The Second Battle of Lincoln can be viewed through my photographs taken at a reenactment in 2014.

|

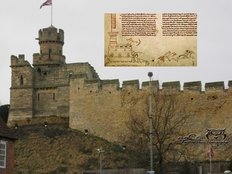

The Battle of Lincoln, the second of that name in a period known as the Baron's War, was one of the most influential battles fought on England's soil. The 20th May 1217, saw Louis VIII's French forces under the Count of Perche attack the garrison at Lincoln Castle which was held by soldiers who were loyal to Henry III. English forces, under the command of William Marshall, arrived in Lincoln from the north, eventually securing the castles north gate and forcing the surrender of the French army. The battle took place in the area around Lincoln's castle, its cathedral and what is now Steep Hill, and today marks eight hundred years since this battle took place. My photograph below shows the Observatory Tower of Lincoln Castle where I have added a medieval illustrated text that tells the story of the battle. As you can see they are both from the same viewpoint, it is quite eerie to think that the illustrator of the medieval image may have stood on the exact same spot where I took the photo from 798 later. In the illustration, you can see a bowman perched high in the observatory tower firing at the retreating army. The Second Battle of Lincoln can be viewed through my photographs taken at a reenactment in 2014. Lincoln Castle garrison stands to defend this important fortification from forces loyal to Prince Louis, led by the Count of Perche. Meanwhile, William Marshal proceeded to the section of the city walls nearest the castle, at the north gate. The entire force of Marshal's crossbowmen led by the nobleman Falkes de Breaute assaulted and won the gate. Perche's forces did not respond but continued the castle siege. The north gate was secured by Marshal's main force, while Breaute's crossbowmen took up high positions on the rooftops of houses. Volleys of bolts from this high ground caused rapid death, damage, and confusion among Perche's forces. Then, in the final blow, Marshal committed his knights and foot soldiers in a charge against Perche's siege After six hours Perche was offered a surrender, but instead fought to the death as the siege collapsed into a scattered rout. Those of Louis' army who were not captured fled Lincoln out the south city gate to London.

0 Comments

16th May 1643The Cornish town of Stratton, that lies close to the boarder with Devon, was a manor owned by my ancestors in the early 12th century, its history, and theirs is quite fascinating. Stratton was the head of its hundred (a division of the county for judicial purposes) and was an important stannary town in the north of Cornwall. It had a thriving agricultural and leather trade. By the 17th century there was little to show that my ancestors ever lived there, however on the 16th May 1643, a civil war battle, the Battle of Stratton, took place at the base of Stamford Hill, less than a mile north of the family's castle. The battle raged for most of the day, but by the end of it Henry Grey, Earl of Stamford, had lost half of his forces enabling the Cornish Royalist army to march across the border from Cornwall to Devon. It was a Royalist victory, and a quite remarkable one considering the three thousand Royalist troops, under Sir Ralph Hopton, faced Grey's Parliamentarian army that numbered over five and a half thousand. By July, Hopton had lead his forces in two more battles, one at Crediton and one at Landsdowne, where Hopton was injured. A year later he successfully defended Devizes from an attack by William Waller's forces and two years after that he had taken up a defensive position in the Devon town of Torrington, a battle that marked the end of Royalist resistance in the West Country.

Henry Grey's failure at Stratton and the surrender of the city of Exeter after a three month siege effectively ended his career as a Parliamentary commander. Almost eighty years into the Hundred Years War, on Friday, October 25, 1415, Saint Crispin's Day, Henry V of England met the French army led by the Constable Charles d'Albret in Northern France, near the present-day town of Agincourt. Estimates are that the English were outnumbered from 2 to 1 to as much as 4 to 1. Most of the English were archers and dismounted knights, while most of the French were mounted knights. Some crossbow mercenaries were part of the French force too. But they had a limited range compared to the long bow and also took a lot longer to reload and re-shoot their weapon.

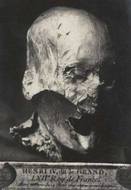

Before the battle, which Henry was actually trying to avoid, he ordered the archers to find and sharpen both ends of a six-foot wooden stick. These were then hammered into the soft ground of the plain where the battle ultimately took place. It rained the night before the battle, and there was mud and soft earth all throughout the battleground. The wooden stakes were pointed outwards, towards the French lines. When the French knights on horseback charged the English archers, many of the horses would not advance through the thicket of sharpened points. Archers picked off horses and knights from a distance and at close range. French knights and men at arms were trapped by their heavy armour in the mud, becoming easy prey for the outnumbered English. the French who had not been killed or stuck in the melee fled. Some say that the French knights had issued threats that, if they caught any archers from the English side, they would cut off their inside fingers, so they could not pull back a bowstring. To taunt these French knights, the English archers held up their middle fingers to show they still had them. Noble French prisoners, who could have been sold for rich ransoms, were ordered killed after the French retreat. Henry was worried these prisoners would rise up and attack the English from behind if, or when, another wave of French knights appeared to engage his forces. On the 14th May 1610, Henry IV of France was assassinated by Francois Ravaillac, a Catholic radical, who stabbed the king when the coach he was travelling in was caught up in congestion on the Rue de la Ferronnerie in Paris. In 1793, an eyewitness reported that when the royal tombs at the Abbey of Saint Denis were destroyed, the embalmed and perfectly preserved body of Henry was displayed in state in the Basilica, and for many days people filed in silence to pay their respects. A story of the treatment of the French kings remains suggests that in 1793, at the height of the French Revolution, Henry's body was exhumed and posthumously beheaded, revolutionary soldiers even taking cuttings from his beard. Henry's head is said to have been sold in the 1920's and remained in private ownership. Eventually the skull resurfaced, and in 2010 a digital facial reconstruction was undertaken and as you can see from the image below the finished article certainly looks king like. However, a recent study on the DNA taken from the skull found a genetic discrepancy between the head and three living male relatives leading to the conclusion the head didn't come from Henry at all or anybody in the royal lineage. It seems that the story of the ill treatment of Henry IV's body during the French Revolution was propaganda and to use a term that is popular at the moment - fake news.

Henry IV of France was known as Good King Henry, he was a military leader and politician who put an end to the religious wars that had torn France apart. A Protestant, he had converted to Catholicism to unite his subjects for whom he had great compassion. He showed much sympathy for the poorest in his realm of whom he said "If God keeps me, I will make sure that no peasant in my realm will lack the means to have a chicken in the pot on Sunday!" On the 14th May 1264, Henry III forces were defeated by the armies of Simon de Montfort at the Battle of Lewes in Sussex. This battle was one of two main battles in the conflict known as the Second Barons War and at this point Montfort was riding high. King Henry III is said to have been intelligent and quick to master the problems of administration and government, he was also seen a "uncomplicated, almost naive man, and a lover of peace," yet all this is hardly mentioned, historians preferring to write about Simon de Montfort who not only stole Henry's crown but also his limelight. The dissatisfaction of Henry's barons culminated in the Second Barons War in 1263. It was Simon de Montfort who lead the rebellion against Henry, and after the Battle of Lewes both the king and his son Edward, later Edward I, were captured and it was de Montfort who ruled in his name. Eventually, de Montfort lost the support of many of Henry's disaffected barons, this along with Edward escaping his captors and raising an army was the beginning of the end for de Montfort. After the Battle of Evesham, Montfort met a grizzly end and Henry regained his throne.

Image Credit Lewes Town Council On the 1st May in 1118 occurred the sudden death of Matilda of Scotland. Following Matilda's burial at Westminster Abbey there were rumors of miracles at her tomb. This is no surprise, Matilda built hospitals, abbeys and gave generously to the church. She was fond of literature, music and the arts.

In the Hyde Chronicle, a study of England and Normandy at the time of the Norman Conquest thought to have been written by William of Blois, there is a reference to Matilda: "From the time England first became subject to kings, out of all the queens none was found to be comparable to her, and none will be found in time to come, whose memory will be praised and name will be blessed throughout the ages." Saintly is a word you could use to describe Matilda, not only for her good works, but the fact she was the wife of Henry I. Henry I was, to put it politely, a bit of a ladies-man, having numerous illegitimate offspring and as many mistresses, I have often wondered if Henry's philandering was the reason Matilda's children were born in the first four years of their eighteen years of marriage. Queen Matilda is buried on the right hand side of the original Shrine of St Edward the Confessor at Westminster Abbey. There is no memorial for her. You can read more on this on my blog at meanderingthroughtime.weebly.com/history-blog/matilda-of-scotland |

Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

After ten years in the workplace I became a mother to three very beautiful daughters, I was fortunate enough to have been able to stay at home and spend my time with them as they grew into the young women they are now. I am still in the position of being able to be at home and pursue all the interests I have previously mentioned. We live in a beautiful Victorian spa town with wooded walks for the dog, lovely shops and a host of lovely people, what more could I ask for.

All works © Andrea Povey 2014. Please do not reproduce without the expressed written consent of Andrea Povey. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed