|

Margaret Beaufort has had links with the county of Lincolnshire since at least the middle of the 15th century, for instance she is known to have held the Manor of Bourne from about 1445. Following the fall of the House of York, she was granted other Lincolnshire estates such as the manor of Tattershall, which, along with its castle, had been forfeited to the crown in 1471. She also received the manor of Stamford following the death of Cecily Neville in 1495. She must have had some affection for the fenlands because she spent much of her time, when she was married to her third husband, at their castle in the aforementioned manor of Bourne. She is also known to have spent some time in the market town of Boston, her account books show an entry of a payment to a child who played a song for her during a visit - maybe she was entertained in the household of Fredrick and Margaret Tilney in their Skirbeck home. She may well have even attended a service at the recently built St Botolph's Church and been shown the newly carved choir stalls and misericords. The Tilney's were an important family in Boston at the time of Margaret's visit, later their great granddaughter would become Henry VIII's fifth wife. Despite what many think of Henry VII's mother, she was a generous benefactor to churches and abbeys and often kind to those less fortunate that herself and, this is why her emblem of the portcullis can be found dotted around the town. She can also be seen immortalised, albeit quite recently, in a stained glass window in the at St Botolph's.

3 Comments

The names of Richard, Earl of Warwick and George, Duke of Clarence's were never officially mentioned as being part of the 1469/70 uprisings against Edward IV but it is plain to see that Warwick was the puppeteer. Letters, incriminating Warwick, were found in a chest that belonged to the man who led the uprising in Lincolnshire in the March of 1470. Robert Welles letter goes some way back up this fact as does his confession, Wells writes: "I have welle understand my many meagges, as welle from my Lord of Warwicke, and they entended to make grete risinges, as forthorthy as ever I couth understand , to th’entent to make the duc of Clarence king…..Also, I say that had beene the said duc and erls provokings that we at this tyme would no durst have made eny commocion or sturing, but upon there comforts we did what we did”......Also, I say that I and my dadier had often times letters of credence from my said lordes.” It is not hard to imagine what the state of the country was in during these years, anarchy would possibly be a good word to describe it. Following the aforementioned Lincolnshire revolt - the Battle of Empingham or Losecoate Field as it is commonly known, Warwick and Clarence fled the country. They were refused entry into Calais but eventually arrived in the court of Louis XI of France. While under the protection of the French king Warwick set about organising the restoration of Henry VI to the throne of England and the marriage his daughter Anne to Henry's son Edward. An invasion force was soon bound for England's shores and they landed in the West Country between the 9th and 13th of September 1470. Warwick found that his brother John, the Marquess of Montage, had abandoned the Yorkist cause and he also soon learned that the king had left England. While most were troubled by the events of 1469 and 1470 the triumphant Richard Neville was in his element as he later placed the crown of England, once again, on the head of Henry VI. Released from the Tower of London, the poor man’s physical health was weak and his mental health clearly unstable. As these two men stood together it was obvious to everybody who was in charge. Real power was now in the gauntleted hand of Richard, Earl of Warwick, the King’s Lieutenant of the Realm.

This is a print of an engraving by John Raffe of Micklegate Bar in York from a painting by English artist William Westall. Westall is most famous for the work he produced in Australia. In 1800 he was asked by Joseph Banks to serve as a landscape and figure painter aboard HMS Investigator, under Lincolnshire born Matthew Flinders. By 1829 Westall was back in England working for publisher Rudolf Ackermann. Westall’s illustrations were used in educational publications and he also produced over a hundred drawing for Great Britain Illustrated from where I believe this print originates.

