|

Elizabeth Hendley

1519 - 1596 |

Elizabeth Hendley was born in 1519, a year of important births and changes within society. Husband and wife, Henry II of France and Catherine de Medici were both born that year. In England, it was the year of the birth of Catherine Willoughby, the fourth wife of Charles Brandon, Henry Fitzroy, the illegitimate son of Henry VIII by Elizabeth Blount, and it is thought it was the year of the birth of Catherine Howard. Also this year, concerns were raised about the succession following the stillbirth of Catherine of Aragon and Henry’s daughter the year before - concerns were voiced that there may not be a legitimate male heir. However, it was not until a few years later that Henry began to become impatient with Catherine's inability to give him the son he so desired, and at the same time he became enamoured with Anne Boleyn. Also that year there were concerns about Yorkist claimants to the throne, Richard de la Pole, the son of John de la Pole, was still considered to be a threat to the Tudor dynasty.

Elizabeth was the eldest daughter of Walter Hendley and his first wife Elizabeth Ashburnham. She was born at Guestling in Sussex, the ancestral home of her mother Ellen Ashburnham, whose father, Thomas Ashburnham had been a local government official in the ports of Winchelsea and Rye. It was under Thomas's guidance that Elizabeth’s father pursued a career in law. Following the birth of Elizabeth’s younger sister Anne, their grandfather had arrived back in Guestling from London infected with the plague from which he soon died. Her mother also died that year, although she may well have died from complications in childbirth after giving birth to Anne, however her dying from the plague cannot be ruled out. Elizabeth was just four when this double tragedy occurred and her father left a widower with three young daughters. However, within four years he had married Margery Pigott, the nineteen year old widow of Thomas Cotton.

With both her maternal grandparents now dead, the family estate at Guestling passed to her cousin John Ashburnham and sadly, history doesn't tell us what exactly happened to the house at that time. Walter had made the decision to move his family back to his home of Coursehorn in Kent. Elizabeth’s paternal grandparents were still alive but Walter would have known that he would one day receive Coursehorn as his inheritance, and with this in mind the family moved into their own house on the manor where Margery could raise the children while Walter began his new career in London.

The exact date that Walter returned to Coursehorne is not known, it may have been before the death of his father in 1532, and if this was the case Elizabeth and her sisters would have had time to get to know their grandparents and it may be that they had a say in their upbringing. Gervais Hendley had family ties with three of the most wealthy families in the area, the Roberts (Walter Roberts was Elizabeth’s maternal great grandfather) the Bakers and the Culpepper’s, all four had business ties with local cloth making families too. While her father was in London he would have been confident in the knowledge that his children had a secure upbringing, and it was during the following few years that Walter made plans for their marriages. All three of Walter's daughters were married into families that the Hendley’s had known for years. Ellen, Walter’s second daughter, would marry Thomas Culpeper of Goudhurst and Anne, Walter’s youngest daughter, who was just a tiny baby when her mother died in 1523, would marry Richard Covert of Slaugham.

Elizabeth married into the family of Waller whose roots can be found embedded in the Midlands in the 11th century and who had acquired Lamberhurst, a manor just a few miles west of the Hendley’s own manor of Coursehorn sometime in the 12th century. In 1400 the family purchased Groombridge from William de Clinton, 4th Baron Say, they would own this estate for the next two hundred years.

The present house, Groombridge Place, seen below, stands on the site of the house that the Wallers would have lived in, but the moat most certainly would have been there at the time Elizabeth married William Waller. Moated sites are generally seen as the prestigious residences, they were not only a mark of high status but also

served to deter raiders and wild animals. Groombridge's moat first appears in historical record as a manor in 1286.

Elizabeth married into the family of Waller whose roots can be found embedded in the Midlands in the 11th century and who had acquired Lamberhurst, a manor just a few miles west of the Hendley’s own manor of Coursehorn sometime in the 12th century. In 1400 the family purchased Groombridge from William de Clinton, 4th Baron Say, they would own this estate for the next two hundred years.

The present house, Groombridge Place, seen below, stands on the site of the house that the Wallers would have lived in, but the moat most certainly would have been there at the time Elizabeth married William Waller. Moated sites are generally seen as the prestigious residences, they were not only a mark of high status but also

served to deter raiders and wild animals. Groombridge's moat first appears in historical record as a manor in 1286.

Most of the families living in the area around the Hendley’s manor at Coursehorn were connected via their interests in both the cloth and iron industry. However, the Hendley's had little to do with the iron industry and the Waller’s, it would seem, had no connection to the cloth industry. A marriage between the two families would make for a successful and profitable alliance, love at this time had very little to do with it! Unlike the Culpepper's, her sister’s husband's family, the Wallers, during the time of the Wars of the Roses and the rise of the Tudor dynasty seemed to have kept their heads down, their only claims to fame was during the Hundred Years War when Richard Waller was knighted by King Henry V on the Agincourt battlefield for the capture Charles, the Duke of Orleans. Some centuries later, William, and his cousin Hardress Waller fought on the Parliamentarian side against the king. Maybe Richard Waller’s famous success at Agincourt was the reason the Wallers were successful at Groombridge, it gave them prestige but not necessarily wealth (a ransom was never paid for the duke’s release) The Waller’s wealth, as mentioned was founded in the iron Industry. The County of Kent, like Sussex, was the seat of the iron trade in the Weald, and families with a blood connection to the Hendleys, like the aforementioned Bakers of Cranbrook, the Culpeppers at Goudhurst and later the Fanes at Tonbridge all had interests in that field. The Wallers however, may have been at their original manor at Lamberhurst for at least four generations but the first mention of them there, in connection with the iron industry, was in 1522 when they owned a forge there. They were a family of some wealth and social standing and therefore were deemed as a suitable match for one of Walter Hendley’s daughters.

Elizabeth, being the eldest Hendley daughter may have been the first to marry, and it was William, the great grandson of the aforementioned Richard Waller who she married in 1543/4. William was son and heir of William Waller and his wife Anne Falconer. William’s parents, his father at least, was still living at the manor house at Groombridge, but where the couple lived following their marriage is unknown. Elizabeth was soon pregnant and gave birth to a son - another William. Two more children quickly followed, a second son Walter, named after his maternal grandfather, was born c 1546, and a daughter Margery. History has a habit of repeating itself, and just like her father, who was widowed after five years of his marriage, Elizabeth too found herself a young widow with three young children to bring up following William Waller’s death in 1548. William predeceased his father by six years, his four year old son was heir to Groombridge. William, who would have been his father's heir, must have died as an infant for it was Walter who received Groombridge on the death of his grandfather. Margery, it is stated, also predeceased her mother. Tragedy had struck the family three years earlier when Joan, William's sister and Elizabeth’s sister in law died leaving her husband a widower with two sons and three daughters, you really have to wonder how families coped with such a loss don't you?

Elizabeth, being the eldest Hendley daughter may have been the first to marry, and it was William, the great grandson of the aforementioned Richard Waller who she married in 1543/4. William was son and heir of William Waller and his wife Anne Falconer. William’s parents, his father at least, was still living at the manor house at Groombridge, but where the couple lived following their marriage is unknown. Elizabeth was soon pregnant and gave birth to a son - another William. Two more children quickly followed, a second son Walter, named after his maternal grandfather, was born c 1546, and a daughter Margery. History has a habit of repeating itself, and just like her father, who was widowed after five years of his marriage, Elizabeth too found herself a young widow with three young children to bring up following William Waller’s death in 1548. William predeceased his father by six years, his four year old son was heir to Groombridge. William, who would have been his father's heir, must have died as an infant for it was Walter who received Groombridge on the death of his grandfather. Margery, it is stated, also predeceased her mother. Tragedy had struck the family three years earlier when Joan, William's sister and Elizabeth’s sister in law died leaving her husband a widower with two sons and three daughters, you really have to wonder how families coped with such a loss don't you?

In the medieval world the infant mortality rate was high, a parent could lose their baby at birth, a child could die from an awful illnesses such as the plague, their grown up sons could face an early death in battle, their teenage daughters could die in childbirth, with all this, it is easy to see why these parents would have hearts of stone. The concept of love is totally different today than it was then, leading us to believe that the medieval persons more realistic view of life in was indifference. Where we encourage our children, they promote theirs. Where our young choose to live the single life, our elderly often a lonely one, and the rest of us conform to the 2.5 children average, the medieval family were an extended family. Kinship was formed through family ties, so perhaps we might use the term close or strong bond instead of love. This bond led to a sense of duty, responsibility and loyalty, by the end of 1548 both families had complied with this notion by merging into one when Elizabeth married Joan’s widower George Fane. By the January of 1549, Elizabeth and her children were safely ensconced in the manor house at Badsell.

The Fanes, who by the mid 16th century had established themselves at the manor of Badsell in Tonbridge in Kent, claimed that their ancestor fought at Poitiers in 1356, and for capturing the French king was rewarded with a golden gauntlet - strangely this a story very similar to that of the Wallers, were the Fanes claiming the deeds of the aforementioned Richard Waller the ‘Hero of Agincourt’ altering it to suit themselves? True or not, they incorporated it into their heraldic device - three golden gauntlets on a blue background.

Badsell manor, a few miles north of Coursehorn was originally the property of the de Clare family; their tenant, in 1290, was one Gilbert of Badeshell. The family of Culpepper are thought to have held this manor at some point, however by the beginning of the reign of Henry VIII Badsell was held by the Stidulf family whose heiress was Agnes, she married Richard Fane, the one time steward of Tonbridge Castle. Richard and Agnes's son and heir was the aforementioned George Fane.

Badsell manor, a few miles north of Coursehorn was originally the property of the de Clare family; their tenant, in 1290, was one Gilbert of Badeshell. The family of Culpepper are thought to have held this manor at some point, however by the beginning of the reign of Henry VIII Badsell was held by the Stidulf family whose heiress was Agnes, she married Richard Fane, the one time steward of Tonbridge Castle. Richard and Agnes's son and heir was the aforementioned George Fane.

By the time of Elizabeth's marriage to George Fane, Henry VIII had been dead a year, his son, Edward VI was king, and the country was on the brink of religious turmoil that had roots in Henry’s early reign. Events of the intervening years culminated in a number of rebellions such as Kett's Rebellion and the Prayer Book Rebellion in 1548 and 1549 respectively. The blame for these rebellions were laid firmly at the door of Edward Seymour. Seymour, the brother of Henry VIII’s third wife, was in favour of religious reform and against the system of enclosure which affected the livelihood of those living and working on the land, however Seymour's ideas for social reform were frowned upon by the likes of Elizabeth's second cousin John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland. A number of Elizabeth’s ancestors were rebels as far back as the Wars of the Roses and the early part of the Tudor period, however in the following years their actions took a different form as they stood their ground against the new religion and were fined, and their estate forfeited for recusancy as a result.

As Lady Fane, Elizabeth had responsibility for the care of eight children whose ages ranged from ten, to just a few months old, a prospect quite daunting for us, but in the Tudor period families were much larger. The marriages of these children were often arranged while they were young, although the marriage did not take place until the child was at least sixteen - the average age for women being twenty-five, men were a little older. The responsibility of bringing up her own three children was Elizabeth’s alone; she would, most certainly, have had a say in the upbringing of her step-children, so how much input did she have in securing their future? Now, six centuries later, it is easy to see how much influence Elizabeth actually did have, we now know that four out of her five step-children married members of her own family. Katherine, George Fanes eldest daughter married Walter Roberts, Elizabeth's second cousin, Thomas the elder son married her niece Elizabeth Culpepper, and Mary married John Ashburnham, another of her cousins, and Thomas, George Fanes youngest son would marry, albeit later in life, her widowed younger sister Ellen. Only Bridget would marry out of the family, her husband would be Charles Bolles of Haugh in Lincolnshire.

From 1548, Elizabeth had settled into the Fanes moated manor at Badsell while George was occupied with the concerns of a country gentleman; there are no records of his dealings either locally or nationally. However, the Fanes would take steady steps up the social ladder, and by 1556 George had reached the lofty heights of Sheriff of Kent, a position he held for a second term the following year. Their climb was no doubt linked to their accumulating wealth, thus enabling George to seek important positions for his two sons. It was not all plain sailing however as Thomas Fane, along with his cousin Henry, were involved in Wyatt’s Rebellion, was sentenced to death but later reprieved. As for Walter Waller, Elizabeth’s own son, he pursued a military career captaining a regiment in the Netherlands under professional soldier Thomas Morgan.

Elizabeth's marriage to George Fane lasted twenty-four years until his death in 1572, and for two years after she continued to live at their manor house at Badsell until the marriage of her elder stepson to Mary Neville, the daughter of Henry Neville, Baron Bergavenny. Thomas would go on to make Badsell his main residence.

Elizabeth would spend her widowhood loved and admired by all who knew her at the rectory in the Kent village of Brenchley. In 1530, Brenchley was part of the manor of Barnes and had been the property of Cardinal Wolsey but confiscated on his death. By 1563 the rectory was the property of William Waller, and it was granted as as Elizabeth's dowry on his death. It was in this house that she would live in until her own death in 1596.

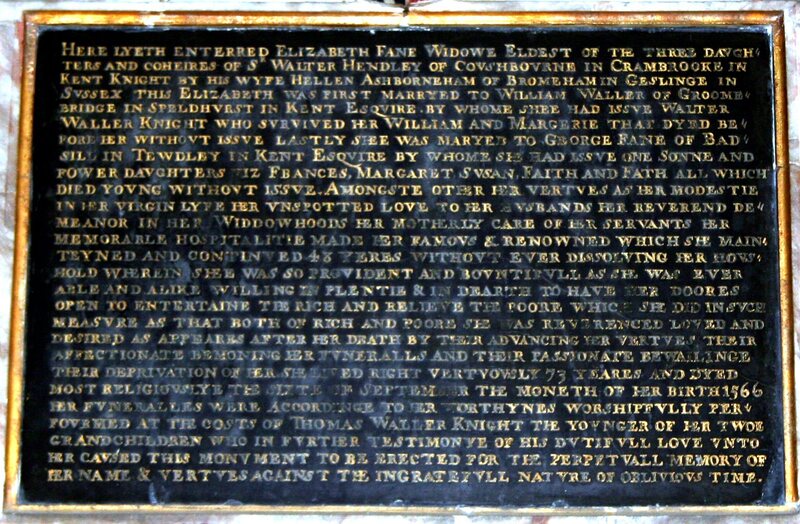

Elizabeth, it seems was a goodly woman, and an account of character can be found on a memorial plaque in All Saints Church in Brenchley.

Elizabeth, it seems was a goodly woman, and an account of character can be found on a memorial plaque in All Saints Church in Brenchley.

Here lyeth enterred Elizabeth Fane widowe eldest of the three davghters and coheires of Sr Walter Hendley of CovBhrovrne in Crambrooke in Kent knight by his wyfe Hellen Ashborneham of Brornebam in Geslinge in Svssex this Elizabeth was first marryed to William Waller of Groomebriclge in Speldhvrst in Kent Esqvire by whome she had issve Walter Waller Knight who svrvived her William and Margerie that dyed before her withovt issve lastly shee was maryed to George Fane of Badsill in Tewdley in Kent Esqvire by whome she had issve one sonne and fower davghters viz. : Frances, Margaret, Svsan Faith and Path all which died yovng withovt issve. Amongste other her vertves as her modestie in her virgin lyfe her vnspotted love to her hvsbauds her reverend demeanor in her widdowhoods her motherly care of her servants her memorable hospitalitie made her famovs and renowned which she mainteyned and coutinved 48 yeres withovt ever dissolving her hovshold- wherein shee was so provident and bovntifull as she was ever able and alike willing in plentie and in dearth to have her doores open to entertaine the rich and relieve the poore which she did in svch measvre as that both of rich and poore she was reverenced loved and desired as appeares after her death by their advancing her vertves their affectionate bemoning her fvneralls and their passionate bewailinge their deprivation of her she lived right vertvovsly 73 yeares and dyed most religiovslye the sixte of September the moneth of her birth 1566 her fvneralles were accordinge to her worthynes worshipfvlly perfovrmed at the cost of Thomas Waller knight the yovnger of her twoe grandchildren who in fvrther testimonye of his dvtifvll love vnto her cavsed this monvment to be erected for the perpetvall memory of her name and vertves against the ingratefvll nature of oblivious time.

In Brenchley's parish register it is written "1596, September the 20th day was buried the Right Worshipful Mrs. Fane, widow."

By the time of Elisabeth's death, Henry VIII daughter, Elizabeth I, had been on the throne for thirty-eight years, she had not married and the succession continued to be an issue. Francis Drake had died, and the Spanish had sent a second Armada to invade. The last Tudor monach died in 1603 unmarried and without issue, and England would have a new monarch in the form of James I. The Stewart dynasty had begun.

NB: The date of Elizabeth's death, as carved in the memorial is 1566, this is incorrect.

In Brenchley's parish register it is written "1596, September the 20th day was buried the Right Worshipful Mrs. Fane, widow."

By the time of Elisabeth's death, Henry VIII daughter, Elizabeth I, had been on the throne for thirty-eight years, she had not married and the succession continued to be an issue. Francis Drake had died, and the Spanish had sent a second Armada to invade. The last Tudor monach died in 1603 unmarried and without issue, and England would have a new monarch in the form of James I. The Stewart dynasty had begun.

NB: The date of Elizabeth's death, as carved in the memorial is 1566, this is incorrect.