Introduction

The Lakeman’s have lived in Mevagissey since the beginning of the 17th century and their story begins when Mevagissey’s quay was not peopled with holidaymakers and when there were no houses to be found perched high on the steep slopes of Polkirt Hill. Mevagissey was, as H A Behenna writes in his book A Cornish Harbour, a vision in black and white devoid of colour and inhabited by just a few families that he calls the Lost Tribe. These people were descended from the original families who fished in the Atlantic Ocean centuries before and who lived in houses on the streets above the harbour where it is said a “Cornishman likes to live where he could toss a biscuit into the sea from his window.” The peaceful existence of this old community would eventually be overrun by the aforementioned tourist in what Behenna quite aptly calls the Kodak Age - a time of colour and the time of the photograph.

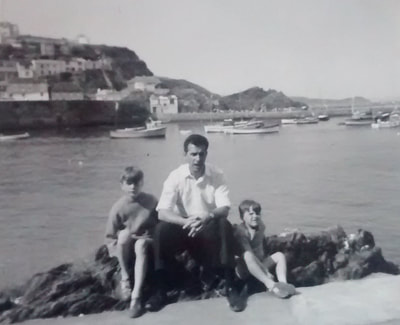

These photographs of my family and I were taken in Mevagissey in 1968, one hundred and seventeen years after my branch of the Lakemans left the village to set themselves up in Newquay, another small fishing village on the western shores of Cornwall. Newquay was where I was born and it was here on one of my grandfather’s cousin's fishing boats, that as a little girl, I went on a fishing trip. I remember we talked of how dangerous the sea can be, that day there was not a ripple between the harbour and the horizon, however other times I have seen waves so big they engulfed the whole of the harbour walls. It was the numerous tales of my ancestors life on the sea that first got me interested in genealogy, the story of my great-grandfather and his time in the Merchant Navy and of my great-great-grandfathers adventures all over the world as a sea captain - you see half of my ancestors were employed in jobs that involved with the ocean, they were fisherman, dock workers, ship captains, harbour masters and coast guards, the list goes on.

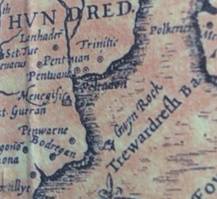

Today Mevagissey is a pretty fishing village that lies on the east coast of Cornwall, it nestles in a bay that lies between Black Head, the site of an Iron Age fort and Chapel Point a dangerous and exposed spot that separates Mevagissey bay from the neighbouring St Austell Bay. In ancient times, however, there was no such village only two small communities known as Lamoreck and Porthilly. The early inhabitants of these two settlements may have looked to St Meva and St Issey for their spiritual needs. St Issey, also known as Ysa, was a daughter of the Welsh king Brychan who was said to have befriended St. Meva and together they established a church, this small building would have been on this site from about the year 900. Lamoreck, in all likelihood, is the site of present-day Mevagissey and is mentioned twice in historical documents. It is mentioned first in the registers of Walter Branscombe, Bishop of Exeter who is stated as visiting this village (staying on the nearby Bodrugan estate) in 1258, it is mentioned again in 1302 in a fleet of fines as being the property of Adam of Lamoreck. Porthilly, the second settlement had established itself on the north side of the bay can be found along with a list of church incumbents in 1330. It is mentioned some two hundred years later in 1506 in a Writ of Dower where Margaret Nanfan, the widow of Richard Nanfan, administrator and court official during the reign of Henry VII, was granted Porthilly as part of the lands of her late husband’s estate. Lamoreck and Porthilly, the merging of these two communities in name occurred in the 15th century for there is a reference to Menagye-zey in Cardinal Wolsey’s inquisition of 1521 when he was looking into the rateable value of Cornish Churches and it can be seen quite plainly on English cartographer John Speeds map of 1610 written as Mevegifife.

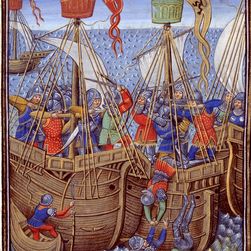

Evidence that the inhabitants of both villages were working together for a common cause can be found in a time when England was at risk of attack by both Spain and France. In 1442, Lemoreck and Porthilly supplied over 70 tons of fish to the English navy following an Act of Parliament that ordered Cornish fishing communities to supply fish to help guard the Channel against an attack. This is likely to have been initiated by French attacks on Gascony following a failed alliance between the English and the Armagnacs. From this point it is easy to see how fish caught in small Cornish fishing villages was being noticed for the revenue it could bring in and its importance to England's economy.

Fish, especially the Pilchard, that was caught at both Lamoreck and Porthilly, tied these two communities to the sea for generations, John Nordon, the 16th century topographer wrote of that the inhabitants of fishing villages took “great store” of the “manie kinds of verie excellent fish” and in 1591 Thomas Cely, Elizabeth I’s Yeomen of the Guard and probably also one of her spy’s informed Lord Burgley, the Lord Treasurer that “great preparations were being made for conveying away pilchards” Three years later 1594 an Act of Parliament was passed that stated that “no stranger should transport away any pilchers or other fish in cask unless such persons should previously have brought in a proportionate amount of clapboard fit for cast or else of cask.” Despite the great monetary benefits it brought the county, it seems that fish, according to antiquarian Richard Carew, came third in order of importance after farming and mining. However, Carew did write that the Pilchard was “least in bigness, greatest for gain and most in number.” The pilchard, it seems had become the darling of the Cornish fishing industry and resulted in fishing villages like Polkerris, Gorran Haven and Fowey holding the monopoly on this catch.

It was into this growing fishing community that Peter Lakeman, along with his wife and baby son John arrived in 1720.

It was into this growing fishing community that Peter Lakeman, along with his wife and baby son John arrived in 1720.

All works © Meandering Through Time