|

Alice Mohun

22nd Great Grandmother 1225 - 1283 |

No Meek Subservient She!

The Mohun family had benefited by siding with King John, their closeness to those who ran the country paved the way for an advantageous marriage. The Mohun's had as a family member and ally William Brewer who had himself flourished in royal service under King John.

This new generation of Mohuns were born into a world that was being shaped by John's famous charter.

This new generation of Mohuns were born into a world that was being shaped by John's famous charter.

If the story of King John losing the royal treasure in the murky, muddy waters of the Wash in Lincolnshire is to be believed, then the royal crown of England still lies there today, in reality, whether this crown of England was lost, stolen or sold, in 1220, Henry III of England was crowned for the second time, with a brand new shiny one. With a new and young king on the throne, the populous looked forward to a monarch governing the country with a fair, but firm hand. However, by 1237 his reign was being undermined by many of his powerful barons. The troubles that had begun in the reign of King Stephen, had continued to rumbling on, although controlled under Henry II, had soon flared up once more under his father King John.

Henry, as did previous monarchs regularly used council meetings to discuss affairs of state, in Henry’s reign these meeting resulted in the early formation of an English Parliament. During the thirteenth century these assemblies were always summoned by the king and generally he consulted only a small council, but by requiring the wealthy barons to help govern, Henry strengthened their powers and in time they came to call themselves the Great Council. These men grew to think that the king must consult the council and when decisions were made without their consultation they developed a sense of being excluded from the work of government in which they felt entitled to participate.

Henry, as did previous monarchs regularly used council meetings to discuss affairs of state, in Henry’s reign these meeting resulted in the early formation of an English Parliament. During the thirteenth century these assemblies were always summoned by the king and generally he consulted only a small council, but by requiring the wealthy barons to help govern, Henry strengthened their powers and in time they came to call themselves the Great Council. These men grew to think that the king must consult the council and when decisions were made without their consultation they developed a sense of being excluded from the work of government in which they felt entitled to participate.

The king insisted that attendance at sessions of the ‘great council’ were compulsory and that it was a duty not a privilege and this, inevitably, ended in trouble. Many of Henry’s barons had become a law unto themselves and they were now seeing Henry as weak, David Carpenter writes that Henry

“failed as a ruler due to his naivety and inability to produce realistic plans for reform.”

Henry did not help himself either, his personal extravagances had resulted in large taxes and a major fall out with his brother in law and one time friend Simon de Montfort did not help matters.

Montfort was French by birth and a year younger than Henry. In 1248 Henry had appointed Montfort as Governor of Gascony, a mistake that cost Henry dearly. In Gascony, Montfort was disliked, but he was powerful and he abused his position and this forced Henry to intervene. On Montforts return to England, he too perceived Henry as weak and with the barons aching for a fight, it was Simon de Montfort that stepped in to take charge. In 1258 this action culminated in the Provisions of Oxford, a law that served to limit Henry’s power. Henry’s refusal to accept the Provisions of Westminster the following year saw Montfort’s power base grow rapidly, and by 1263 he was all but wearing the crown.

Alice Mohun was not only born into a world on the brink of conflict, but a world where the bible wrote that Eve was created from Adam's rib and, having eaten the forbidden fruit, was blamed for man's banishment from paradise. In this religion based society, women took the blame for the ‘original sin’ and were considered to be without souls. If this was not enough they were thought to possess very little intelligence, be incapable of rational or logical thought and to be influenced by the moon. It comes as no surprise then, that women are more often than not, in her travels through history, placed into two categories, the virgin or a whore, but contrary to what we have lead to believe prostitutes were more widely accepted in medieval times and nuns were not always so saintly! In reality though, medieval women had far more to them, there are numerous examples of a determined women, such as Matilda, heir to the throne of England, Eleanor of Aquitaine, who went on crusade where she lead an army of ladies dressed in armour and Isabella of France who took up arms against the weak rule of her husband Edward II, scholars such as Felicie de Almania who spoke for the need of women doctors to treat women patients and who continued to practice medicine without a licence regardless of the threat of excommunication. Alice may have been born into a world of subservience, a world dominated by men, but this did not mean that she would have no say in how her life was run, far from it.

As a female child, Alice’s education would have been based on the service of others, and as a young woman she could have found herself being sent to another household to receive a basic education in the duties of a lady, or destined for a life within the wall of a convent. However, Alice was, as were many women of her status, destined for marriage and the advancement of her family.

Alice was probably the elder of the two Mohun daughters, born soon after the marriage of her parents and while she lay, fur wrapped in her cradle, she was betrothed to the heir of William Clinton, a west country feudal lord in the Country of Devon. No doubt a financial settlement had been arranged, for the Clinton's expected Alice to bring to the marriage, which took place between 1234 and 1237, her share of her family's inheritance. Her dowry may have been either money or goods and in return the Mohuns would expect an endowment of lands. This came in the form of the manor at Aston Clinton in Buckinghamshire, and Aston Chiverley, a sub-division of Aston Clinton, especially created for the couple for life. Alice’s marriage to William Clinton was an advantageous one, her father in law giving the couple lands to the considerable value of 40 shillings.

Pro filia Reginaldi de Moyun. Rex vicecomiti Buk, salutem. Alicie filie ipsius Reginaldi, et idem Willelmus de assensu et voluntate predicti Willelmi, patris sui, dotasset ipsam Aliciam uxorem suam de quadraginta libratis terre cum pertinentiis in Eston

(On behalf of the daughter of Reginald of Moyun, sheriff of Buckinghamshire to the king, greeting. Alice, daughter of the said Reginald, and the same William, with the consent and will of the said William, his father, the very Alice his wife, of the forty-worth of land with the appurtenances in Eston.)

As a female child, Alice’s education would have been based on the service of others, and as a young woman she could have found herself being sent to another household to receive a basic education in the duties of a lady, or destined for a life within the wall of a convent. However, Alice was, as were many women of her status, destined for marriage and the advancement of her family.

Alice was probably the elder of the two Mohun daughters, born soon after the marriage of her parents and while she lay, fur wrapped in her cradle, she was betrothed to the heir of William Clinton, a west country feudal lord in the Country of Devon. No doubt a financial settlement had been arranged, for the Clinton's expected Alice to bring to the marriage, which took place between 1234 and 1237, her share of her family's inheritance. Her dowry may have been either money or goods and in return the Mohuns would expect an endowment of lands. This came in the form of the manor at Aston Clinton in Buckinghamshire, and Aston Chiverley, a sub-division of Aston Clinton, especially created for the couple for life. Alice’s marriage to William Clinton was an advantageous one, her father in law giving the couple lands to the considerable value of 40 shillings.

Pro filia Reginaldi de Moyun. Rex vicecomiti Buk, salutem. Alicie filie ipsius Reginaldi, et idem Willelmus de assensu et voluntate predicti Willelmi, patris sui, dotasset ipsam Aliciam uxorem suam de quadraginta libratis terre cum pertinentiis in Eston

(On behalf of the daughter of Reginald of Moyun, sheriff of Buckinghamshire to the king, greeting. Alice, daughter of the said Reginald, and the same William, with the consent and will of the said William, his father, the very Alice his wife, of the forty-worth of land with the appurtenances in Eston.)

The Clinton family originated in France. After the conquest they acquired the manor of Glympton in Oxfordshire from which their name is derived. The manor was held by Geoffrey de Clinton, Henry I's chamberlain and William Clinton's great grandfather. By 1233 Glympton had passed, as part of the Brewer inheritance to Alice's grandmother and descended through the Mohun family line until 1253. The manor Aston Clinton was held by the Clinton family from 1193, it passed to the William Clinton who was a minor on the death of his father in 1216. By 1219 William had received his inheritance.

The tradition age of consent for marriage was fourteen, and Alice was probably just fifteen when her marriage to William Clinton took place. Accepting her lot, Alice would have gone into this marriage a frightened and bewildered little girl, with that in mind and her young age, physical relations may have been delayed for fear of the damage a pregnancy in one so young could do. This might well account for the fact that no children were born to Clinton, but it looks more likely that it was William Clinton demise in 1237 that was the real reason. Clinton’s death must have occurred between the 21st April 1237 when he is mentioned in the Fine Rolls of Henry III, as paying the king a fine of one mark and the 25th October 1237, when his estate is mentioned as being held by the crown. Following this, Alice was entitled, by law, to a third of their husband's property for her use during her widowhood, and at least a third of his goods such as jewelry and furniture. As a childless widow, Alice could control and live on her estates with her circumstances unaffected as long as she had a guarantor and an inventory of the estates belongings. Her guarantor probably would have been her father. Between the date of the above entries and the date of a Charter of the Soke of Mohun, in Westminster given by Reynold Mohun in 1245 Alice married for the second time.

