not be overlooked.

Anciently Cranbrook was known as Cranebroca, and it was not until the 15th century that it was being referred to by its present name. Cranbrook’s physical origins lie in the surrounding marshy ground of the Crane Valley, a wetland that was abundant in oak, ash and hazel trees that, according to the 18th-century antiquarian Edward Hasted, was ‘exceeding healthy, and considering the deepness of the soil, and the frequency of the woods, is far from being unpleasant.” Willow trees grew on the bank of the stream that ran through the valley and its clear water was the home of many a wading bird such as the heron and crane, it was from the latter that the village takes its name. Edward Hasted mentions in his History of Kent that in the Parish of Cranbrook there were twelve other villages, three of them, Glassenbury, Sissinghurst and Betenham would later be linked with the 15th and 16th century Hendley family. Cranbrook itself, according to an 18th-century guide book, was about half a mile in length, but before that, the village was nothing more than an area of land dotted with a few houses and as we have seen, worked by those who in an earlier time had cleared and maintained land and then claimed it by right of possession. The growth of Cranbrook, you could argue, began in the 13th century with two important grants, the first when King John made Cranbrook into a Hundred and secondly the granting of a charter by Edward I to John Peckham, the Archbishop of Canterbury which gave the village the right to hold a twice-weekly market and two annual fairs. Despite the fact there was a regular market at Cranbrook, agriculture was not the main form of employment and therefore the number of labouring poor within the community were few and with that in mind, we can only wonder what part, if any, the men of Cranbrook played in the Peasants Revolt of 1381 when it’s leader Wat Tyler is reputed to have lived in the neighbouring village of Brenchley. The village church, dedicated to St Dunstan, is by far the oldest building the village, its roots are firmly embedded in the 11th century, improvements to what was originally a small wooden church continued right up to the time of the Black Death. The aforementioned weekly market was held on a Sunday in the church’s grounds and when the day’s worship was over landholders like the Hendley’s would bring their surplus produce to the market to sell. Complaints about Sunday trading on sacred ground forced traders into the centre of town and market day, as it is today, took place during the week and this may be the reason St Dunstan’s Cross became known as Market Cross.

The first of the Hendley family that we know to have held the ancient manor of Coursehorn was Gervais Hendley, he was born at the very beginning of the 14th century.