|

John Henry Taylor

Great Grandfather |

John Henry's birth was registered in the May of 1878 in the Staffordshire district of Kingswinford, his surname of Kennett was his mother's family name, his father was unknown. John Henry was born one month earlier in April on Potter Street, Brierley Hill. At the time of his birth his mother was employed as a Pit Bank Labourer, an arduous job only done by women, these women would pick what was known as “pennystone” from the pit banks in the ironstone mines, for which she was paid on average eight shillings a week, hardly any money to be able to keep a herself and a new baby, but by the time of John Henry's birth his mother had already given birth to an elder sister, Alice Elizabeth. By 1880 Eliza was pregnant again and had moved her two children into a house on Chapel Street, she had also changed her job and was now a labourer in the local brickyard, chances are that Eliza struggled to pay her rent and was evicted from her home, John Henry would have been just three years old when Sarah Ann was born, too young to know what was going on in his mothers life.

Moving onto Potter Street with Joseph Taylor was most certainly a lifeline for John, his mother's past history with men and unpaid rent meant that she would have been unable to financially support her children and may have had to face the difficult decision to keep the children or turn them over to another’s care or worse still the workhouse. John must have looked up to Joseph Taylor for he would have been the first man who showed him what it was like to have a father.

The house on Potter Street would have been very small and cheaply built, family homes like this had between two and four rooms - one or two rooms downstairs, and one or two rooms upstairs, as we have previously seen. Victorian families at that time were big with perhaps 4-5 children, with the arrival of the Kennett’s into the Taylor household there were a total of seven people in the house. There was no water, and no inside toilet. A whole street (sometimes more) would have to share a couple of toilets and a pump. The water from the communal pump was frequently polluted and it was no surprise that few children made it to adulthood. Some of the worst houses were ‘back to backs’ or built on courts, the only windows were at the front. There were no backyards and a sewer ran down the middle of the street. Housing conditions like this were perfect breeding grounds for disease and John and his sisters were lucky they had a resourceful mother and a man who was willing to share his home.

Moving onto Potter Street with Joseph Taylor was most certainly a lifeline for John, his mother's past history with men and unpaid rent meant that she would have been unable to financially support her children and may have had to face the difficult decision to keep the children or turn them over to another’s care or worse still the workhouse. John must have looked up to Joseph Taylor for he would have been the first man who showed him what it was like to have a father.

The house on Potter Street would have been very small and cheaply built, family homes like this had between two and four rooms - one or two rooms downstairs, and one or two rooms upstairs, as we have previously seen. Victorian families at that time were big with perhaps 4-5 children, with the arrival of the Kennett’s into the Taylor household there were a total of seven people in the house. There was no water, and no inside toilet. A whole street (sometimes more) would have to share a couple of toilets and a pump. The water from the communal pump was frequently polluted and it was no surprise that few children made it to adulthood. Some of the worst houses were ‘back to backs’ or built on courts, the only windows were at the front. There were no backyards and a sewer ran down the middle of the street. Housing conditions like this were perfect breeding grounds for disease and John and his sisters were lucky they had a resourceful mother and a man who was willing to share his home.

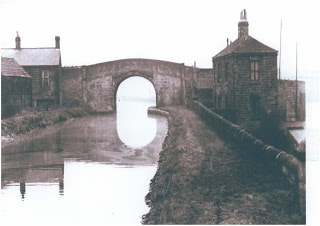

In the early 1800's, many children worked a 16-hour days in atrocious conditions alongside their parents from the age of five, by 1841 the Mines Act stated that no child under the age of ten were to work underground in a coal mine, and by 1880 schooling was mandatory and all children had to attend school until they were ten years old. In 1889, the school leaving age was raised to twelve, and in 1891 schooling was free. John Henry would have been one of the first group of children not to spend his childhood underground and have a chance of an education. According to John Henry’s daughter Annie, the house in which they lived was a stone house by the canal in Royston much like the one seen below.

The population of Royston had increased dramatically with an influx of men looking for work in the new deep mines. The Taylor family, like many others, wanted a better life for themselves and John Henry had the stability of a family who were in paid employment with a home. By 1891, John Henry was thirteen and was attending the local school, living with him at Monkton Row were his parents Joseph and Eliza, his two elder sisters Alice and Sarah, his three year old sister Edith and younger brother Ernest, also in the house was William Black a colliery labourer from Kinswinford.

As soon as he left school John Henry began work at Monckton Colliery where he was as a employed as a coal hewer. The following extract is taken from the Museum of Mining and describes the job of a Hewer in 1892:

“ The hewer is the actual coal-digger. Whether the seam be so thin that he can hardly creep into it on hands and knees, or whether it be thick enough for him to stand upright, he is the responsible workman who loosens the coal from the bed. The hewers are divided into "fore-shift" and "back-shift" men. The former usually work from four in the morning till ten, and the latter from ten till four. Each man works one week in the fore-shift and one week in the back-shift, alternately. Every man in the fore-shift marks "3" on his door. This is the sign for the "caller" to wake him at that hour. When roused by that important functionary he gets up and dresses in his pit clothes, which consist of a loose jacket, vest, and knee breeches, all made of thick white flannel; long stockings, strong shoes, and a close fitting, thick leather cap. He then takes a piece of bread and water, or a cup of coffee, but never a full meal. Many prefer to go to work fasting. With a tin bottle full of cold water or tea, a piece of bread, which is called his bait, his Davy lamp, and "baccy-box," he says good-bye to his wife and speeds off to work. Placing himself in the cage, he is lowered to the bottom of the shaft, where he lights his lamp and proceeds "in by," to a place appointed to meet the deputy. This official examines each man's lamp, and, if found safe, returns it locked to the owner. Each man then finding from the deputy that his place is right, proceeds onwards to his cavel†, his picks in one hand, and his lamp in the other. He travels thus a distance varying from 100 to 600 yards. Sometimes the roof under which he has to pass is not more than three feet high. To progress in this space the feet are kept wide apart, the body is bent at right angles with the hips, the head is held well down, and the face is turned forward. Arrived at his place he undresses and begins by hewing out about fifteen inches of the lower part of the coal. He thus undermines it, and the process is called kirving. The same is done up the sides. This is called nicking. The coal thus hewn is called small coal, and that remaining between the kirve and the nicks is the jud or top, which is either displaced by driving in wedges, or is blasted down with gunpowder. It then becomes the roundy. The hewer fills his tubs, and continues thus alternately hewing and filling.”

Coal production began at Monckton main pit in 1878 and by 1903 1721 men were employed, by 1940 it employed 4023 men and twenty years later the pit was totally abandoned. John Henry probably worked at Monckton Colliery all his life and it was during his first three years there that he met Hannah Barraclough, the twenty-five year old daughter of Abraham Barraclough, a colliery blacksmith of Ryhill. By the time John Henry and Hannah were married Hannah was six months pregnant. At his marrige John Henry named Joseph as his father, we do not know if he knew Joseph was not his biological father but it was more than likely the did not.

By the end of July of that year he became a father for the first time to a son whom they named Arthur. John, Hannah and Arthur began their family life in Hannah’s family home, that of her widowed father at 9 Station Road Ryhill, a four roomed terraced house pictured below. Also living at this house on Station Road were Hannah’s four teenage brotherswho, like nearly all the male population of Ryhill, were employed at Monckton Colliey.

As soon as he left school John Henry began work at Monckton Colliery where he was as a employed as a coal hewer. The following extract is taken from the Museum of Mining and describes the job of a Hewer in 1892:

“ The hewer is the actual coal-digger. Whether the seam be so thin that he can hardly creep into it on hands and knees, or whether it be thick enough for him to stand upright, he is the responsible workman who loosens the coal from the bed. The hewers are divided into "fore-shift" and "back-shift" men. The former usually work from four in the morning till ten, and the latter from ten till four. Each man works one week in the fore-shift and one week in the back-shift, alternately. Every man in the fore-shift marks "3" on his door. This is the sign for the "caller" to wake him at that hour. When roused by that important functionary he gets up and dresses in his pit clothes, which consist of a loose jacket, vest, and knee breeches, all made of thick white flannel; long stockings, strong shoes, and a close fitting, thick leather cap. He then takes a piece of bread and water, or a cup of coffee, but never a full meal. Many prefer to go to work fasting. With a tin bottle full of cold water or tea, a piece of bread, which is called his bait, his Davy lamp, and "baccy-box," he says good-bye to his wife and speeds off to work. Placing himself in the cage, he is lowered to the bottom of the shaft, where he lights his lamp and proceeds "in by," to a place appointed to meet the deputy. This official examines each man's lamp, and, if found safe, returns it locked to the owner. Each man then finding from the deputy that his place is right, proceeds onwards to his cavel†, his picks in one hand, and his lamp in the other. He travels thus a distance varying from 100 to 600 yards. Sometimes the roof under which he has to pass is not more than three feet high. To progress in this space the feet are kept wide apart, the body is bent at right angles with the hips, the head is held well down, and the face is turned forward. Arrived at his place he undresses and begins by hewing out about fifteen inches of the lower part of the coal. He thus undermines it, and the process is called kirving. The same is done up the sides. This is called nicking. The coal thus hewn is called small coal, and that remaining between the kirve and the nicks is the jud or top, which is either displaced by driving in wedges, or is blasted down with gunpowder. It then becomes the roundy. The hewer fills his tubs, and continues thus alternately hewing and filling.”

Coal production began at Monckton main pit in 1878 and by 1903 1721 men were employed, by 1940 it employed 4023 men and twenty years later the pit was totally abandoned. John Henry probably worked at Monckton Colliery all his life and it was during his first three years there that he met Hannah Barraclough, the twenty-five year old daughter of Abraham Barraclough, a colliery blacksmith of Ryhill. By the time John Henry and Hannah were married Hannah was six months pregnant. At his marrige John Henry named Joseph as his father, we do not know if he knew Joseph was not his biological father but it was more than likely the did not.

By the end of July of that year he became a father for the first time to a son whom they named Arthur. John, Hannah and Arthur began their family life in Hannah’s family home, that of her widowed father at 9 Station Road Ryhill, a four roomed terraced house pictured below. Also living at this house on Station Road were Hannah’s four teenage brotherswho, like nearly all the male population of Ryhill, were employed at Monckton Colliey.

Hannah soon gave birth to another two children, a son Samuel and then daughter Annie. We have just seen how cramped the living conditions were for the family with six other people living in four rooms, but by the time of the census taken things had got much worse. The family were still living on Station Road but this time the house had six rooms, either the family had moved to a ‘bigger’ house or there was an error in what was construed as a “room”. Either way space within the house was extremely tight and must have been miserable for John Henry, who was by now thirty two, but it must have been unbearable for Hannah. In the April of 1911, there were thirteen people, eight adults and five children living in a six roomed house!

The arrival of the first world war had seen many of the young men of Royston volunteer for war, we know John Henry's maternal uncle went but John Henry did not. Thankfully, he fitted two exception criteria of conscription: a reserved occupation and a married man with a young family. However, men like John Henry did not get off lightly, an increased work load lead to longer hours in conditions that were arduous and exhausting. When his contemporaries were dealing with incendiary devices, weapons and mustard gas, John Henry was dealing with dangers just as frightening. Mining hazards include suffocation, gas poisoning, roof collapse and gas explosions, any one of these dangers could occur regularly and it was while John Henry was underground that he received a life threatening blow to his face. It is not known exactly what or when this occurred but he lost an eye. Following this accident, John Henry returned to work as a colliery surface worker, a safer job but none the less requiring much physical effort. How he coped with this awful injury is not known, one can only hope that his Barraclough brothers in law pulled their weight, but they were known to be fiery and demanding so we can only imagine that life must have been extremely difficult for John Henry.

1913 saw the marriage of Hannah’s brother David and his move away from home and the birth of son George. 1914 brought the death of his father in law and by 1917 there were two more mouths to feed in the shape of William born in 1915 and Lily in 1917. The birth records of the last three children show that the family had moved to the neighbouring village of Hemsworth which was another mining community.

How long the Taylor’s stayed in Hemsworth is not known but there were no signs of the three remaining Barraclough brothers marrying and moving on and with their own children growing into adults John Henry and Hannah were forced to spend the next twelve years in a house with ten other adults. In 1925 the new Moncton Colliery was sunk in Havercroft, and this may have been the reason for the families next move. The Taylor girls were soon married and the only son who married was George. The remaining three sons continued to live with their parents along with William, Freddy and Samuel Barraclough.

By the mid 1930's the government passed a housing act, this gave local authorities permission to demolish unsafe properties and those that were a danger to health, in doing so they had to re house tenants, and this opened the way for the building of new council estates across the whole of the country. It was into one of these properties that John Henry and Hannah finally moved and once again every body else went with them. As with many families of this time, John Henry and Hannah never had the luxury of a life on their own, from the day he was born he never lived with less than six other people. John Henry lived in Havercroft for the rest of his life continuing as a surface worker, but the last few years of heavy work hauling trolleys full of coal must have taken there toll, John Henry died from Broncho Pneumonia, Chronic Bronchitis and Arterio Scleroisis, just what you might expect from a man who spent nearly fifty years in mining.

John Henry never went by the name of just John, he was always spoken of as John Henry, his life was much influenced and in a lot of ways mimicked that of his 'father' Joseph Taylor. He was said to have been a small, quiet, unassuming man.

The arrival of the first world war had seen many of the young men of Royston volunteer for war, we know John Henry's maternal uncle went but John Henry did not. Thankfully, he fitted two exception criteria of conscription: a reserved occupation and a married man with a young family. However, men like John Henry did not get off lightly, an increased work load lead to longer hours in conditions that were arduous and exhausting. When his contemporaries were dealing with incendiary devices, weapons and mustard gas, John Henry was dealing with dangers just as frightening. Mining hazards include suffocation, gas poisoning, roof collapse and gas explosions, any one of these dangers could occur regularly and it was while John Henry was underground that he received a life threatening blow to his face. It is not known exactly what or when this occurred but he lost an eye. Following this accident, John Henry returned to work as a colliery surface worker, a safer job but none the less requiring much physical effort. How he coped with this awful injury is not known, one can only hope that his Barraclough brothers in law pulled their weight, but they were known to be fiery and demanding so we can only imagine that life must have been extremely difficult for John Henry.

1913 saw the marriage of Hannah’s brother David and his move away from home and the birth of son George. 1914 brought the death of his father in law and by 1917 there were two more mouths to feed in the shape of William born in 1915 and Lily in 1917. The birth records of the last three children show that the family had moved to the neighbouring village of Hemsworth which was another mining community.

How long the Taylor’s stayed in Hemsworth is not known but there were no signs of the three remaining Barraclough brothers marrying and moving on and with their own children growing into adults John Henry and Hannah were forced to spend the next twelve years in a house with ten other adults. In 1925 the new Moncton Colliery was sunk in Havercroft, and this may have been the reason for the families next move. The Taylor girls were soon married and the only son who married was George. The remaining three sons continued to live with their parents along with William, Freddy and Samuel Barraclough.

By the mid 1930's the government passed a housing act, this gave local authorities permission to demolish unsafe properties and those that were a danger to health, in doing so they had to re house tenants, and this opened the way for the building of new council estates across the whole of the country. It was into one of these properties that John Henry and Hannah finally moved and once again every body else went with them. As with many families of this time, John Henry and Hannah never had the luxury of a life on their own, from the day he was born he never lived with less than six other people. John Henry lived in Havercroft for the rest of his life continuing as a surface worker, but the last few years of heavy work hauling trolleys full of coal must have taken there toll, John Henry died from Broncho Pneumonia, Chronic Bronchitis and Arterio Scleroisis, just what you might expect from a man who spent nearly fifty years in mining.

John Henry never went by the name of just John, he was always spoken of as John Henry, his life was much influenced and in a lot of ways mimicked that of his 'father' Joseph Taylor. He was said to have been a small, quiet, unassuming man.

It is sad to say that even though some of these family members were alive within my life time, I know less about them that the ancestors that had gone before. Although John Henry's wife Hannah is said to have been tiny and quiet, she was not unlike her mother in law in temperament. She too was strong willed and feisty and knew exactly what she wanted, and like Eliza Kennett, got it.

The children from their marriage were; Arthur, Samuel, George and William and three daughters who I have chosen not to write about in fairness to my living relatives.

The children from their marriage were; Arthur, Samuel, George and William and three daughters who I have chosen not to write about in fairness to my living relatives.

- Arthur, was born in 1904 and lived with his parents all his life working as a coal miner, he never married and died after 1951.

- Samuel was born two years later in 1906. During the Second World War he enlisted in the army and was known to have been part of Battle of Monte Cassino as Batman to the noted pianist Gerald Moore. Moore was an English pianist best known for his career as one of the most in-demand accompanists of his day, accompanying many of the world's most famous musicians. He accompanied notable instrumentalists such as Pablo Casals. As a commissioned officer in the Second World War Moore was assigned his own Batman, a soldier chosen personally from his own men. Moore would have chosen Samuel because he must have been a trustworthy, loyal, hardworking soldier. With a position like this Samuel would have been exempt from more onerous duties and would have received better rations and other favours. Senior officers' batmen usually received fast promotion to a higher rank, but we do not know if this applied to Samuel. Samuels army records have proved difficult to locate, no evidence of his career has been found but I am sure that this family story is true. I have been told that Samuel probably enlisted as part of the 6th Battalion of The York and Lancaster Regiment.

In 1943 the 6th Battalion was part of the 46th Infantry Division, who in 1943 and until the end of the war fought with the Eighth Army in Italy.

“The Eighth Army participated in the Italian Campaign which began withOperation Husky, the invasion of the island of Sicily by Eighth Army and U.S. Seventh Army. When the Allies subsequently invaded mainland Italyelements of Eighth Army landed in the 'toe' of Italy in Operation Baytownand at Taranto in Operation Slapstick. After linking its left flank with the US Fifth Army which had landed at Salerno on the west coast of Italy south of Naples, Eighth Army continued fighting its way up Italy on the eastern flank of the Allied forces. At the end of 1943 General Montgomery was transferred to Britain to begin preparations for theNormandy invasion. Command of the Eighth Army was given to Lieutenant General Oliver Leese. Following three unsuccessful attempts in early 1944 by US Fifth Army to break through the German Winter Line, the Eighth Army was covertly switched from the Adriatic coast in April 1944 to concentrate all forces, except the V Corps, on the western side of the Apennine Mountains alongside US Fifth Army in order to mount a major offensive with them and punch through to Rome. This fourthBattle of Monte Cassino was successful with Eighth Army breaking into central Italy and Fifth Army entering Rome in early June.

Samuel certainly saw action during his career but chose not to talk about it. He did however, whilst serving in Italy, meet a young Italian girl with whom he fell in love and intended to marry. He arrived home to Yorkshire and informed his family of his plans, his mother was, by all accounts furious, and refused to let him marry her and forbade him not to return to her in Italy, he did as he was told. Samuel died unmarried in 1954.

Both Eliza Kennett’s and Hannah Barraclough's male offspring fared no better than their father and grandfather as both mothers it seems had total control of the seven sons they had between them. Out of Eliza’s three and Hannah’s four sons only two married. We have heard Eliza’s son Ernest was forced/persuaded to take the place of his brother when he was called to fight in the war and died because of it and Hannah’s son Samuel, was firmly told that he could not marry the Italian girl of his dreams, instead he died unmarried and at home with his mother just like that of his remaining male maternal uncle and his three brothers. All the Taylor daughters lives were totally different, marriage which gave them support away from the family home. Was it nature or nurture that made these two women what they were? Of Elizas life I know little before the birth of her first daughter and Hannah lived all her life surrounded by men who were dependent on her. To be fair to them life was so much harder than it is for us, it must have been a case of fight or flounder, whatever it was it certainly impacted on the lives of the Taylor men. Both Joseph and John Henry Taylor were strong characters in their own way, John Henry was a quite man, perhaps he learnt that from Joseph, maybe he 'inherited' his gentleness too?