In 1240, Aston Clinton passed to William's maternal aunt Nichith.

The king has taken the homage of Nichith’, who was the wife of William de Paris , for the lands that William de Clinton, nephew of the same Nichith’,

whose heir she is, held of the king in chief. Order to the sheriff of Buckinghamshire to take security for 10 m. for her relief.

By 1245, Alice had married, we know this from the Charter issued by Alice’s father confirming the Soke of Mohun to Alice and Robert Beauchamp. Witnessing this charter were Sir Roger de Turkeby, Henry III’s chief Councillor, Alice’s uncle William Mohun and James Audley. Audley, was the son of Henry Audley, of Heleigh in Staffordshire, who had received much of his lands in Staffordshire and Shropshire from Ranulf de Blondeville, Earl of Chester. Henry Audley was not a marcher lord himself but he did spend much of his time arbitrating between these English lords and the Welsh. James had come to prominence in 1250, doing much the same job as his father had in the Marches, and was important enough to accompany Richard Duke of Cornwall to his coronation as King of the Romas at Aachen. In 1258, his Welsh power base and his connections to the royal family saw him being appointed one of the royalist members of the council of fifteen appointed to advise Henry in accordance with the provisions of Oxford, a year later he witnessed, as James of Altithel, the king's confirmation of the council's powers on the 18th of October 1258.

In 1237, James Audley was in his late teens had not yet come to prominence and Alice was a young girl, just widowed. Between 1237 and 1244 the two began a sexual relationship and Alice was soon pregnant, their son James, was born before 1245. He was acknowledged by Audley and as he grew up took the surname of Audley. Whether a marriage between the two was considered is not known, but in 1244 James Audley married a woman further up the social ladder. Audley wife was Ela Longespree. Ela’s grandfather was William Longespree, an illegitimate son of Henry II and her grandmother was the Countess of Salisbury. By 1246 James was a wealthy baron, he received his inheritance to add to the lands that Ela brought to the marriage and was on the first rung of the ladder of social and political importance. Thelma W Lancaster, in her article on the Audleys of Heleigh Castle and Hulton Abbey suggests that the Longespree/Audley marriage was troubled one, but she gives no reason, she does suggest that Audley’s decision to give up their six year old son as a hostage to Simon de Montfort's forces in the August of 1264 may have been too much for Ela, and according to a court case (evidence of which I am unable to find) the couple were living apart.

A year after Audley’s marriage we can see from Soke of Mohun Charter, that Alice's second husband was Robert Beauchamp of Hatche in Somerset.

“Know that those present and to come that I Reynold de Mohun have given, granted and by the present my charter confirmed to Robert de Beauchamp (de Bello Campo) the younger with Alice my daughter in free marriage all my soke of Mohun, with all its appurtenances and liberties and with advowsons of churches with the city of London, and without between Fleet Bridge (pontem de Flete) and La Charringe, as I or any of my ancestors have at any time more fully, beter, or more freely, held the said soke; to hole and to have to him and his heirs issuing from the aforesaid Robert and Alice, freely, quietly, well and in peace, wholly, and hereditarily of me and my heirs for ever. I moreover Reynold de Mohun and my heirs and their heirs will warrant as aforesaid the aforesaid soke with all its appurtenances and its liberties within the city of London and without to the said Robert and Alice and their heirs issuing from them against all men and women, without any reservation. And that this my gift, grand and confirmation of the present my charter may remain valid (rata) and stable, I have put my seal to the present charter. Thes being witnesses:- Sir Roger de Turkeby, Sir James de Audeleg, Sir William de Mohun, Sir John B(r)etasch, Sir Nicholasle Lou (Lupo), Sir W. of Gyveltone, William son of Richard, citizen of London, Sir Philip of Couel, Sir Roger de la Doune, Sir Richrd Jocelyn, Sir Payn de Clermount, and others.”

The Beauchamp family were typical feudal lords, whose lands belonged, before the conquest to the family of Ivo who were military companions of the Saxon kings. Their descendant, Robert Beauchamp was tenant in chief who became lord of the manor of Hatch in Devon in 1252 on the death of his father.

The law gave husbands full rights to everything a woman owned, it would have been difficult for Alice to gain personal and legal freedom for she could not do or say what she wanted without his permission, Christine de Pisan, writing in the early part of the 15th century stated that a woman should ‘humble herself’ and ‘obey without complaint’. However, as previously mentioned there was a difference between what we think of the medieval woman and who she really was. Medieval women could be skilled administrators and fierce defenders of their property, and for all Alice’s ‘feminine weaknesses’ Beauchamp was not afraid to leave the running of his manor in her hands during his frequent absences. As the wife of a knight Alice would have been able to read, write and calculate probably far better than her husband, so while Robert Beauchamp was away supporting his king it would have been left to Alice to look after the finances of the manor. It if was a large one it could have had over a thousand acres and the house itself a great hall, kitchen, storerooms and servants quarters.

“Know that those present and to come that I Reynold de Mohun have given, granted and by the present my charter confirmed to Robert de Beauchamp (de Bello Campo) the younger with Alice my daughter in free marriage all my soke of Mohun, with all its appurtenances and liberties and with advowsons of churches with the city of London, and without between Fleet Bridge (pontem de Flete) and La Charringe, as I or any of my ancestors have at any time more fully, beter, or more freely, held the said soke; to hole and to have to him and his heirs issuing from the aforesaid Robert and Alice, freely, quietly, well and in peace, wholly, and hereditarily of me and my heirs for ever. I moreover Reynold de Mohun and my heirs and their heirs will warrant as aforesaid the aforesaid soke with all its appurtenances and its liberties within the city of London and without to the said Robert and Alice and their heirs issuing from them against all men and women, without any reservation. And that this my gift, grand and confirmation of the present my charter may remain valid (rata) and stable, I have put my seal to the present charter. Thes being witnesses:- Sir Roger de Turkeby, Sir James de Audeleg, Sir William de Mohun, Sir John B(r)etasch, Sir Nicholasle Lou (Lupo), Sir W. of Gyveltone, William son of Richard, citizen of London, Sir Philip of Couel, Sir Roger de la Doune, Sir Richrd Jocelyn, Sir Payn de Clermount, and others.”

The Beauchamp family were typical feudal lords, whose lands belonged, before the conquest to the family of Ivo who were military companions of the Saxon kings. Their descendant, Robert Beauchamp was tenant in chief who became lord of the manor of Hatch in Devon in 1252 on the death of his father.

The law gave husbands full rights to everything a woman owned, it would have been difficult for Alice to gain personal and legal freedom for she could not do or say what she wanted without his permission, Christine de Pisan, writing in the early part of the 15th century stated that a woman should ‘humble herself’ and ‘obey without complaint’. However, as previously mentioned there was a difference between what we think of the medieval woman and who she really was. Medieval women could be skilled administrators and fierce defenders of their property, and for all Alice’s ‘feminine weaknesses’ Beauchamp was not afraid to leave the running of his manor in her hands during his frequent absences. As the wife of a knight Alice would have been able to read, write and calculate probably far better than her husband, so while Robert Beauchamp was away supporting his king it would have been left to Alice to look after the finances of the manor. It if was a large one it could have had over a thousand acres and the house itself a great hall, kitchen, storerooms and servants quarters.

Robert Beauchamp spent much of his time battling against the Welsh alongside Henry III, it was in these Welsh wars that both Alice’s father and grandfather fought. By 1255, the civil war in England between Henry III and his barons had escalated, and by this time Alice had given birth to Beauchamp’s five children, Robert, John, Humphrey, Alice and Mary. We know that pregnancy and the birth was a risky business at this time. Just as in our world today, women like Alice would have been attended at the birth of her children, but these attendants knowledge was gained through experience rather than any training. Infant mortality was high and the death of the mother in childbirth was a common occurrence too, however, Alice managed to live through six pregnancies and births.

An undated writ names Robert as his father’s heir, but this writ is the last time we hear of him and in 1263 on the death of Beauchamp, John is named as heir so we have to assume that Robert had predeceased his father. John is stated as being born before 1249 and had married Cecily, daughter of William de Forz and Maud de Ferrers, he died in the October of 1283 holding Ottery Mohun under his uncle, William Mohun. Humphrey Mohun (my ancestor) was the youngest of Alice’s sons by Beauchamp, he had married Sybil Oliver, daughter of Walter Oliver of Wambrook in Devon and is stated as being his brother Johns heir, but it seems unlikely as John had two sons and two daughters. Of the Beauchamp daughter’s Mary and Alice I can find, as yet, nothing written.

