Changing sides didn't affect Trollope, although he was considered a traitor and had a price placed on his head, Edward IV offered a £100 reward to anyone who killed "certain named enemies of the House of York", which included Trollope. Andrew Trollope died in battle at Towton in 1461 and Wenlock died at Tewkesbury, supposedly at the hand of Edmund Beaufort punished for a mistake that cost many Lancastrian soldiers their lives. I wonder did these men expect to feel the sharpness of a blade on their necks, not in the name of justice but in revenge. John Wenlock is forever labeled Wenlock the Prince of Turncoats because of the number of times he defected.

|

There are a number of men who fought in the Wars of the Roses who defected from one side to another, Andrew Trollope changed his allegiance from the Yorkists to the Lancastrians after the standoff at Ludlow Bridge in 1459 is one notable traitor, another John Wenlock did the same in 1471 following Richard Neville from the Yorkist camp to assist Margaret of Anjou in her quest. Changing sides didn't affect Trollope, although he was considered a traitor and had a price placed on his head, Edward IV offered a £100 reward to anyone who killed "certain named enemies of the House of York", which included Trollope. Andrew Trollope died in battle at Towton in 1461 and Wenlock died at Tewkesbury, supposedly at the hand of Edmund Beaufort punished for a mistake that cost many Lancastrian soldiers their lives. I wonder did these men expect to feel the sharpness of a blade on their necks, not in the name of justice but in revenge. John Wenlock is forever labeled Wenlock the Prince of Turncoats because of the number of times he defected. Sometimes however there are those who changed sides and did well for themselves, one of them was Sir John Sutton, a long-time supporter of the Lancastrians. Sutton had accompanied the body of Henry V from France to England and was chief mourner and standard bearer at his funeral. He held a number of positions under Henry VI. At Blore Heath, along with his son Edmund, had commanded a wing of the Lancastrian army and had survived despite the battle being a Yorkist victory. Sutton was taken prisoner and later released. He fought at Northampton for Henry, but following the king's capture, he switched sides. Despite all this, John Sutton climbed the ladder to success under Edward IV and Richard III, fighting for the last Yorkist banner at Bosworth. William Dugdale wrote of John Sutton "he was faithful to King Henry VI, yet he did so comply with King Edward IV, when he obtained the crown, that he received many great favours and rewards from that new Sovereign."

0 Comments

On the 27th September in 1442, John de la Pole, son of William de la Pole and Alice Chaucer was born. John, known as the Trimming Duke, for reasons I am yet to fathom, was married in the February of 1450, at the age of seven, to the six year old to Margaret Beaufort, but this marriage was annulled. This was probably due to the disgrace of his father's downfall and exile, but there was more to it that that. In 1453 Henry VI deemed that Edmund Tudor, who was twelve years her senior, would be a better husband for Margaret. Her vast inheritance, her bloodline and a need to back up the succession were contributing factors. When John became Duke of Suffolk three months following the murder of his father, his family was one of the least wealthy titled families in the country. In 1458 he married Elizabeth, the daughter of Richard Duke of York and Cecily Neville. The fifteen-hundred pounds that she brought to the marriage made little difference to his finances, and most certainly was not a patch on what Margaret would have brought. Although this marriage allied de la Pole to the Yorkist party he is noted as having not shown any true support for either side. However, in 1461 he had made his decision, fighting for the Yorkist at the second Battle of St Albans and at Towton, but like others 'sat on the fence' at Bosworth and managed to survive under Henry VII rule at his home at Winglfield in Suffolk.

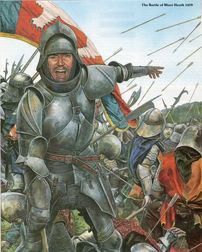

John and Elizabeth were parents to eleven children, he would outlive five of them. The three son who did survive their father were Edmund, William and Richard all would suffer due to their Yorkist blood and all would try their best to oust the Tudor king, but as you probably know they were unsuccessful. On the 29th of April in 1450 at Wingfield John's father prepared himself for exile, in doing so he wrote a heartfelt and moving letter to his eight year son. You can read this here: meanderingthroughtime.weebly.com/wars-of-the-roses-blog/true-and-ever-loving-father The events of the years between 1450 and 1459 can be equated to a giant roller coaster ride, with both sides at differing times, riding the front car. It comes as no surprise that such a high state of tension would eventually come to blows, and it did at St Albans in the May of 1455. St Albans is considered by some to be the first battle of a civil war that has come to be known as the Wars of the Roses. In a battle that lasted just one hour, a number of notable Lancastrian nobles including, Henry Percy, Thomas Clifford, and Edmund Beaufort were killed. After the battle Henry VI was captured, Richard, Duke of York assured Henry of his loyalty and along with the Earl of Warwick accompanied the king to London. Just under two months later, at the beginning of July, the king opened Parliament and following that, Henry, along with his Margaret of Anjou and their son were moved to Hertford Castle. That November saw the Duke of York appointed as Protector for a second time, and just like the first protectorate it was short, it ended in the last week of February 1456, but York remained an important member of the Royal Council. However, three very troubled years ensued, and at the end of which the Duke of York, with Richard Neville as his enforcer, would make his play for the crown of England. In those intervening years, two battles took place The Battle of Ludford Bridge in the October of 1459 and the Battle of Blore Heath on the 23rd September 1459, where Margaret of Anjou is said to have watched from the tower of a local church. Following the Yorkist victory at St Alban's and with the king's health unpredictable Margaret had been determined to rid the country of any Yorkist who she considered was a threat to her and who would take her husband's crown. At the same time, the Duke of York had decided it was time action was taken and had given an order that his forces and that of Richard Neville, the Earl of Salisbury should assemble at Ludlow. It was while Salisbury's forces were marching south from Middleham, that they were intercepted by a Lancastrian force under James Tuchet, Baron Audley, and John Sutton, Baron Dudley. The geography of Blore Heath battlefield featured a large wood but was mainly open heath with Hempmill Brook running along the bottom of the battlefield. Archaeological work suggests that the brook may have been dammed at the time and this would have made the terrain wet and soft. The battlefield straddles what is now the A53, a road that runs southwest across the country. In 1459 the layout of the land favoured the Lancastrian's for they outnumbered the Yorkist forces by at least two to one, however, in the first attack the Lancastrian forces lost men when they were forced out from their position by a planned retreat by the Earl of Salisbury whose force doubled back ensnaring the enemy. In the second attack, Audley's men successfully crossed the brook on whose muddy banks many of the Lancastrian force had perished in the previous attack, it was in this second attack that Audley lost his life. Edward Halls writes: The Earl of Salisbury, which knew the sleights, strategies and policies of warlike affairs, suddenly returned, and shortly encountered with the Lord Audley and his chief captains, ere the residue of his army could pass the water. The fight was sore and dreadful. The earl desiring the saving of his life, and his adversaries coveting his destruction, fought sore for the obtaining of their purpose, but in conclusion, the earl's army, as men desperate of aid and succour, so eagerly fought, that they slew the Lord Audley, and all his captains, and discomfited all the remnant of his people... Following Audley's death, John Sutton took command and the battle continued for the rest of the day, eventually, the Lancastrian assault collapsed and many on the losing side would flee through the water and mud, pursued and then slain. The total combined forces at Blore Heath have been estimated at between eleven and nineteen thousand. The Yorkist losses were few, however, the Lancastrian's deaths numbered about two thousand.

Three months later the wheel of fortune would turn again this time favouring Henry VI's forces. On the 12th October, the Yorkists regrouped at Ludford Bridge but discouraged by the size of the Lancastrian army they retreated when they found themselves opposite their enemy across the River Teme. During the night many of York's army deserted, and this was followed by a retreat the next morning, the Duke of York and his son Edmund of Rutland headed for Ireland, Richard Neville, his father and York’s eldest son Edward, later Edward IV fled to Calais. Following Blore Heath John Sutton, Audley's commander was captured but later released and eventually made Treasure of Henry VI's household. He was a survivor of the Wars of the Roses, in later years he was pardoned by both Edward IV and Henry VII. The Yorkist leader, the Earl of Salisbury, would lose his life just over a year later at the Battle of Wakefield. . . For a number of years, depending on who was on the throne at the time, England had been on good terms with either France or Burgundy, using this to his advantage Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick proposed to the September council that a peace treaty be signed with Louis XI of France. Also some members of the council had agreed with Warwick’s suggestion that it was high time Edward IV was married. Louis thought so too, an English alliance with France was far better for him than a Burgundian alliance, eventually Warwick succumbed to a bit of flattery and bribery and put it to Edward that Bona of Savoy would be a perfect match. In the September of 1464, during a discussion of this subject, and to the surprise of many, Edward indicated that the idea of marriages was indeed a good one, he never batted an eyelid at the suggestion of a French bride, even though he himself favoured Burgundy. After a long silence, he finally relayed the fact that he had already made his choice and in fact he had already married one Elizabeth Grey, a member of the lowly Woodville family of Northamptonshire. Edward, as Paul Murray Kendall quite rightly points out, had succumbed to lust and not with a weak, mild mannered virgin either, but with a strong willed widow with two young sons, and with eight siblings to boot! Edward had undertaken all this without the knowledge of one man who was so instrumental in bringing him to the throne - Richard ‘the Kingmaker’ Neville.

Edward’s news was shattering, Warwick had pledged Edward in marriage to the sister of the queen of France. Edwards irresponsible behaviour humiliated Warwick and ruined his plans, his prestige both home and abroad was in tatters, and to say that Warwick was enraged would be an understatement, the dagger of betrayal had cut too deep and it was a wound that would never heal. On the 8th September 1483, Edward of Middleham, the only child of Richard III and his wife Anne Neville was invested as the Prince of Wales in a spectacular ceremony in the city of York. The Crowland Chronicler writes of the occasion that Edward was "elevated to the rank of Prince of Wales, with the insignia of the golden wand, and the wreath upon the head; while, at the same time, he (Richard) gave most gorgeous and sumptuous feasts and banquets." Don't be fooled by the writer's tone, the chronicler was not writing of this event in a positive light, far from it. The chronicler went on to state that the celebrations were only for effect to 'gain the affections of the people' and paid for with the amassed wealth entrusted to Richard, as executor of his late brother Edward IV's will - taken it was written 'the very moment that he (Richard) had contemplated the usurpation of the throne.' What is interesting about this text is that there is a mention that the so called Princes in the Tower were actually in the Tower of London whilst the investiture took place - "in the meantime, and while these things were going on, the two sons of king Edward before-named remained in the Tower of London," surprisingly the writer doe's not seize the opportunity to relay to his readers exactly what happened to the two boys after the investiture seeing that most people thought Richard had 'done away with them' towards the end of the summer of 1483. The chronicler also goes on to state that Edward IV's daughters should leave the sanctuary of Westminster, and 'go in disguise to the parts beyond the sea; in order that, if any fatal mishap should befall the said male children of the late king in the Tower, the kingdom might still, in consequence of the safety of his daughters, some day fall again into the hands of the rightful heirs." The important word in that sentence is IF, doesn't this suggests that nobody, including the writer, knew what happened to the two boys at the time? We should bare in mind that the Crowland Chronicle was written two years after these events took place - the writers were spouting propaganda, words they thought their new king wished to hear, words that would keep them safe in the new Tudor era and by someone who was educated in law and who was privy to information within the royal court. The Benedictine residents of Crowland Abbey had at their head one Lambert Fossdyke who had been Abbot at Crowland since January 1484 and who was a Bachelor of Law and it was such a man with a degree in law who was considered to be the writer of malicious rumors about Richard III. John Russell, Bishop of Lincoln, is commonly thought to be the author but it could just as well have been Fossdyke dictating to one of his monks? Of Edward and Richard's fate there is no evidence, however poor Edward of Middleham would only live another seven months, he died in the April of 1484.

|

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed