King Edward’s grief at the loss of his wife is well known as is the fact that at each place his queen's body rested on her journey to London he erected crosses, all different and all beautifully ornate. The first one placed was at St Catherine’s, sadly nothing but a stump remains, and this can be found in the grounds of Lincoln Castle.

At Harby, a chantry chapel was established in 1294 where prayers were said for the queen's soul and this was done until the dissolution, however the building itself survived until 1877.

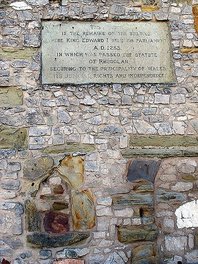

The aforementioned Chantry Chapel once stood behind the iron railings, on the spot where the above was taken.

| |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed