|

New

Opportunities |

As the country woke to welcome in the new year, the residence of the City of York rose to find the Duke of York’s head had been sliced from his body and placed on a pike at the very top of Micklegate Bar. In a pitiless act of humiliation, it was plain to see what Margaret of Anjou was saying when she ordered a paper crown placed on his head.

With the death of York and following the terms of the Act of Accord, Edward Earl of March would now take his place as heir to the throne of England, but it was inevitable that the queen would want to see her sons right to the throne restored. Margaret was an ambitious and committed woman.

Margaret of Anjou is described by Polydore Vergil as

‘A woman of sufficient forecast, very desirous of renown, full of policy, council, comely behaviour, and all manly qualities …’

Making her way to Scotland to meet with the widowed Scottish queen Mary of Guelders Margaret was determined to get what she wanted, and if handing back Berwick upon Tweed meant getting it then so be it. When all the papers are signed Berwick upon Tweed became part of Scotland, and it would not be until 1482 when Richard, Duke of Gloucester retook the town that it would return to England.

Margaret headed to London and the incarcerated Henry VI, and as the Lancastrian forces made their way southwards, they passed through villages such as Grantham, Stamford, and Huntingdon, it is said many people took refuge among the fenlands through fear of the advancing army. Of this force the monks at Crowland abbey wrote:

“as they had been paynims, or Saracens and no Christian men”

Margaret of Anjou is described by Polydore Vergil as

‘A woman of sufficient forecast, very desirous of renown, full of policy, council, comely behaviour, and all manly qualities …’

Making her way to Scotland to meet with the widowed Scottish queen Mary of Guelders Margaret was determined to get what she wanted, and if handing back Berwick upon Tweed meant getting it then so be it. When all the papers are signed Berwick upon Tweed became part of Scotland, and it would not be until 1482 when Richard, Duke of Gloucester retook the town that it would return to England.

Margaret headed to London and the incarcerated Henry VI, and as the Lancastrian forces made their way southwards, they passed through villages such as Grantham, Stamford, and Huntingdon, it is said many people took refuge among the fenlands through fear of the advancing army. Of this force the monks at Crowland abbey wrote:

“as they had been paynims, or Saracens and no Christian men”

It was in Gloucester, with John Tuchet, Walter Devereux, William and Richard Herbert and Roger Vaughan of Tretower, that Edward celebrated the Christmas of 1460. It was on the 2nd of January at Shrewsbury that he received the news of the deaths of both his brother and father at Wakefield, the treatment of their bodies must have been a source of great distress, it was one enraged young man that headed out of Wales towards Herefordshire.

It is at this point that the existence of the two contemporary Thomas Vaughan’s, with parallel careers, confuses things somewhat, both men would now begin to become important to Edward and their names begin to appear in official documents. ‘Our’ Thomas Vaughan may have proved his worth to Edward after Ludford or while he was with the king in Calais, the other Thomas Vaughan’s place in court could be seen as a payment of a debt to his dead father, but it was probably a continuation of his family's allegiance, Edward needed the support of his Welsh allies and the Vaughans were, as previously mentioned, linked by blood and marriage to the Herbert, Devereux and the Tuchet/Audley families.

William Herbert and Roger Vaughan were among the men who followed Edward into England, there is no mention of either of Thomas Vaughan’s being present.

One man who joined forces with Edward was William Hasting, he brought a large contingent to join Edward’s army. If the Crowland chronicler was correct when he wrote that many English people feared this Lancastrian army, then it would not be too hard to believe that protecting his properties in the midlands was Hasting prime motive. It is at this point that Hasting makes his first real appearance in history, Hastings had been at Ludlow in support of the Duke of York, but had not been in the Coventry parliament. Having obtained a pardon it is likely that he returned to his home of Ashby de la Zouch or Kirkby Muxloe where he probably stayed until he heard of the Lancastrian advance. Whether Hastings was fast-tracked due solely to his involvement at Mortimer’s Cross is not known but what is known is that he and Edward struck up a close friendship that lasted until Edward’s death in 1483.

When and where Hastings forces joined Edwards to intercept Jasper Tudor who was marching into England from Wales is not known, but the two armies met not too far from Wigmore at Mortimers Cross, and it was in this battle that the future king would give those around him a glimpse of the man he was set to be. The appearance in the sky the night before the battle of a Parhelion was, to Edward, a visual representation of the Holy Trinity and that God was on his side. It has been said of Edward that he was not particularly superstitious, but his men were and Edward possessed the presence of mind to use the three bright suns to his advantage. Edward would show he possessed courage and military skill as well as intelligence.

It is at this point that the existence of the two contemporary Thomas Vaughan’s, with parallel careers, confuses things somewhat, both men would now begin to become important to Edward and their names begin to appear in official documents. ‘Our’ Thomas Vaughan may have proved his worth to Edward after Ludford or while he was with the king in Calais, the other Thomas Vaughan’s place in court could be seen as a payment of a debt to his dead father, but it was probably a continuation of his family's allegiance, Edward needed the support of his Welsh allies and the Vaughans were, as previously mentioned, linked by blood and marriage to the Herbert, Devereux and the Tuchet/Audley families.

William Herbert and Roger Vaughan were among the men who followed Edward into England, there is no mention of either of Thomas Vaughan’s being present.

One man who joined forces with Edward was William Hasting, he brought a large contingent to join Edward’s army. If the Crowland chronicler was correct when he wrote that many English people feared this Lancastrian army, then it would not be too hard to believe that protecting his properties in the midlands was Hasting prime motive. It is at this point that Hasting makes his first real appearance in history, Hastings had been at Ludlow in support of the Duke of York, but had not been in the Coventry parliament. Having obtained a pardon it is likely that he returned to his home of Ashby de la Zouch or Kirkby Muxloe where he probably stayed until he heard of the Lancastrian advance. Whether Hastings was fast-tracked due solely to his involvement at Mortimer’s Cross is not known but what is known is that he and Edward struck up a close friendship that lasted until Edward’s death in 1483.

When and where Hastings forces joined Edwards to intercept Jasper Tudor who was marching into England from Wales is not known, but the two armies met not too far from Wigmore at Mortimers Cross, and it was in this battle that the future king would give those around him a glimpse of the man he was set to be. The appearance in the sky the night before the battle of a Parhelion was, to Edward, a visual representation of the Holy Trinity and that God was on his side. It has been said of Edward that he was not particularly superstitious, but his men were and Edward possessed the presence of mind to use the three bright suns to his advantage. Edward would show he possessed courage and military skill as well as intelligence.

The battle itself lasted into the afternoon, eventually, the Lancastrian troops were pushed back and retreated southwards, many of their men lost their lives drowning in the freezing water as they crossed the River Lugg, Jasper Tudor realised his cause was lost and fled back to Wales. Shortly after the battle Edward heard of the capture of Owen Tudor, he called on his Welsh ally Roger Vaughan and ordered him to Usk Castle, where it is said Tudor was held captive. Owen Tudor was summarily executed, and beheaded in Hereford market square, it was Roger Vaughan who swung the axe. Edward was a king in the making, for now, there would be those whose indiscretions he could tolerate but not when it came to avenge the deaths of those he held dear, and Edward struck, just like John Clifford had at Wakefield. Vengeance is a word often used to explain and justify violence, and the violent actions of John Clifford, Edward IV and later Jasper Tudor were an act of permitted vengeance, and as long as this kind of action is sanctioned by the king and carried out by one of his nominated officers it was not seen as murder.

With his father and brother's deaths avenged Edward and his forces made their way to join the forces of Richard Neville in an attempt to prevent Margaret of Anjou from claiming back her husband and London itself.

With hindsight, Warwick should not have taken Henry VI along with him on his march northwards, he should have left him in London guarded by William Bonville and Thomas Kyriell, the two men who were responsible for him at St Alban’s, but he didn’t. The reason for this, it has been suggested, was that Warwick was overly confident, and considered himself invincible, perhaps he even thought that the meeting between his forces and that of Margaret's was a forgone conclusion, a win for the Yorkist. Warwick was hoping to block Margaret’s way along the northern route to St Albans but this backfired and her troops approached by the north west route. The clash of York and Lancaster took place on the 17th of February 1461, at St Albans, but this time, unlike the previous battle, the result was not a victory for York but a Lancastrian victory. By the end of the day and dusk had settled, Richard Neville’s Yorkist force had been defeated, the king was lost and both Bonville and Kyriell had lost their heads in what Cornish antiquarian, A L Rowse, calls the blooding of Edward of Lancaster, the Prince of Wales.

With his father and brother's deaths avenged Edward and his forces made their way to join the forces of Richard Neville in an attempt to prevent Margaret of Anjou from claiming back her husband and London itself.

With hindsight, Warwick should not have taken Henry VI along with him on his march northwards, he should have left him in London guarded by William Bonville and Thomas Kyriell, the two men who were responsible for him at St Alban’s, but he didn’t. The reason for this, it has been suggested, was that Warwick was overly confident, and considered himself invincible, perhaps he even thought that the meeting between his forces and that of Margaret's was a forgone conclusion, a win for the Yorkist. Warwick was hoping to block Margaret’s way along the northern route to St Albans but this backfired and her troops approached by the north west route. The clash of York and Lancaster took place on the 17th of February 1461, at St Albans, but this time, unlike the previous battle, the result was not a victory for York but a Lancastrian victory. By the end of the day and dusk had settled, Richard Neville’s Yorkist force had been defeated, the king was lost and both Bonville and Kyriell had lost their heads in what Cornish antiquarian, A L Rowse, calls the blooding of Edward of Lancaster, the Prince of Wales.

Including Thomas Kyriell, lying among those who perished at St Albans and who death in one way or another affected Thomas Vaughan’s was Robert Poynings and John Grey of Groby in Leicestershire. It was John's son Richard who would be executed alongside Vaughan at Pontefract in 1483 and his widow, Elizabeth would make an adventurous marriage that would bring this family more wealth and power than they ever dreamed of, but it will also bring the Yorkist dynasty to its knees.

After St Albans things moved fast. Margaret of Anjou arrived at the city's gates but had been turned away, she ordered her troops to retreat and prepared to fight another day. After Edward heard of Warwick’s defeat he and Richard Neville joined forces arriving in London to face a gathered crowd who demanded that Edward take the throne.

On the 4th March King Henry VI was deposed and Edward was declared King within days he was heading towards the Yorkshire village of Towton.

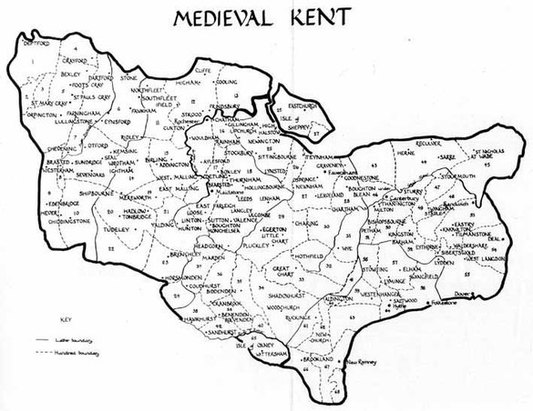

While high-ranking nobles were crossing the length and breadth of the county fighting in one battle after another, men like Thomas Vaughan were falling over each other in what you could call a dignified land grab. Following the execution of Henry’s treasurer Thomas Browne in the Siege of the Tower of London in July 1460, we can see Vaughan doing just that, his major concern was getting his hands on Browne’s estates, all of which were in the County of Kent.

By the time of the aforementioned siege, Thomas Vaughan would probably be approaching his fortieth birthday, in the years that passed I wonder how many men Vaughan could truly call a friend. The modern idea of friendship in all probability did not really exist, medieval ‘friendship’ was based on loyalty but things could change overnight. Medieval loyalties were fragile, what was beneficial one day may not be the next, and therefore trusting someone, I imagine, was something a medieval man did very rarely and even then with caution.

Friend or acquaintance, Thomas Vaughan would profit greatly from Thomas Browne’s misfortune.

Thomas Browne was probably about ten years older than Vaughan and had been employed in Henry’s Exchequer from at least 1426, and they both had close contact with the Beaufort family, so maybe it is through this Beaufort connection they met. Browne had been steward to Cardinal Henry Beaufort in four manors he owned, and we know Vaughan had been in the pay of the Beaufort household as a young boy, but this is rather a tenuous link, however, Vaughan's links to other important men under Lancastrian rule is proven, these men were Kentish gentlemen, Sir John Scott, Richard Haute, John Fogge and more importantly George Browne. Browne become Vaughan step son, Scott and Fogge would be involved with Vaughan in an administrative capacity and Richard Haute would be associated with Vaughan via the care of Edward IV’s son at Ludlow. All five men would eventually be connected by marriage and their landholdings in Kent.

On the 4th March King Henry VI was deposed and Edward was declared King within days he was heading towards the Yorkshire village of Towton.

While high-ranking nobles were crossing the length and breadth of the county fighting in one battle after another, men like Thomas Vaughan were falling over each other in what you could call a dignified land grab. Following the execution of Henry’s treasurer Thomas Browne in the Siege of the Tower of London in July 1460, we can see Vaughan doing just that, his major concern was getting his hands on Browne’s estates, all of which were in the County of Kent.

By the time of the aforementioned siege, Thomas Vaughan would probably be approaching his fortieth birthday, in the years that passed I wonder how many men Vaughan could truly call a friend. The modern idea of friendship in all probability did not really exist, medieval ‘friendship’ was based on loyalty but things could change overnight. Medieval loyalties were fragile, what was beneficial one day may not be the next, and therefore trusting someone, I imagine, was something a medieval man did very rarely and even then with caution.

Friend or acquaintance, Thomas Vaughan would profit greatly from Thomas Browne’s misfortune.

Thomas Browne was probably about ten years older than Vaughan and had been employed in Henry’s Exchequer from at least 1426, and they both had close contact with the Beaufort family, so maybe it is through this Beaufort connection they met. Browne had been steward to Cardinal Henry Beaufort in four manors he owned, and we know Vaughan had been in the pay of the Beaufort household as a young boy, but this is rather a tenuous link, however, Vaughan's links to other important men under Lancastrian rule is proven, these men were Kentish gentlemen, Sir John Scott, Richard Haute, John Fogge and more importantly George Browne. Browne become Vaughan step son, Scott and Fogge would be involved with Vaughan in an administrative capacity and Richard Haute would be associated with Vaughan via the care of Edward IV’s son at Ludlow. All five men would eventually be connected by marriage and their landholdings in Kent.

In 1450 however, Thomas Vaughan may have had little contact with any of these men prior to his arrival in London to take up his role as Master of the King’s Ordnance, but once he was established in the city he must have been spending time with John Scott and John Fogge and other city aldermen, more than likely

entertaining at his house at Garlek.

When the Cade rebellion kicked off, and while Vaughan was realising the danger the king's ordnance was in, Scott, Fogge, and one Robert Horne’s financial support, all told they paid over £300, helped suppress the Kentish Rebellion, and as defectors to the Yorkist regime in 1460, their support was seen as crucial to the Yorkist success in Kent. Scott became deputy to John Wenlock as Chief Butler of Sandwich and gained the Lieutenancy of Dover under Richard Neville. Sir John Fogge had been a squire in the household of Henry VI and following the Battle of Towton was a royal councillor and a leading royal associate in Kent. The Horne family too were connected by marriage, and through them, we can view how close these Kentish families were. The Horns were a prominent Kentish family who progenitor was Henry Horne, Sheriff of Kent whose daughter was Joan, wife of William Haute the younger whose brother and cousin was Richard Haute. Joan was also the sister-in-law to John Fogge who was married to William’s sister Alice and kinswoman to Eleanor Browne, niece to George Browne. It was Henry’s son Robert, I believe to be the above-mentioned Robert Horne, he is stated as being a distinguished soldier, but following his imprisonment in Newgate by Cade’s men (he was only freed after paying a large ransom,) died in 1461.

Through the aforementioned Hautes, these men and their families came into close contact with the Woodville families and as we have seen this led to later successful careers in the reign of Edward IV and to a lesser degree Richard III.

The Haute family owe their success in the main to the marriage, in 1429 of William Haute to Joan Woodville, sister of Richard Woodville. Two Richard Hautes feature at this time, and history has confused both as it has done with the two Thomas Vaughan's, both Richards were active in Wales and both were prominent in royal circles. The elder of the two’s mother was the aforementioned Joan Woodville, he had married into the Tyrell family and was Lieutenant of the Tower from 1471 to 1473 and captured, along with George Browne, for his part in Buckingham's Rebellion. He was pardoned in the March of 1484. The younger of the two was either cousin or second cousin to the elder, it was this Richard who was arrested along with Vaughan at Stoney Stratford in 1483. Standing on the peripheries was another Kentish noble, long-time Yorkist supporter Robert Poynings, he and a handful of the Kentish gentry had joined Cade's rebellion. Robert Poynings was said to have been Jack Cade’s carver and sword bearer, but his motives for taking part are suspect. Poynings, like Vaughan’s interests, involved estates in Kent, and it can be said that his reasons for taking part were purely personal rather than for the greater good, I cannot imagine him shedding a tear when his stepbrother, William Crowmer’s head was placed on a spike and paraded through the streets of London.

Poynings too would be connected to Vaughan via marriage, albeit only for eight months.

George Brown was the closest to Vaughan in terms of family, within three months of his father’s execution Browne would be Vaughan’s stepson, a relationship that Browne detested. George Browne’s career was not that of his fathers, he held minor positions with the county of Kent and Surrey but it was not until his marriage to Elizabeth Paston, the widow of Robert Poynings, who had been killed at St Albans in 1461, that he had some political and social clout. Browne became stepfather to Poynings seven-year-old son Edward and had control of the boy's inheritance until he came of age. Browne became a member of Edward IV's household and had a close association with George, Duke of Clarence. Robert Poynings used the law to attempt to regain property and lands from Crowmer and Henry Percy, and George Browne used the law to regain the Browne estates, spending time and money trying to claim back the forfeited lands that had passed to Vaughan and Thomas Fogge and this may be the reason, with regard to and in connection with the Poyning estate, held by the Percy family that influenced George's decision to join Buckingham’s rebellion in 1483.

entertaining at his house at Garlek.

When the Cade rebellion kicked off, and while Vaughan was realising the danger the king's ordnance was in, Scott, Fogge, and one Robert Horne’s financial support, all told they paid over £300, helped suppress the Kentish Rebellion, and as defectors to the Yorkist regime in 1460, their support was seen as crucial to the Yorkist success in Kent. Scott became deputy to John Wenlock as Chief Butler of Sandwich and gained the Lieutenancy of Dover under Richard Neville. Sir John Fogge had been a squire in the household of Henry VI and following the Battle of Towton was a royal councillor and a leading royal associate in Kent. The Horne family too were connected by marriage, and through them, we can view how close these Kentish families were. The Horns were a prominent Kentish family who progenitor was Henry Horne, Sheriff of Kent whose daughter was Joan, wife of William Haute the younger whose brother and cousin was Richard Haute. Joan was also the sister-in-law to John Fogge who was married to William’s sister Alice and kinswoman to Eleanor Browne, niece to George Browne. It was Henry’s son Robert, I believe to be the above-mentioned Robert Horne, he is stated as being a distinguished soldier, but following his imprisonment in Newgate by Cade’s men (he was only freed after paying a large ransom,) died in 1461.

Through the aforementioned Hautes, these men and their families came into close contact with the Woodville families and as we have seen this led to later successful careers in the reign of Edward IV and to a lesser degree Richard III.

The Haute family owe their success in the main to the marriage, in 1429 of William Haute to Joan Woodville, sister of Richard Woodville. Two Richard Hautes feature at this time, and history has confused both as it has done with the two Thomas Vaughan's, both Richards were active in Wales and both were prominent in royal circles. The elder of the two’s mother was the aforementioned Joan Woodville, he had married into the Tyrell family and was Lieutenant of the Tower from 1471 to 1473 and captured, along with George Browne, for his part in Buckingham's Rebellion. He was pardoned in the March of 1484. The younger of the two was either cousin or second cousin to the elder, it was this Richard who was arrested along with Vaughan at Stoney Stratford in 1483. Standing on the peripheries was another Kentish noble, long-time Yorkist supporter Robert Poynings, he and a handful of the Kentish gentry had joined Cade's rebellion. Robert Poynings was said to have been Jack Cade’s carver and sword bearer, but his motives for taking part are suspect. Poynings, like Vaughan’s interests, involved estates in Kent, and it can be said that his reasons for taking part were purely personal rather than for the greater good, I cannot imagine him shedding a tear when his stepbrother, William Crowmer’s head was placed on a spike and paraded through the streets of London.

Poynings too would be connected to Vaughan via marriage, albeit only for eight months.

George Brown was the closest to Vaughan in terms of family, within three months of his father’s execution Browne would be Vaughan’s stepson, a relationship that Browne detested. George Browne’s career was not that of his fathers, he held minor positions with the county of Kent and Surrey but it was not until his marriage to Elizabeth Paston, the widow of Robert Poynings, who had been killed at St Albans in 1461, that he had some political and social clout. Browne became stepfather to Poynings seven-year-old son Edward and had control of the boy's inheritance until he came of age. Browne became a member of Edward IV's household and had a close association with George, Duke of Clarence. Robert Poynings used the law to attempt to regain property and lands from Crowmer and Henry Percy, and George Browne used the law to regain the Browne estates, spending time and money trying to claim back the forfeited lands that had passed to Vaughan and Thomas Fogge and this may be the reason, with regard to and in connection with the Poyning estate, held by the Percy family that influenced George's decision to join Buckingham’s rebellion in 1483.