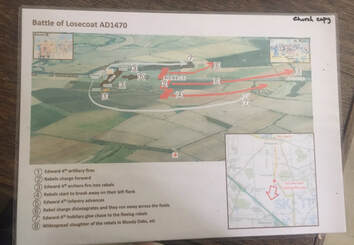

I will be definitely keeping it and having it framed despite the fact it was the place where Richard Duke of York’s head was placed following the Battle of Wakefield. The Battle of Losecoat Field, which took place on the 12th March 1470, occurred ten years after Edward IV had brought the Lancastrian's to their knees at Towton, even so, Edward was still concerned with Lancastrian plots, he was, it seems, blind to the fact that Richard Earl of Warwick was cunning and we can be sure that Warwick was clever enough not to be seen to be involved in plotting the downfall of the House of York. This battle, also known as the Battle of Empingham, was not simply a matter of York vs Lancaster. The situation was complex and confusing and involved minor rebellions, local land disputes and Warwick's machinations. The trigger for the battle itself was a private dispute between Lincolnshire land owners, Sir Thomas Burgh of Gainsborough Hall and Sir Richard Welles of Eresby, that had ended in violence and criminal damage. Both men had been called to London to account for their actions, Edward was forgiving and lenient, and ordered them back to Lincolnshire to put an end to their differences. Richard Welles left this meeting with the king unnerved, it may have been the threat that if Welles did not sort out this private feud, then he would come up the Lincolnshire to do it himself. In Lincolnshire, Welles son Robert was using his father's summons to London to add weight to Robin of Redesdales claim that Edward was ready to execute anyone who had been involved in the revolts in Yorkshire the previous year. Redesdale, the second of that name, was using this threat to incite fear and rebellion among the populous. In the hours and days following the meeting the situation deteriorated and for whatever reason, the feud or the escalating violence, Edward was forced to ride to Lincolnshire to put a stop to the rebellion. The resulting battle was fought on the fields in Rutland, not far from the village of Empingham, on a site that straddles the Great North Road. Losecoat was a victory for Edward, and a death sentence for both Robert Welles and his unfortunate father. The battle is named after the place where many of the rebel army fled, abandoning their surcoats for fear of retribution. All that really remains of this small, but significant battle, is a small wood, seen in the image on the right, with just a few hundred trees called Bloody Oaks. Neither the Earl of Warwick or George, Duke of Clarence's names were never officially mentioned, but it is plain to see that Warwick was the puppeteer. Letters, incriminating Warwick, that were found in a chest that was recovered among Welles belongings goes someway back up this fact. Following Welles arrest and in his confession he writes “ I have welle understand my many meagges, as welle from my Lord of Warwicke, and they entended to make grete risinges, as forthorthy as ever I couth understand , to th’entent to make the duc of Clarence king…..Also, I say that had beene the said duc and erls provokings that we at this tyme would no durst have made eny commocion or sturing, but upon there comforts we did what we did”......Also, I say that I and my dadier had often times letters of credence from my said lordes.” It is not hard to imagine what the state of the country was in, anarchy would possible be a good word to describe it. While most were troubled by the events of 1469 and 1470, the triumphant Richard Neville was in his element as he later placed the crown of England, once again, on the head of Henry VI. Released from the Tower of London, the poor man’s physical health was weak and his mental health clearly unstable. As these two men stood together it was obvious to everybody who was in charge. Real power was now in the gauntleted hand of Richard, Earl of Warwick, the King’s Lieutenant of the Realm.

King Edward IV became unwell in the Easter of 1483 and false news of his death and uncertainty as to who would take the throne was the talk in the major towns and villages of the realm. The city of York had received news on the 6th April 1483 (three days early) that the king was dead, convinced of this fact the city held a Requiem Mass the following day. Uncertainty about Edward’s replacement was also a concern, especially in the county of Lincolnshire. John Gigur, warden of Tattershall College in Lincolnshire, wrote to the Bishop of Winchester: "I beseche you to remember in what jeopardy youre college of Tateshale stondyth in at this day; for nowe oure Soveren Lord the Kyng ys ded we wete not hoo schal be oure Lord nor hoo schal have the reule aboute us."

My photographs show all of what remains of Tattershall's Old Collage, where John Gigur wrote to the Bishop of Westminster in 1483 voicing his concerns. Standing proudly in the Fenlands of Lincolnshire are the ruins of the Abbey of Crowland, and as autumn brings its misty evenings, or winter its frozen crisp mornings, standing among the abbeys broken arches you cannot help but think of the forthcoming Christmas festivities. At the beginning of December, Crowland Abbey joins in the fun of Christmas just like any other religious establishment, usually in the first week of December it has its Christmas Craft and Food Fare when mince pies are eaten and maybe a drink of mulled wine is sampled. On the 6th December in 1484, the second Christmas of King Richard III's reign and just like today people celebrated, for this day was St Nicholas's saints day. On that day, our ancestors believed this Saint Nicholas brought gifts such as nuts, fruits and marzipan sweets, and with these gifts the ability to foretell the events of the following year. While most of the Fenland community where knocking back the Christmas ale, Crowland Abbey was not so festive. Within the abbey the monks were busy with local and national affairs, on one hand they were trying to keep talk of a local dispute quiet and on the other being quite vocal in its criticism of Christmas in the court of King Richard III. Whoever it was that put ink to parchment, had much to say on the subject of the shenanigans going on at Richard's Christmas parties. The writer of the famous Croyland Chronicle states that he was unable to account for many of the activities in the court at this time “because it is shameful to speak of them” even Queen Anne and Elizabeth of York were considered "vain" because they had more than one party outfit. Richards best buddy, Bishop Thomas Langton, joined these medieval party poopers by stating "sensual pleasure holds sway to an increasing extent.’ What on earth did this mean? Did Richard kiss the lovely Ann more than once under the misletoe I wonder? Not one of the writers made any attempt to elaborate on any of the events they were writing about. All the criticisms of Richards "wild parties" came from the clergy who were very quick to point out that Richard saw himself as a "good, learned, serious and virtuous man" while also pointing out that he had called his brothers court "licentious and morally corrupt." The University of Leicester School of Historical Studies quite rightly pointed out that compared with the wild parties that were held at Rome during the reign of Pope Alexander VI, the English court under Edward IV and Richard III was a 'model of virtue.’ Surely, even the pious, like Richard, should not be frowned upon for having a good time, obviously there was more to these statements than meets the eye. Perhaps these people were just a tad miffed and just bit disgruntled at not to being invited. Did they watch from a distance or listen enviously to tales told the following morning of how Catesby, Lovell and Ratcliffe danced in silly animal party hats or King Richard drank way too ale and threw iced cakes at the clergy. In reality of course, all these damning words were written years later. Those who pooh poohed the kings festivities were not irritated because a invitation hadn't landed on their door mat, they were spouting propaganda, words they thought their new

king wished to hear, words that would keep them safe in the new Tudor era. History suggests that the events at court in 1484, as written in the Croyland Chronicles, were written two years later in 1486, by someone who was educated in law and who was privy to information within the court. The Benedictine residents of Crowland Abbey had at their head one Lambert Fossdyke who had been Abbot at Crowland since January 1484 and who was a Bachelor of Law and it was such a man with a degree in law who was considered to be the writer of these malicious rumors about Richard III. John Russell, Bishop of Lincoln, is commonly thought to be the author but it could just as well have been Fossdyke dictating to one of his monks? |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

- Home

-

My Family Stories

- Bustaine of Braunton: Introduction

- Hunt of Barnstaple Introduction >

- Lakeman of Mevagissey >

- Meavy Introduction >

- Mitchell of Crantock: An Introduction >

- Mohun of Dunster: Introduction >

- Purches of Hampshire and Cornwall >

- Scoboryo of St Columb Major >

-

Thomas Vaughan: An Introduction

>

- Smith of Barkby Introduction >

- Taylor Introduction >

- Tosny of Normandy >

- Toon of Leicestershire: Introduction >

- Underwood of Coleorton Introduction

- Umfreville of Devon >

- Other Families

- History Blog

- Wars of the Roses Blog

- The Ancestors

- A to E

- F to J

- K to O

- P to T

- U to Z

- Hendley of Coursehorne Kent

- Pigott Family of Whaddon Buckinghamshire

- Links

- Contact

- Umfreville test

RSS Feed

RSS Feed