c 1698 Peter Lakeman 1740

A New Beginning

A New Beginning

The origins of the surname of Lakeman can be traced to the language of the Anglo-Saxons who used the word ‘Lacu’ in reference to a lake or to a time following the Norman Conquests when lake was spelt as it is today. With the suffix of ‘man’ it is not too difficult to work out that my distant ancestors were dwellers who lived by a large expanse of water. According to the 1841 census there were 303 people with the Lakeman surname living in the whole of the country, in 1881 there were 431, and by 2016 only 333 people were going by this surname. Families who have locative surnames like the Lakeman’s and occupational surnames should, in theory, appear in all parts of the country each having their own ‘Adam and Eve’ and therefore are not of the same family. I wonder though, with such a small number is it possible that the Lakeman's spring from one family who lived on the banks of a lake somewhere in England?

One of the earliest references to the Lakeman surname appears in 1320 in records of Hornchurch Priory in Essex and just over twenty years later a Philip Lakeman can be found in the Subsidy Rolls of Broad Clyst in Devon. That same year a John Lakeman appears in another Devon Subsidy Roll, this time in Ermington, another Devon village. In 1573, in the reign of Elizabeth I there is a Joha and a William Lakeman appearing in Ugborough, the aforementioned Ermington's neighbouring village.

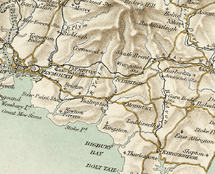

Ugborough with it’s monthly sheep and cattle market and the farming community of Thurlestone has the largest amount of Lakeman's registered as being born before the turn of the 17th century and it is at this time that Peter Lakeman was born, we don’t know his parents or if he had any siblings. I have found no proof of where he came from, but putting together the fact that there are no records of his birth, baptism or marriage in Cornwall with the demography of Devon, it seems, this county is the only place could have come from and his ancestors originated.

One of the earliest references to the Lakeman surname appears in 1320 in records of Hornchurch Priory in Essex and just over twenty years later a Philip Lakeman can be found in the Subsidy Rolls of Broad Clyst in Devon. That same year a John Lakeman appears in another Devon Subsidy Roll, this time in Ermington, another Devon village. In 1573, in the reign of Elizabeth I there is a Joha and a William Lakeman appearing in Ugborough, the aforementioned Ermington's neighbouring village.

Ugborough with it’s monthly sheep and cattle market and the farming community of Thurlestone has the largest amount of Lakeman's registered as being born before the turn of the 17th century and it is at this time that Peter Lakeman was born, we don’t know his parents or if he had any siblings. I have found no proof of where he came from, but putting together the fact that there are no records of his birth, baptism or marriage in Cornwall with the demography of Devon, it seems, this county is the only place could have come from and his ancestors originated.

One of the few facts that are known about Peter is that he was trained in the art of tailoring, as there is no mention of Peter in records held by the Merchant Taylors' Company it is highly likely that he was born into a family who had it links with either the farming community or the wool industry. Therefore it has to be assumed that he was a rural tailor who may have been apprenticed with a family member or a local tailor.

Devon was an important area in the manufacture of woolen cloth, the two most common fabrics woven at this time was kersey and serge. Kersey was made from lower grade wool and the cloth made from it was coarse, it was used to make garments such as military uniforms. Serge was a finer cloth that in time would be used in the making of the suit that is a waistcoat and jacket that was popularised during the reign of Charles II who is credited with the suit's ‘invention.’ Charles I had favoured doublets with full sleeves and full breeches, Charles II went for short doublets and petticoat breeches and gradually moved to a coat, waistcoat and breeches. By the beginning of the 18th century this style of suit was made up of three parts - a fitted knee-length coat, a jacket and breeches, such as the one in the image below, made up of expensive fabrics such as silks, velvet's, and brocades.

This style of jacket can be dated to c1723 when we know Peter Lakeman was a qualified tailor.

Devon was an important area in the manufacture of woolen cloth, the two most common fabrics woven at this time was kersey and serge. Kersey was made from lower grade wool and the cloth made from it was coarse, it was used to make garments such as military uniforms. Serge was a finer cloth that in time would be used in the making of the suit that is a waistcoat and jacket that was popularised during the reign of Charles II who is credited with the suit's ‘invention.’ Charles I had favoured doublets with full sleeves and full breeches, Charles II went for short doublets and petticoat breeches and gradually moved to a coat, waistcoat and breeches. By the beginning of the 18th century this style of suit was made up of three parts - a fitted knee-length coat, a jacket and breeches, such as the one in the image below, made up of expensive fabrics such as silks, velvet's, and brocades.

This style of jacket can be dated to c1723 when we know Peter Lakeman was a qualified tailor.

With his apprenticeship served Peter would have had to find employment, it seems that he spent the first five or six years of being ‘qualified’ in Devon, however by end of 1718 Peter had married and had a baby son, his wife Sibella was just pregnant with their second child. For reasons unknown Peter made the decision to leave the county of his birth and look for work in pastures new. The aforementioned villages of Ugborough and Emington lie just over six miles north of Thurlestone, a small village that sits on the south coast of Devon. The stretch of coastline between Thurlestone and the Cornish fishing village of Mevagissey measures just under fifty miles and just over thirty as the crow flies. The closeness of the West Country fishing communities meant that there would have been frequent migration between Devon and Cornwall’s coastal villages, the movement in the population wasn’t just limited to west coast of Cornwall, when the Lakemans moved the population of Cornwall had risen by more than a quarter. What ever it was, something or someone enticed Peter Lakeman to move to Mevagissey, sadly the reasons for it will forever be lost to history.

When the Lakeman family arrived in Cornwall the county was as remote as it was in the middle ages, it was still was a county apart.There were few roads that were suitable for carts so the majority of the populace rarely traveled away from their place of birth so they pursued their old way of life, they spoke their own distinctive language, celebrated their festivals and listening to the stories of Cornish giants and piskies. The population of Mevagissey was isolated from the rest of Cornwall because the construction of roadways were limited by the landscape. To enter the county by road travelers would have had to cross the River Tamar and then make their way across Bodmin Moor, a beautiful but often treacherous area of land where the lanes and tracks were narrow and steep, they were slippery and dark in the winter and overgrown and tree lined in the summer. Travel by road into into Cornwall was done by packhorse, their drivers would have to steer their carts through high banked, twisting tracks using pack horse bridges to cross the small rivers and streams, their passengers would have had to stop off at inns overnight. It was a journey to Mevagissey from Devon, I think, the Lakemans didn’t make. Travelling to Mevagissey by boat, on the other hand, would be a quick and easy journey.

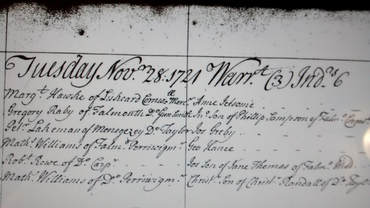

Before Peter and Sibella left the shores of Devon Sibella had given birth to a daughter they had named Mary, there is no references to either their son John or Mary’s baptism in Cornwall, so it is likely that both children were born in Devon and it was as a family of four that they arrived in Mevagissey in the year 1719. Whoever welcomed them on their arrival, where they lived or how Peter started in business goes unrecorded. However what is known is that by the August of 1721 Peter Lakeman had managed to set himself up in business. It would seem that Peter was able to begin work almost straight away which makes me think that he was not a ‘stranger’ but already had some connection within the village, however who that was is not known. In the February of that year Sibella was again pregnant and by the August it would seem that Peter was doing well enough for him to employ an apprentice who went by the name of Joseph Greby. Evidence for this can be found in the Register of Duties Paid for Apprentices’ Indentures.

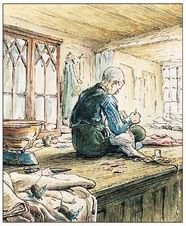

This register is an official record of apprentices, it recorded the stamp duty that was payable on the indenture (a legal document were a master agreed to instruct an apprentice in his trade for an agreed number of years) of the apprenticeship. It is really difficult to know exactly what services Peter Lakeman performed as a tailor in Mevagissey, it would be nice to think that he made jackets and waistcoats for the local gentry such as Colonel Lewis Tremayne of Heligan, who was Mevagissey’s wealthiest landowner. The Heligan estate is situated in the hills above the village. Maybe Peter worked on coats such as the ones worn by Winston Graham’s characters in his Poldark series, in reality though most of his customers were not that grand. It is highly unlikely that Peter had a shop, it is probable that he worked out of his home sitting cross legged on his workbench in front of a window replacing buttons, repairing tears or making old cloth into new ones. I have not been able to find out exactly where the family lived but it could have been in any of the houses that ran along the labyrinth of paths and alleys that snake their way up and down the hillside or maybe he was lucky enough to look out across Mevagissey Bay.

Mevagissey has always had some sort of protection from the elements, be it natural, like the jagged cliffs or its medieval harbour wall that can still be found situated on Island Quay. There was no boat yard and only a few fishing boats would bring in their catch of Pilchards as the tide permitted. Mevagissey was small busy fishing port and when the Lakeman's arrived at the beginning of the 18th century the growth in trade within the fishing industry had not yet begun, however it seems that there was enough trade to generate an income to support his growing family. As the years passed, Peter would have been well aware that Mevagissey was changing from a fishing village into a small port, testament to this the Mevagissey token.

Tokens such as these were issued between in the late 17th century as a response to a lack of currency being produced by the crown. To help the situation, traders began producing tokens to be used locally such as the one in the above image that was issued by fish merchant John Keagle. These tokens were accepted by other traders in the local area, it was a system that relied on trust. By 1774 increased trade in Mevagissey meant that new wharves and jetties were being constructed and a new harbour was built to accommodate the larger ships. New storage facilities were also built to store their cargo. Peter would not live to reap the benefits from the great change, however they did have the honour of being the first Lakeman's to live in Cornwall.

John and Mary, the first two Lakeman children were followed by a second son who was named Peter, he was the first Lakeman whose name appears in any of St Peter's church registers. He was baptised in the October of 1721. Peter was soon followed by a third son named William whose baptism is recorded as taking place on the 13th February in 1723. This happy occasion was marred just two months later by the death of five year old Mary whose burial is recorded as the 12th April 1724. Three months later Sibella was pregnant and in the August of 1725 she gave birth to their fourth son who they named Ambrose. Ambrose only survived six months, his burial is recorded in St Peter’s burial register as the 13th of March 1725.

You may look at the dates of Ambrose’s birth and burial and think that I have made a mistake with the dates, however the fact is that in England, prior to 1752, the new year began on the 25th March, the dates being governed by the Gregorian calendar. In 1752 the Julian calendar was implemented and New Years Day was celebrated on January Ist - this is how it appears that Ambrose burial occurred before he was born.

Peter had lost two of his children in two years, his thoughts and feelings on the matter go unrecorded, however Sibella was soon pregnant again. In the February of 1726 Peter and Sibella’s fifth son, who they named William, was born. The Lakeman's, like many people of this time, followed tradition and named their new baby as that of their dead child. When their next child was discovered to be a daughter they named her Mary, her name was added to Mevagissey’s baptism register in the March of 1728. Two years later, in 1730, tragedy struck the family again when six year old William died and was laid to rest alongside his four siblings on the 10th September. Two months after the death of William, Sibella was again pregnant, this third daughter they named Catherine, she was born in the May of 1737, her birth was followed by a son born in 1734 and who was once again given the name of William. William was followed by two more children, Ann, my ancestor, was born in the October of 1736. The last four children would grow into adulthood, and in a time of high infant mortality, you could argue that they were, in fact, quite lucky.

You may look at the dates of Ambrose’s birth and burial and think that I have made a mistake with the dates, however the fact is that in England, prior to 1752, the new year began on the 25th March, the dates being governed by the Gregorian calendar. In 1752 the Julian calendar was implemented and New Years Day was celebrated on January Ist - this is how it appears that Ambrose burial occurred before he was born.

Peter had lost two of his children in two years, his thoughts and feelings on the matter go unrecorded, however Sibella was soon pregnant again. In the February of 1726 Peter and Sibella’s fifth son, who they named William, was born. The Lakeman's, like many people of this time, followed tradition and named their new baby as that of their dead child. When their next child was discovered to be a daughter they named her Mary, her name was added to Mevagissey’s baptism register in the March of 1728. Two years later, in 1730, tragedy struck the family again when six year old William died and was laid to rest alongside his four siblings on the 10th September. Two months after the death of William, Sibella was again pregnant, this third daughter they named Catherine, she was born in the May of 1737, her birth was followed by a son born in 1734 and who was once again given the name of William. William was followed by two more children, Ann, my ancestor, was born in the October of 1736. The last four children would grow into adulthood, and in a time of high infant mortality, you could argue that they were, in fact, quite lucky.

By 1737, Sibella may well have been in her late thirties or early forties but she was still within her child bearing years. At the rate Sibella gave birth I doubt if family planning ever crossed their minds therefore it was highly likely that Sibella would be pregnant again within six months it was therefore essential that Peter continues to work hard. Record’s suggest that Peter’s business was successful and had grown enough for him to open a shop, but they do not tell us the good he was selling. He may well have still been in the business of tailoring but these records suggest that he may have subsidised his business by selling tobacco.

Napoleon called the British a nation of shopkeepers and he was right, by the middle of the 17th century there were up to 40,000 shopkeepers in England and Wales and records dated to 1737, and as just mentioned, Peter Lakeman was one of them. By this time the aforementioned Joseph Greby would have worked through his apprenticeship, there is no mention of him at all after 1721 therefore it is likely that he left to pursue work elsewhere. Peter’s eldest sons John and Peter were twenty and eighteen respectively, but it is not known if they worked with their father. If Peter was still a tailor then he would probably not have stocked fabrics, neither would he stock the outer portions of a garment such as the lining, buckram for the interfacing, buttons and thread, the purchasing of these items were left to the customer who would bring the fabric into a tailors shop so that the garment could be made up. A full three piece suit, made up in a cheaper fabric would cost about 24 shillings, the cost of repairing garments or remaking them into something new would be much cheaper of course. The customer could expect to return in about two weeks to collect his finished garment and settle his bill, however by the early summer of 1737 the subject of money began to cause Peter Lakeman grief. So, why was his business in trouble?

The answer may lie in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars. By the end of these wars there was no call for the manufacture of woolen uniforms and English goods were, on the whole, of poor quality and were much inferior to that of France, Germany and Italy, imported fabric and a drop in the market was not good for the English textile trade or the small local tailor. However, England would go on to manufacture goods to match the standard of Europe by using wool, cotton and ribbons that were manufactured in the Midlands, for the small Cornish trader in textiles what the Industrial Revolution gave out with one hand, it took with another.

The answer may lie in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars. By the end of these wars there was no call for the manufacture of woolen uniforms and English goods were, on the whole, of poor quality and were much inferior to that of France, Germany and Italy, imported fabric and a drop in the market was not good for the English textile trade or the small local tailor. However, England would go on to manufacture goods to match the standard of Europe by using wool, cotton and ribbons that were manufactured in the Midlands, for the small Cornish trader in textiles what the Industrial Revolution gave out with one hand, it took with another.

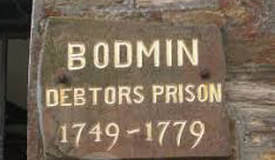

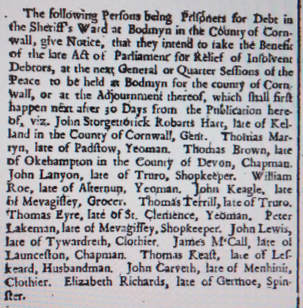

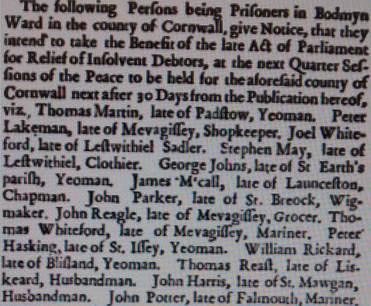

Regardless of this, Peter did encounter financial difficulties and whether the cause was a change in the market, poor management or extravagance, the end result is the same, he found himself in Bodmin Debtors prison in the June of 1737. It is not, as yet,* known how much Peter owed or who he owed money too, however there is no record of him being declared bankrupt, what Peter was was an insolvent debtor, this meant that he owed his creditors less than £100 and for this he could be imprisoned indefinitely until the debt was repaid.

Peter was sent to prison in Bodmin, a large market town that lies just over thirteen miles to the north of Mevagissey, its debtors prison could be found at the bottom of Prison Lane, what is now Crockwell Street. The ethos of the debtor prison was to confine, not to punish, no doubt the prisoners felt differently though. Debtors, like Peter, were usually housed separately away from the rest of the prison inmates and the way they lived and were treated was dependent on what their family or friends could afford to pay. However, conditions varied from prison to prison but more often than not were operated for profit, and wardens were known to be cruel. In other debtors prisons, such as The Fleet in London, conditions were appalling, sometimes whole families were cramped into overcrowded, cold, damp cells. Marshalsea, was another London debtors prison, this was equally horrendous - John Dickens, the father of author Charles Dickens was incarcerated there in the February of 1824, when Charles was just 12 years old. He was so affected by his father's experiences in debtors prison that he would go onto write his book Little Dorrit on the subject.

There are no family stories of Peter’s time in prison, but we can imagine it was a dreadful and frightening experience. Within a few weeks of his imprisonment Peter applied to the courts for Debtors Relief siting the 1729/35 Act of Parliament for Relief of Insolvent Debtors.

There are no family stories of Peter’s time in prison, but we can imagine it was a dreadful and frightening experience. Within a few weeks of his imprisonment Peter applied to the courts for Debtors Relief siting the 1729/35 Act of Parliament for Relief of Insolvent Debtors.

Debtors like Peter published notices in the London Gazette and in local newspapers, this was done in order to alert creditors and Peter’s notice was published in the Gazette on the 25th June 1737 and again on the 2nd August with the intention of having his case brought before the Justice of the Peace at the next Quarter Session. Quarter Sessions were, as it states, held every quarter. The first being at Epiphany - January, followed by Easter - March/April, Midsummer June/July and Michaelmas - September/October. It's a bit of a puzzle why Peter’s name appears in two separate publications of the London Gazette when his hearing for both would take place in the Michaelmas session. One answer could be that he settled his debt in the June but defaulted and returned to prison reapplying for debtors relief that fell within the same period. Whatever the reason Peter spent an unknown* amount of time in Bodmin Debtors prison before his application for relief and another three months from the date of the first publication of his intentions to the sitting of the September court. During that time Sibella was left alone to care for their small children. Finally, at his court appearance the justices who heard Peter Lakeman's case were satisfied that he would repay his debt and he was finally discharged, this also meant the person or persons Peter owed money to could proceed in collecting his debt.

Hopefully, Peter Lakeman returned to business a wiser man and no doubt thankful that he had the chance to celebrate the Christmas of 1737 with Sibella and his children as a free one.

Hopefully, Peter Lakeman returned to business a wiser man and no doubt thankful that he had the chance to celebrate the Christmas of 1737 with Sibella and his children as a free one.

As mentioned previously, the new year began in the March, by which time the family had celebrated the marriage of their eldest son John to Margaret Robyns and before the year was out Margaret was pregnant with their first child, Sibella too became pregnant with her eleventh child. The following November, their daughter in law gave birth to a boy they named John and the month before Sibella had given birth to her last child, a son she named Thomas who was baptised on the 2nd October 1738. Two years later, in the September of 1740, Peter and Sibella became grandparents for the second time to John and Margaret’s son Francis, but sadly neither of them would live long enough to see the child pass into its second month, by the first week of November both Peter and Sibella were dead. The their cause of death is not known, however there is some evidence that might point to one reason.

The long hard winter of the previous year was followed by a dry spring and hot summer which lead to a epidemic that it was said to be akin to dysentery. In the autumn it had arrived in both at Plymouth and Bristol, carried into the ports by merchant ships. By the summer of 1741 it had spread north and was described as being ‘lost in a fever of the bilious kind.’ A study of St Peter's Church burial registers for 1740 show us that this epidemic had made its way south pretty quickly. Comparing the number of deaths in the years either side of 1740 I found that they were treble that of the four previous years and double that of the following two. Sixty-six people died in Mevagissey in 1740 compared to 24 in 1739 and 34 in 1741- poor Peter and Sibella were two of the sixty-six. The burial of Peter and Sibella’s mortal remains took place the 17th November 1740. It is unlikely that they both died on the same day, chances are that they were both very sick and died within days of each other and the decision was made to bury them in the same grave at the same time.

Why I wonder did none of the Lakeman children succumb to this awful illness? Ann and Thomas would have been especially vulnerable due to their young age, the question that should be asked then is can their deaths be attributed to something else other than an infectious disease?

The long hard winter of the previous year was followed by a dry spring and hot summer which lead to a epidemic that it was said to be akin to dysentery. In the autumn it had arrived in both at Plymouth and Bristol, carried into the ports by merchant ships. By the summer of 1741 it had spread north and was described as being ‘lost in a fever of the bilious kind.’ A study of St Peter's Church burial registers for 1740 show us that this epidemic had made its way south pretty quickly. Comparing the number of deaths in the years either side of 1740 I found that they were treble that of the four previous years and double that of the following two. Sixty-six people died in Mevagissey in 1740 compared to 24 in 1739 and 34 in 1741- poor Peter and Sibella were two of the sixty-six. The burial of Peter and Sibella’s mortal remains took place the 17th November 1740. It is unlikely that they both died on the same day, chances are that they were both very sick and died within days of each other and the decision was made to bury them in the same grave at the same time.

Why I wonder did none of the Lakeman children succumb to this awful illness? Ann and Thomas would have been especially vulnerable due to their young age, the question that should be asked then is can their deaths be attributed to something else other than an infectious disease?

Peter and Sibella Lakeman had arrived in Mevagissey from Devon just twenty years earlier in the hope of starting a family and a new life and in this they were successful, fate however, chose to make their stay a little shorter than they expected. Peter, as I mentioned, was the first of his name to establish a family in Cornwall, a family whose name you can still find listed in any telephone directory or on the electoral register in Mevagissey to this day.

In 1740 Peter Lakeman left two grown up sons, John and Peter and five young children, Mary aged twelve, Catherine aged nine, William aged six, my ancestor Ann aged four and Thomas aged just two. All would live into adulthood, marry and have children of their own, the story of their lives will appear in another chapter.

*NB At the time of writing the Cornish Records Office in the midst of a move and therefore I have been unable to access Peter Lakemans prison records and burial records.

In 1740 Peter Lakeman left two grown up sons, John and Peter and five young children, Mary aged twelve, Catherine aged nine, William aged six, my ancestor Ann aged four and Thomas aged just two. All would live into adulthood, marry and have children of their own, the story of their lives will appear in another chapter.

*NB At the time of writing the Cornish Records Office in the midst of a move and therefore I have been unable to access Peter Lakemans prison records and burial records.