The Farmer

The Cornwall in which Edith Mitchell was born was still remote, but not as inaccessible as it was in her grandfather's day, Cornwall was about to be permanently attached to the mainland, she was an island no longer and I wonder if the Cornish people ever thought that they may be losing more than they would gain?

In 1853 when Edith was born, it was almost sixteen years into the reign of Queen Victoria. The Georgian and Regency period was gone and Victoria was viewed in a favourable light. Although she ruled over a country that itself was stable, there was trouble abroad in the Crimea and in India. Because of the changes brought

about by the Industrial and Agricultural revolutions, Edith’s generation could expect to live a better life than that of her grandfather’s.

The Industrial Revolution changed the world we live in, but at the time, the Victorian’s wrestled with the problems it created, poor housing conditions, infectious diseases and the early deaths of the poor who inhabited England's cities. As a direct result of the wealthy, art buying, book reading Victorian, who wished not to dwell on such matters, we were brought up to think that our country living ancestors lived in a world that graced the top of chocolate boxes.

In 1853 when Edith was born, it was almost sixteen years into the reign of Queen Victoria. The Georgian and Regency period was gone and Victoria was viewed in a favourable light. Although she ruled over a country that itself was stable, there was trouble abroad in the Crimea and in India. Because of the changes brought

about by the Industrial and Agricultural revolutions, Edith’s generation could expect to live a better life than that of her grandfather’s.

The Industrial Revolution changed the world we live in, but at the time, the Victorian’s wrestled with the problems it created, poor housing conditions, infectious diseases and the early deaths of the poor who inhabited England's cities. As a direct result of the wealthy, art buying, book reading Victorian, who wished not to dwell on such matters, we were brought up to think that our country living ancestors lived in a world that graced the top of chocolate boxes.

The Victorian artist and writer had the bad habit of turning a blind eye to squalor by depicting images of an idealised family life and the innocence of childhood rather than the reality of women and children living in England’s decaying cities or the men dying of their wounds in the Crimea. As we admire these Victorian paintings, such as Myles Birkett Foster’s At the Cottage Door that is pictured here or read the words of Foster’s contemporary Dinah Craik

“After this our road turned inland. Our good horse, with the dogged persistency of Cornish horses and Cornish men, plodded on mile after mile. Sometimes for an hour or more we did not meet a living soul; then we came upon a stray labourer, or passed through a village where health-looking children, big-eyed, brown-faced, and dirty-handed, picturesque if not pretty, stared at us from cottage doors, of from the gates of cottage gardens full of flowers and apples.”

we really ought to realise that this romanticised portrayal was not how life was for our nineteenth century ancestors. However, we should have no doubt that Edith's family life on the farm at Trevemper was far better than the life of the family who lived in the slums of London, but it was still one of hard work and struggle, the Victorian artist and writer who presented these peoples lives to us as an ideal, got it very very wrong.

“After this our road turned inland. Our good horse, with the dogged persistency of Cornish horses and Cornish men, plodded on mile after mile. Sometimes for an hour or more we did not meet a living soul; then we came upon a stray labourer, or passed through a village where health-looking children, big-eyed, brown-faced, and dirty-handed, picturesque if not pretty, stared at us from cottage doors, of from the gates of cottage gardens full of flowers and apples.”

we really ought to realise that this romanticised portrayal was not how life was for our nineteenth century ancestors. However, we should have no doubt that Edith's family life on the farm at Trevemper was far better than the life of the family who lived in the slums of London, but it was still one of hard work and struggle, the Victorian artist and writer who presented these peoples lives to us as an ideal, got it very very wrong.

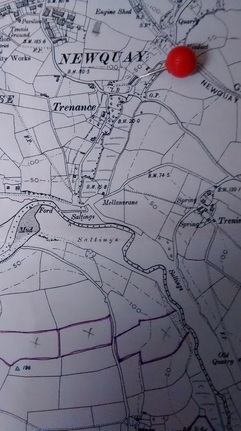

Trevemper Farm stands on the southern side of the River Ganel, only a quarter of a mile from the bridge that connected Trevemper to Newquay, a bridge that Edith’s family had crossed and recrossed since they took on the farm in 1799. Edith was the first of the Mitchell not to be born on the farm at Lesciston, she arrived at her father's thirty acre farm in the October of 1853, nine days short of her parents first wedding anniversary. Her childhood was a typical Cornish one, you can almost picture her passing through the gate you see in the photograph (the original granite gate post is still there) or playing in the fields and in the haystacks of the farm during the long Cornish summers.

At the beginning of Queen Victoria's reign, girls like Edith would not have received a decent education, but reformists were hoping that children would soon have the opportunity to learn, but this would not come about for another twenty years when there would be a school in every village and town. Until then Edith would follow in the footsteps of her ancestors, learning what she needed to know from her family and from experience.

By 1860 Edith was the only girl among four boys, the Mitchell family was complete, as the sun rose and fell and eight seasons passed the Mitchell children were oblivious to the changes that were ahead, at fourteen, I wonder what Edith was told about her father and the loss of the farm, was she old enough to realise that there was more to it than her father’s ill health? Still, his death in the October of 1868 would have been a shock and the move from the family home a great upheaval. Out of the original 90 acres of land that had been farmed by the Mitchell family since 1799 only forty acres were still tended by the family, Lescliston being farmed by Edith’s cousin Joseph Plummer. The Trevemper tenancy had been taken over by Silas Martyn of Wadebridge. Silas Martyn had four children under the age of six, and he employed one man and four boys on the farm. It is highly likely that Edith’s two brothers, William who was a carter and Samuel a farm labourer, were two of the four. Edith as a farm servant may have been employed in the Martyn household too.

By 1860 Edith was the only girl among four boys, the Mitchell family was complete, as the sun rose and fell and eight seasons passed the Mitchell children were oblivious to the changes that were ahead, at fourteen, I wonder what Edith was told about her father and the loss of the farm, was she old enough to realise that there was more to it than her father’s ill health? Still, his death in the October of 1868 would have been a shock and the move from the family home a great upheaval. Out of the original 90 acres of land that had been farmed by the Mitchell family since 1799 only forty acres were still tended by the family, Lescliston being farmed by Edith’s cousin Joseph Plummer. The Trevemper tenancy had been taken over by Silas Martyn of Wadebridge. Silas Martyn had four children under the age of six, and he employed one man and four boys on the farm. It is highly likely that Edith’s two brothers, William who was a carter and Samuel a farm labourer, were two of the four. Edith as a farm servant may have been employed in the Martyn household too.

By 1871 the family had vacated the large farm house for a tiny three roomed cottage in the nearby Trenance Valley

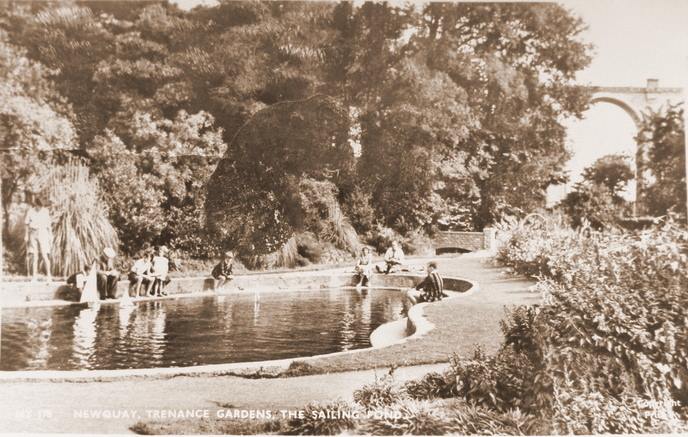

Tre-nans or "the settlement in the valley" eventually became Trenance, a marshland that was often flooded by the River Gannel at high tide. In 1086, Trenance formed part of the Manor of Treninnick. By 1327 the valley was noted has having a tiny stream, orchards and fields and was, by then, recorded as a separate settlement held by Edith’s maternal ancestors, the Arundel family of Lanherne. By the 1400’s Trenance had passed to a different branch of the family, the Arundels of Trerice and had a water mill, a dovecote and a windmill that stood on the hill above. The valley, in Edith’s time, was mainly agricultural and remained so until 1906 when the park and gardens were being developed. The gardens you see today with its tropical plants and it neatly maintained borders, its miniature railway and its zoo all appeared in time, its popular boating lake was created as an unemployment relief measure, the workers were given a pasty a day and a shilling a week to dig it out.

Tre-nans or "the settlement in the valley" eventually became Trenance, a marshland that was often flooded by the River Gannel at high tide. In 1086, Trenance formed part of the Manor of Treninnick. By 1327 the valley was noted has having a tiny stream, orchards and fields and was, by then, recorded as a separate settlement held by Edith’s maternal ancestors, the Arundel family of Lanherne. By the 1400’s Trenance had passed to a different branch of the family, the Arundels of Trerice and had a water mill, a dovecote and a windmill that stood on the hill above. The valley, in Edith’s time, was mainly agricultural and remained so until 1906 when the park and gardens were being developed. The gardens you see today with its tropical plants and it neatly maintained borders, its miniature railway and its zoo all appeared in time, its popular boating lake was created as an unemployment relief measure, the workers were given a pasty a day and a shilling a week to dig it out.

The cottages, into which the family moved are now known as Vine, Middle and Rose, they were converted from a malt house between 1851 and 1861, the Mitchell's

were probably the second family to move into Middle Cottage. When they moved in they were a family of five, a large family for such a small house. Edith would have have shared a bedroom with her mother and her three brothers would have shared the second bedroom. There were two downstairs rooms in

Middle Cottage consisting of a parlour and a kitchen. In the kitchen there was a cupboard under the stairs, in Cornwall called a Spence, a larder and a kitchen range on which Edith’s mother would cook. Edith, would return home after her duties were completed, William and Samuel would also return home, for they were not old enough to have a life away from home just yet. James John at eleven, would return after spending part of the day at school, to help with the chores. It would be nice to think that the family would all sit around a small table, eating the food that was prepared by their mother that day, and in the winter evenings spending time around the fire talking of times gone by, reading or mending clothes.

were probably the second family to move into Middle Cottage. When they moved in they were a family of five, a large family for such a small house. Edith would have have shared a bedroom with her mother and her three brothers would have shared the second bedroom. There were two downstairs rooms in

Middle Cottage consisting of a parlour and a kitchen. In the kitchen there was a cupboard under the stairs, in Cornwall called a Spence, a larder and a kitchen range on which Edith’s mother would cook. Edith, would return home after her duties were completed, William and Samuel would also return home, for they were not old enough to have a life away from home just yet. James John at eleven, would return after spending part of the day at school, to help with the chores. It would be nice to think that the family would all sit around a small table, eating the food that was prepared by their mother that day, and in the winter evenings spending time around the fire talking of times gone by, reading or mending clothes.

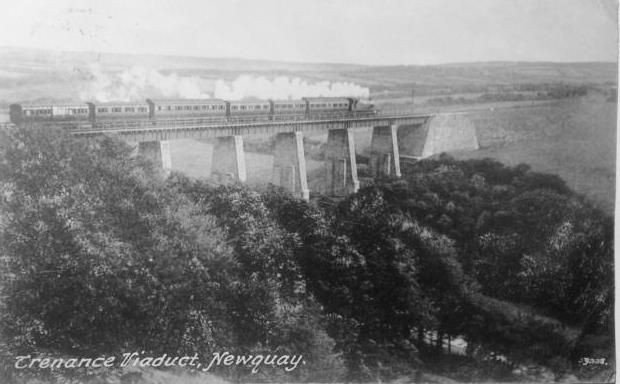

It was from this cottage, that Edith and her brothers would witness the beginnings of a major social change that, to a lesser extent, would affect the Trenance Valley itself, however it would greatly affect the neighbouring fishing village of Newquay. Joseph Treffry, a landowner, engineer and mining industrialist had purchased Newquay’s harbour, he also owned a number of mines in the area around Goss Moor. Treffry planned to link all his acquisitions with a new railway system that began with a tramway from Ponts Mill in St Blazey and ended at Newquay. This resulted, in 1849, in the timber framed viaduct, known as the Tolcarne Viaduct, but by the early 1870’s, it was replaced with a stronger granite viaduct just like the one that spanned the Luxulyan Valley. New piers and wrought iron girders were installed, the viaduct was ready for use in 1874, that year Mitchell’s had been living in Middle Cottage for six years.

At Trenance the family were together for at least two years, but how much longer after that is not known, my instinct tells me it was not that long. Following the 1871 census, Samuel Mitchell’s sons disappear, they were too young to take up farm tenancies as their ancestors had done and by the time the were old enough, the land had been incorporated into neighbouring farms. None of them married local girls or stayed in Crantock. I considered for a time that William, Samuel and James were part of the Cornish diaspora that affected the county between 1861 and 1901 were over 250,000 Cornish migrated abroad, but this, I think, is not the case. It is sad to think that these young men on whom the family name of Mitchell was dependent, faded into obscurity. Only James, aged twenty one can be found employed as a coachman in St Minver, but after that he disappears. Of William and Samuel, there is nothing, however, Edith had met Charles James Pearce, a fisherman from Newquay, and wedding plans had been made.

The Peace family were originally from Mevagissey, Charles's grandfather have moved his family to Newquay to escape the Cholera outbreak in 1849, but had moved back when it was safe to do so, his son remained. Edith’s marriage to Charles James took place at the parish church of St Columb Minor on the 13th February 1879, the witnesses being Charles's brother and sister, the lack of a Mitchell witness goes some way to back up my previous theory. Edith’s move to Newquay brought her close to family, and this may have compensated for the ‘loss’ of her own Mitchell relations. Edith's mothers family, the Clemens lived in Newquay as did her husband's family, the Pearces and the James’s.

Early Newquay has been described as a “bleak, windswept, coastal wasteland” this somewhat dramatic description is not too far from the truth for Newquay was originally a tiny coastal hamlet, with few homes. It was known in the medieval period as Towan Blystra, and was first recorded in documents in 1439. what inhabitants there were supported themselves through fishing. In the early 19th century Newquay reaped the benefits when its harbour was used, not only for fishing, but to transport goods out of the country. However Joseph Treffry’s death 1850, stopped the expansion of Newquay as a port shipping ore and china clay but it brought about a new expansion. The Victorian holiday maker arrived on Treffry's railway instead of commodities and Edith would find herself in this town about to be engulfed by the tourism industry.

Newquay soon spread eastward over the hill that divided the two parishes to encompass Trenance, from then on it would no longer be seen as a separate parish, but as pleasure garden. At this point in time, apart from the aforementioned viaduct with its pillars like giants legs straddling the valley, Trenance was still a tree covered semi wilderness, it’s boating lake, as previously mentioned was constructed in 1906 and the tennis courts in 1917. Including

Newquay's beaches, Trenance Gardens was one of Newquay's first tourist attractions.

Into the new seaside resort of Newquay flocked hundreds of Victorian and Edwardian holidaymakers, to accommodate these ‘visitors’ new hotels were built

along Narrowcliff, and so strong was the attraction that many of the wealthy purchased houses of their own to which they would bring their families and

servants at the height of the season. The visitors could be seen strolling along the Narrowcliffe and Towan Promenades, taking tea at the Atlantic or the Headland Hotels and emerging from the many bathing huts that were appearing on Newquay’s fine golden sands.

The Peace family were originally from Mevagissey, Charles's grandfather have moved his family to Newquay to escape the Cholera outbreak in 1849, but had moved back when it was safe to do so, his son remained. Edith’s marriage to Charles James took place at the parish church of St Columb Minor on the 13th February 1879, the witnesses being Charles's brother and sister, the lack of a Mitchell witness goes some way to back up my previous theory. Edith’s move to Newquay brought her close to family, and this may have compensated for the ‘loss’ of her own Mitchell relations. Edith's mothers family, the Clemens lived in Newquay as did her husband's family, the Pearces and the James’s.

Early Newquay has been described as a “bleak, windswept, coastal wasteland” this somewhat dramatic description is not too far from the truth for Newquay was originally a tiny coastal hamlet, with few homes. It was known in the medieval period as Towan Blystra, and was first recorded in documents in 1439. what inhabitants there were supported themselves through fishing. In the early 19th century Newquay reaped the benefits when its harbour was used, not only for fishing, but to transport goods out of the country. However Joseph Treffry’s death 1850, stopped the expansion of Newquay as a port shipping ore and china clay but it brought about a new expansion. The Victorian holiday maker arrived on Treffry's railway instead of commodities and Edith would find herself in this town about to be engulfed by the tourism industry.

Newquay soon spread eastward over the hill that divided the two parishes to encompass Trenance, from then on it would no longer be seen as a separate parish, but as pleasure garden. At this point in time, apart from the aforementioned viaduct with its pillars like giants legs straddling the valley, Trenance was still a tree covered semi wilderness, it’s boating lake, as previously mentioned was constructed in 1906 and the tennis courts in 1917. Including

Newquay's beaches, Trenance Gardens was one of Newquay's first tourist attractions.

Into the new seaside resort of Newquay flocked hundreds of Victorian and Edwardian holidaymakers, to accommodate these ‘visitors’ new hotels were built

along Narrowcliff, and so strong was the attraction that many of the wealthy purchased houses of their own to which they would bring their families and

servants at the height of the season. The visitors could be seen strolling along the Narrowcliffe and Towan Promenades, taking tea at the Atlantic or the Headland Hotels and emerging from the many bathing huts that were appearing on Newquay’s fine golden sands.

The lives of the wealthy holiday maker was a far cry from the life Edith would lead from her home on Deer Park in Newquay. Marrige, we hope started happily

for Edith, her first child, Sarah Jane was born exactly nine months following her wedding. Two more pregnancies in following two years resulted in the births of

Edith and Ethel, a son William was born in 1887. We know from examining the 1911 census that Edith had given birth to five children, but one it seems had

not made it through infancy, this and maybe a miscarriage before the birth of William might account for the lack of children in the five years before 1887. Sadly,

this was not the last tragedy in Edith's life, just as her mother lost had her husband at relatively young age, so did Edith. Edith’s marriage to Charles Pearce

lasted only nine years.

In the first few months of 1888 Charles began to complain that he was tired. Tiredness, for a fisherman who was out at sea for hours on end and in all weathers would, I imagine, be a common problem and maybe nothing was made of it. This fatigue was soon accompanied by a cough that did not clear but worsened,

eventually Charles developed a hacking cough that brought up blood, the local doctor would have told Edith what she probably already knew, that her husband had contracted Tuberculosis.Tuberculosis or Consumption was not an uncommon disease in the 19th century, it was sometimes called The Graveyard Cough or the Robber of Youth, and how right this was, Charles Pearce died in the March of 1888, he was just thirty two. Sadly, Charles ended his days in Bodmin lunatic asylum, it was not unknown for such places to take in those suffering from a serious illness and I can only assume that his illness was the reason he was there, it may of course be the case that there were mental issues, but as yet, I’ve been unable to confirm this. Either way Charles Pearce’s death left Edith a widow with

four children under nine years of age.

In the years following Charles’s death the family moved house at least twice and Edith was forced to find work. From their home in Ducks Alley, Edith worked

as a laundress, and following this a char woman. Edith’s elderly mother had moved from the cottage in Trenance to a house on Wesley Yard an area not too

far Ducks Alley and Deer Park. Fortunately for Edith her mother was in good health and independent. The Pearce children were growing up, Edith’s elder

daughter at the age of eleven, was living with her grandmother on Wesley Yard, Edith, Ethel and William were all living at home. The end of the 19th century

brought changes within the family. Edith, the second eldest daughter finally left home and had found employment as a servant in the home of a local dentist.

It also brought a pregnancy that ended in the birth of a boy in 1897.

This boys name was John Thomas, and on the 1901 and 1911 census Edith states that he was a ‘guest.’ It is commonly thought that on the day of the

census the enumerator would visit each household and take down all information personally, this was not the case. A few days before he would deliver what was known as a Household Schedule and the head of the household would fill it in, on the day of the census he would return, check and collect them. If the

members of the household were illiterate then the enumerator would fill the form in for them. Edith was not illiterate, she made the conscious decision to

deceive and hide the real relationship with this child. This boy was not a guest, why would a poor widow woman, who took in laundry, who scrubbed

and cleaned for others to keep her family's head above water, take on another child who was not her own? She wouldn’t. It is my belief that John, or

Jack (Huxtable) as he was known within our family was either the son of Edith or her elder daughter Sarah Ann. Whoever bore this child never acknowledged

the fact on paper, either on the censuses as we have just seen, or even to the registrar despite the fact there was hefty fine for not doing so.

for Edith, her first child, Sarah Jane was born exactly nine months following her wedding. Two more pregnancies in following two years resulted in the births of

Edith and Ethel, a son William was born in 1887. We know from examining the 1911 census that Edith had given birth to five children, but one it seems had

not made it through infancy, this and maybe a miscarriage before the birth of William might account for the lack of children in the five years before 1887. Sadly,

this was not the last tragedy in Edith's life, just as her mother lost had her husband at relatively young age, so did Edith. Edith’s marriage to Charles Pearce

lasted only nine years.

In the first few months of 1888 Charles began to complain that he was tired. Tiredness, for a fisherman who was out at sea for hours on end and in all weathers would, I imagine, be a common problem and maybe nothing was made of it. This fatigue was soon accompanied by a cough that did not clear but worsened,

eventually Charles developed a hacking cough that brought up blood, the local doctor would have told Edith what she probably already knew, that her husband had contracted Tuberculosis.Tuberculosis or Consumption was not an uncommon disease in the 19th century, it was sometimes called The Graveyard Cough or the Robber of Youth, and how right this was, Charles Pearce died in the March of 1888, he was just thirty two. Sadly, Charles ended his days in Bodmin lunatic asylum, it was not unknown for such places to take in those suffering from a serious illness and I can only assume that his illness was the reason he was there, it may of course be the case that there were mental issues, but as yet, I’ve been unable to confirm this. Either way Charles Pearce’s death left Edith a widow with

four children under nine years of age.

In the years following Charles’s death the family moved house at least twice and Edith was forced to find work. From their home in Ducks Alley, Edith worked

as a laundress, and following this a char woman. Edith’s elderly mother had moved from the cottage in Trenance to a house on Wesley Yard an area not too

far Ducks Alley and Deer Park. Fortunately for Edith her mother was in good health and independent. The Pearce children were growing up, Edith’s elder

daughter at the age of eleven, was living with her grandmother on Wesley Yard, Edith, Ethel and William were all living at home. The end of the 19th century

brought changes within the family. Edith, the second eldest daughter finally left home and had found employment as a servant in the home of a local dentist.

It also brought a pregnancy that ended in the birth of a boy in 1897.

This boys name was John Thomas, and on the 1901 and 1911 census Edith states that he was a ‘guest.’ It is commonly thought that on the day of the

census the enumerator would visit each household and take down all information personally, this was not the case. A few days before he would deliver what was known as a Household Schedule and the head of the household would fill it in, on the day of the census he would return, check and collect them. If the

members of the household were illiterate then the enumerator would fill the form in for them. Edith was not illiterate, she made the conscious decision to

deceive and hide the real relationship with this child. This boy was not a guest, why would a poor widow woman, who took in laundry, who scrubbed

and cleaned for others to keep her family's head above water, take on another child who was not her own? She wouldn’t. It is my belief that John, or

Jack (Huxtable) as he was known within our family was either the son of Edith or her elder daughter Sarah Ann. Whoever bore this child never acknowledged

the fact on paper, either on the censuses as we have just seen, or even to the registrar despite the fact there was hefty fine for not doing so.

In 1911, three of Edith’s four children were married and had children of their own, Edith was living on Sidney Road, just a few doors away from William,

her newly married son. Edith was fifty six, and living with her was thirteen year old Jack.

Sydney Road looked out over what was called the Whim. The wagons with their load of china clay arrived at the Whim after they had passed over Treffry’s viaduct

in the Trenance Valley. They were brought into Newquay railway station by steam engines, and then pulled along the tramway by horses, and would exit via a steeply inclined tunnel onto the harbour. The winding mechanism for this tunnel was powered by two stationary engines that were housed in the Whim. It is

interesting that from her home in Trenance Cottages, Edith would have seen the first part of the wagons journey as they arrived in Newquay when they passed

over the viaduct, and years later from her window on Sydney Road, Edith would be able to see where the wagon's journey ended.

Edith's house on Sydney Road was more or less opposite Alma Place, it was a move into one of the small terraced houses here that would be her last.

The houses on Alma Place are thought to be among the twelve houses William Borlase mentions in his 1769 publication The Antiquities of Cornwall.

In this work the Cornish antiquary wrote of his visit in 1755.

“‘Passed the Ganel and went about a mile further to a place of about twelve houses called Towen Blystra, a furlong further to the New Quay in St Columb Parish,

here is a little pier, the north point of which is fixed on a rock, the end in a cliff, at the eastern end there is a gap cutt about 25 feet wide into the slatty rock

of the cliff. This gap lets small ships into a basin which may hold about six ships of about 80 tons burthen and at spring tides has 18 feet of water in it,

upon the brow of the cliff is a dwelling house and a commodious cellar lately built.”

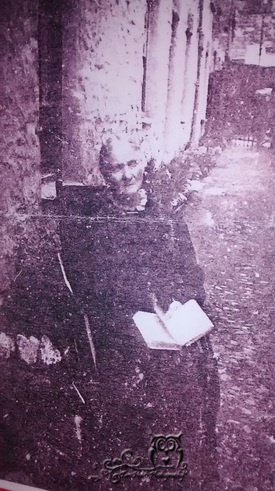

It is at Alma Place that we can see, for the first time, what Edith looked like, I believe this photo was taken not long before her death in 1922. In my photograph she is dressed in a dark dress and sits in a rocking chair with a book on her lap, she looks tired, and a lot older than her 69 years. Edith, I believe, may have been recovering from a stroke, my grandfather remembers that she had no movement in one of her arms and that it hung loosely at her side.

her newly married son. Edith was fifty six, and living with her was thirteen year old Jack.

Sydney Road looked out over what was called the Whim. The wagons with their load of china clay arrived at the Whim after they had passed over Treffry’s viaduct

in the Trenance Valley. They were brought into Newquay railway station by steam engines, and then pulled along the tramway by horses, and would exit via a steeply inclined tunnel onto the harbour. The winding mechanism for this tunnel was powered by two stationary engines that were housed in the Whim. It is

interesting that from her home in Trenance Cottages, Edith would have seen the first part of the wagons journey as they arrived in Newquay when they passed

over the viaduct, and years later from her window on Sydney Road, Edith would be able to see where the wagon's journey ended.

Edith's house on Sydney Road was more or less opposite Alma Place, it was a move into one of the small terraced houses here that would be her last.

The houses on Alma Place are thought to be among the twelve houses William Borlase mentions in his 1769 publication The Antiquities of Cornwall.

In this work the Cornish antiquary wrote of his visit in 1755.

“‘Passed the Ganel and went about a mile further to a place of about twelve houses called Towen Blystra, a furlong further to the New Quay in St Columb Parish,

here is a little pier, the north point of which is fixed on a rock, the end in a cliff, at the eastern end there is a gap cutt about 25 feet wide into the slatty rock

of the cliff. This gap lets small ships into a basin which may hold about six ships of about 80 tons burthen and at spring tides has 18 feet of water in it,

upon the brow of the cliff is a dwelling house and a commodious cellar lately built.”

It is at Alma Place that we can see, for the first time, what Edith looked like, I believe this photo was taken not long before her death in 1922. In my photograph she is dressed in a dark dress and sits in a rocking chair with a book on her lap, she looks tired, and a lot older than her 69 years. Edith, I believe, may have been recovering from a stroke, my grandfather remembers that she had no movement in one of her arms and that it hung loosely at her side.

It was not long before Edith was ill again, she began to suffer from abdominal pain and was taken to the Royal Cornwall Infirmary in Truro where she

underwent surgery for a strangulated femoral hernia, it was also discovered that he had a ruptured bowel. Following the surgery, Edith went into what is

called operation shock and died on the 11th October 1922, aged sixty nine.

On Edith death she left three grandchildren, one of which was my grandfather, he recalled that on the day of her funeral her coffin was carried on a horse

drawn cart from Alma Place along Fore Street, through to Central Square, up Crantock Street and into the Tower Road Cemetery.

underwent surgery for a strangulated femoral hernia, it was also discovered that he had a ruptured bowel. Following the surgery, Edith went into what is

called operation shock and died on the 11th October 1922, aged sixty nine.

On Edith death she left three grandchildren, one of which was my grandfather, he recalled that on the day of her funeral her coffin was carried on a horse

drawn cart from Alma Place along Fore Street, through to Central Square, up Crantock Street and into the Tower Road Cemetery.

I often wonder what sort of life William Mitchell envisaged for his eight children? Did he hope that they would aspire to greater things or did he just wish to

seehis family expanding with his sons carrying the name of Mitchell forward. Sadly, none of these things came to be, within two generations

there was no one bearing the name of Mitchell living in the Crantock area or in Newquay. In 1868, when William's son Samuel went to his grave he took

the surname of Mitchell with him, thus ending the male line.

Edith was the last of the family to bear that name.

The Mitchell DNA continues through the Pearce family and of course through to me. A hundred and forty six years after Edith moved into her new home at

Trenance Cottage, and ninety four years after her death here, playing on her doorstep at Middle Cottage in Trenance Gardens is her 4x great grandson.