Robert Beauchamp he had supported Henry III against Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in 1256 and he may supported the king during the Montfort rebellion, if he did there is no mention of it. It was in this unsettled period that Alice was widowed for the second time, Robert Beauchamp died in 1263, leaving behind at least four of his children under the age of fourteen, the children's ward ships, it has been said, were granted to James Audley. This fact may be true, but I have found no evidence to back it up, however the suggestion may come from the incorrect notion that Beauchamp’s eldest son and heir, John Beauchamp, had married Audley’s daughter Joan and that he had died during the last month of Joan’s pregnancy, (it was common practice for a ward to be married into the family of whom the ward ship had been granted.) John Beauchamp, had in fact, married Cicely de Vivonne and had died in 1283. Also linked to this wardship grant, is the idea that Alice was Audley’s mistress. The term mistress means

“a woman having an extramarital sexual relationship, especially with a married man.”

If we apply this to Alice, this would mean that she had continued her relationship with Audley even though they were both married or the relationship began again when his marriage to Ela was in trouble, if that was the case, any one of Beauchamp's children could have actually been Audley’s. The other possibility could be that she became his mistress, after the death of her husband and his marriage had failed, until his death in 1272. This assumption is backed up by Alice’s claim that Audley had granted her the land and rights of the manor of Horseheath in Cambridgeshire in 1263. Following Audleys death, she was forced to fight Audley's legitimate children's claim on the estate in court. It was not until 1278 that she finally received the lands, but on her son James’s death in 1286, it was lost and reverted to James Audley's youngest son Hugh, who land rights Ela Audley also fought tooth and nail to protect. This counter claim on Horseheath may have been the result of the Audley heir’s trying to claim back as much property as possible to gain revenue to pay back the many debts his father had left. It also, if we delve into the realms of romantic historical fiction, may have been Hugh Audley’s way of taking back, on behalf of his spurned mother, what they had had lost to James’s mistresses family. Whatever the real reason, by 1313, the manor of Horseheath had reverted back to Alice's grandson James and on his death to his sonWilliam Audley, whose memorial brass you can see below.

An undated writ names Robert as his father’s heir, but this writ is the last time we hear of him and in 1263 on the death of Beauchamp, John is named as heir so we have to assume that Robert had predeceased his father. John is stated as being born before 1249 and had married Cecily, daughter of William de Forz and Maud de Ferrers, he died in the October of 1283 holding Ottery Mohun under his uncle, William Mohun. Humphrey Mohun (my ancestor) was the youngest of Alice’s sons by Beauchamp, he had married Sybil Oliver, daughter of Walter Oliver of Wambrook in Devon and is stated as being his brother Johns heir, but it seems unlikely as John had two sons and two daughters. Of the Beauchamp daughter’s Mary and Alice I can find, as yet, nothing written.

Robert Beauchamp he had supported Henry III against Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in 1256 and he may supported the king during the Montfort rebellion, if he did there is no mention of it. It was in this unsettled period that Alice was widowed for the second time, Robert Beauchamp died in 1263, leaving behind at least four of his children under the age of fourteen, the children's ward ships, it has been said, were granted to James Audley. This fact may be true, but I have found no evidence to back it up, however the suggestion may come from the incorrect notion that Beauchamp’s eldest son and heir, John Beauchamp, had married Audley’s daughter Joan and that he had died during the last month of Joan’s pregnancy, (it was common practice for a ward to be married into the family of whom the ward ship had been granted.) John Beauchamp, had in fact, married Cicely de Vivonne and had died in 1283. Also linked to this wardship grant, is the idea that Alice was Audley’s mistress. The term mistress means

“a woman having an extramarital sexual relationship, especially with a married man.”