Of John Henry's daughters only one seemed to be like her mother and grandmother the others inherited their fathers quietness and unassuming nature, turning it into contentment and well being which is apparent in many of us. Of course, the blood of the unknown man who fathered John Henry Taylor flows through our veins along with his DNA giving us some of our physical features and personalities, but its Josephs influence that stands out the most.

All works © Andrea Povey 2014. Please do not reproduce without the expressed consent of Andrea Povey.

“The Eighth Army participated in the Italian Campaign which began withOperation Husky, the invasion of the island of Sicily by Eighth Army and U.S. Seventh Army. When the Allies subsequently invaded mainland Italyelements of Eighth Army landed in the 'toe' of Italy in Operation Baytownand at Taranto in Operation Slapstick. After linking its left flank with the US Fifth Army which had landed at Salerno on the west coast of Italy south of Naples, Eighth Army continued fighting its way up Italy on the eastern flank of the Allied forces. At the end of 1943 General Montgomery was transferred to Britain to begin preparations for theNormandy invasion. Command of the Eighth Army was given to Lieutenant General Oliver Leese. Following three unsuccessful attempts in early 1944 by US Fifth Army to break through the German Winter Line, the Eighth Army was covertly switched from the Adriatic coast in April 1944 to concentrate all forces, except the V Corps, on the western side of the Apennine Mountains alongside US Fifth Army in order to mount a major offensive with them and punch through to Rome. This fourthBattle of Monte Cassino was successful with Eighth Army breaking into central Italy and Fifth Army entering Rome in early June.

Samuel certainly saw action during his career but chose not to talk about it. He did however, whilst serving in Italy, meet a young Italian girl with whom he fell in love and intended to marry. He arrived home to Yorkshire and informed his family of his plans, his mother was, by all accounts furious, and refused to let him marry her and forbade him not to return to her in Italy, he did as he was told. Samuel died unmarried in 1954.

- George Taylor born in the March of 1913 and was the only son to marry. His wife was a strict catholic. The family story goes that she spent all their married life trying to convert him to Catholicism, he spent all his life avoiding the issue.

- William Taylor was the last son to be born to John Henry and Hannah. Born in the beginning of 1915 and like his brothers never married and again like his brothers he had a temper, once through a pint pot which hit his mother breaking her nose.

Both Eliza Kennett’s and Hannah Barraclough's male offspring fared no better than their father and grandfather as both mothers it seems had total control of the seven sons they had between them. Out of Eliza’s three and Hannah’s four sons only two married. We have heard Eliza’s son Ernest was forced/persuaded to take the place of his brother when he was called to fight in the war and died because of it and Hannah’s son Samuel, was firmly told that he could not marry the Italian girl of his dreams, instead he died unmarried and at home with his mother just like that of his remaining male maternal uncle and his three brothers. All the Taylor daughters lives were totally different, marriage which gave them support away from the family home. Was it nature or nurture that made these two women what they were? Of Elizas life I know little before the birth of her first daughter and Hannah lived all her life surrounded by men who were dependent on her. To be fair to them life was so much harder than it is for us, it must have been a case of fight or flounder, whatever it was it certainly impacted on the lives of the Taylor men. Both Joseph and John Henry Taylor were strong characters in their own way, John Henry was a quite man, perhaps he learnt that from Joseph, maybe he 'inherited' his gentleness too?

Of John Henry's daughters only one seemed to be like her mother and grandmother the others inherited their fathers quietness and unassuming nature, turning it into contentment and well being which is apparent in many of us. Of course, the blood of the unknown man who fathered John Henry Taylor flows through our veins along with his DNA giving us some of our physical features and personalities, but its Josephs influence that stands out the most.

All works © Andrea Povey 2014. Please do not reproduce without the expressed consent of Andrea Povey.