If we apply this to Alice, this would mean that she had continued her relationship with Audley even though they were both married or the relationship began again when his marriage to Ela was in trouble, if that was the case, any one of Beauchamp's children could have actually been Audley’s. The other possibility could be that she became his mistress, after the death of her husband and his marriage had failed, until his death in 1272. This assumption is backed up by Alice’s claim that Audley had granted her the land and rights of the manor of Horseheath in Cambridgeshire in 1263. Following Audleys death, she was forced to fight Audley's legitimate children's claim on the estate in court. It was not until 1278 that she finally received the lands, but on her son James’s death in 1286, it was lost and reverted to James Audley's youngest son Hugh, who land rights Ela Audley also fought tooth and nail to protect. This counter claim on Horseheath may have been the result of the Audley heir’s trying to claim back as much property as possible to gain revenue to pay back the many debts his father had left. It also, if we delve into the realms of romantic historical fiction, may have been Hugh Audley’s way of taking back, on behalf of his spurned mother, what they had had lost to James’s mistresses family. Whatever the real reason, by 1313, the manor of Horseheath had reverted back to Alice's grandson James and on his death to his sonWilliam Audley, whose memorial brass you can see below.

By 1268, Alice was nearing her fiftieth birthday, and that year John Beauchamp received his father's estates and continued the Beauchamp family line at Hatch. Alice could have lived at either of her manors, but she most probably lived at the manor house Horseheath, if we believe that her relationship with James Audley continued right up to his death. Horseheath and Aston Chiverley were held by Alice and then passed, on her death, to her son by James Audley. Both properties remained in the hands of Alice’s Audley descendents until they passed by marriage to one John Rose during the reign of Richard II.

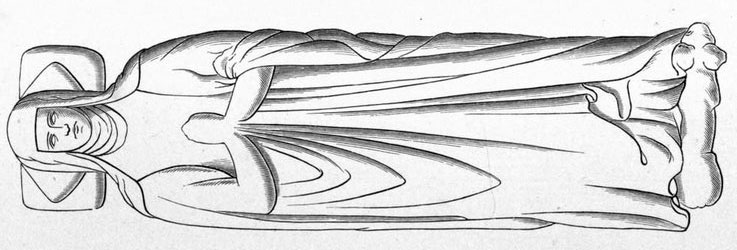

So, contrary to what we have been forced to believe, medieval women were effective administrators and fierce defenders of their property, doing whatever was necessary to protect the rights of their offspring. In the case of Alice as James Audley’s mistress and Ela as his wife, we can see both women doing just that. Alice lived another twenty years following her husband's death, and ten years following the death of James Audley, but of her life in those years there is no record. In death however, we get to see what Alice may have looked like, or at least a representation of a woman of her time.

There is an effigy in the Church of St Mary the Virgin in Axminster that dates to between 1228 and 1275, this is thought to be of Alice Mohun. At this time female figures such as this who are depicted holding books, shrines, or a shields were often foundresses or and heiresses. Alice’s mother, with her husband Reynold Mohun founded the nearby Newenham Abbey.

Therefore it is highly likely that the effigy below is of Alice’s mother and not Alice.

However, lying in the nave of the Church of St John the Baptist, in the village of Membury in Devon is a recumbent stone effigy underneath the north window of the north transept. This female is wearing a long gown, a veil and wimple that has been dated to the later part of the thirteenth century. This effigy is also thought to be Alice Mohun. Her hands are together in prayer, but as you can see there is nothing between them. Can we take from this that she is Alice Mohun, my 22nd great grandmother, the wife of Robert Beauchamp and lover of James Audley?

I would like to think so.

I would like to think so.

Alice Mohun’s death in 1282, ended my branch of the Mohun family.

The Mohun families main branch survived unto middle of the fourteenth century when the last male Mohun died childless and his wife Joan was left in control of the estate. Eventually, the Mohun’s mighty castle at Dunster passed into the hands of Elizabeth Luttrell whose descendants held thecastle and manor for the next 600 years.

Of course, family history is more than a name, it is a blood line and the Mohun blood is mixed with many families throughout the centuries. Alice’s bloodline continues through the Beauchamp family of Hatch Beauchamp, their story is told through their own family history.

The Beauchamp family history is work in progress.

The Mohun families main branch survived unto middle of the fourteenth century when the last male Mohun died childless and his wife Joan was left in control of the estate. Eventually, the Mohun’s mighty castle at Dunster passed into the hands of Elizabeth Luttrell whose descendants held thecastle and manor for the next 600 years.

Of course, family history is more than a name, it is a blood line and the Mohun blood is mixed with many families throughout the centuries. Alice’s bloodline continues through the Beauchamp family of Hatch Beauchamp, their story is told through their own family history.

The Beauchamp family history is work in progress.