|

Louis XI of France believed that the end justified the means, in 1475 he bought off Edward IV for a payment of 75,000 crowns with the promise of 50,000 a year and the marriage of his son to Edward’s daughter - peace with England meant that he could sort out his problems with Burgundy. His reign saw the beginning of the end of feudalism and he left France in a better position than that of his father. However he had his critics, for modernising the French army with the use of the Swiss idea of a permanent royal infantry and no temporary contracts Machiavelli called him shortsighted and imprudent. Regardless of the fact that he achieved much in his reign, he was overall generally disliked. Louis is famously known by a number of nick-names, Louis the Purdent for his skills in the world of diplomacy, and for his scheming and plotting he was known as the Universal Spider. Loving a good conspiracy did him no good in the end though, he died at the end of August 1483, of what you could argue was the over use of his little grey cells - a brain hemorrhage.

0 Comments

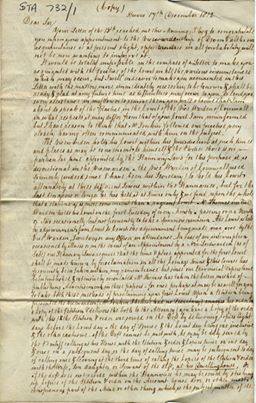

The word Stannary means 'belonging to tin mines' and is taken from the Latin word Stanum. The areas in Cornwall, where tin was extracted, were known as Stannaries and the law that affected them were known as Stannary Law. These Cornish Stannaries form part of the Duchy of Cornwall, an estate which was created by Edward III in 1337 when he granted his son, Edward, the Black Prince Duke of Cornwall. Tin mining in Cornwall is ancient, and employed men in remote and outlying areas away from the main towns, and therefore they had their own rules and regulations. The early Earls and Dukes of this distant county reaped great rewards from mining and since early times the mines and the men working them have been protected by the crown. This institution had its its head wardens who were governed by the Lord Warden of the Stannaries. The writ appointing the Lord Warden covered the "just and ancient customs and liberties of miners, smelters and merchants of tin." The first to hold this title was William de Wrotham who was given this title on the 20th November 1197 during the reign of King Richard I. In 1198, juries of miners at Launceston, stood before Wrotham to swear by the law and practice of the tin mines. Over the years, Royal Charters issued by Edward I in 1305, Edward IV in 1466, and Henry VII in 1508 have changed and added to the laws within the Stannaries. King John, often seen as a selfish and greedy king, was not slow to see the attraction of the Cornish tin industry. In 1201 he issued the first charter to the Stannaries. By 1214, production of tin had risen to six hundred tons, the result of this saw many men, who once worked on the land, move to mining. One of the clauses of Magna Carta was that no lord shoud lose the service of his men whether he dug tin or not. Henry III confired his fathers charter, and the Stannaries soon had their own taxation, no acknowledged lord and were 'a law unto themselves.' By the end of the 13th century the Stannaries were under the control of Richard, the second son of King John and his son Edmund as the Earls of Cornwall. In 1225, Richard, at just sixteen, was granted the County of Cornwall and all its tin works, and following that the Earldom of Cornwall. Later Edward I granted privileges to tinners to be tried by their own courts and benefit from the exemption of taxation. The above image records one John Gurney’s appointment as Vicewarden of the Stannaries for Devon and explains the differences between the courts in Cornwall and Devon.

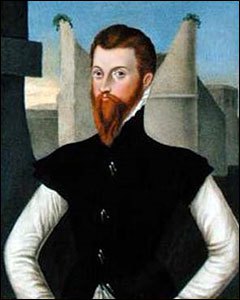

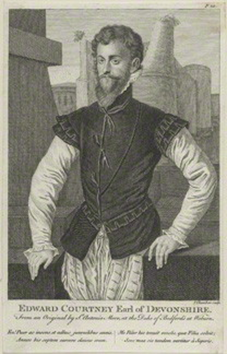

On the 18th September 1556, Edward Courtenay, Earl of Devon died in Padua, Italy. A number of 'ailments' have been suggested as the cause of the Earl's death, fever, syphilis, falling down a flight of stairs and even poisoning. Edward Courtenay had Yorkist blood flowing through his veins, his grandmother was Catherine of York, daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. Catherine had married William Courtenay, Earl of Devon by 1496. In 1538, at the age of twelve, Edward joined his parents Henry Courtenay, Marquess of Exeter and Gertrude Blount in the Tower of London. His father was suspected of being in cahoots with Reginald Pole and Gertrude was accused of encouraging the traitorous behaviour of her husband. Henry Courtenay was executed at the end of 1539 and his wife was released at the start of the following year, however, Edward was to remain a prisoner, he would remain in the Tower of London for fifteen years. He was finally released on the 3rd August 1553. After his release his fortunes improved, he was considered as a possible husband for Henry VIII's daughter Mary and when she married Phillip of Spain he set his sights on Elizabeth who would later become Elizabeth I. Edward and Elizabeth were suspected of being involved in the rebellion of Thomas Wyatt and others who were fearing persecution under Mary's rule. They were both imprisoned, but when no evidence was found they were both released and Courtenay fled the country. I've always wondered why this family, as a possible threat to the Tudor dynasty, were not hunted down like that of the family of George Duke of Clarance's for instance, Henry VIII had no qualms about seeing off the aged Margaret Pole and Henry VII had executed Edward's grandfather. Maybe, this new generation didn't consider the Yorkists as much of a treat anymore? Words on the engraving of Courtenay above state: En! puer ac insons et adhuc juvenilibus annis, Annos bis septem carcere clausus eram, Me pater his tenuit vinclis quae filia solvit, Sors mea sic tandem vertitur a superis. Behold! a guiltless boy and still in his youthful years, during twice-seven years had I been shut in prison, the father held me in these chains which the daughter released, thus at last is my fate being changed by the gods above." Interestingly, in this engraving Courtenay stands in front of a crumbling castle, whats the significance of that do you think?

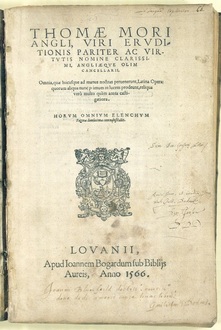

When ever the subject of the Princes in the Tower comes up, there are always lots of interesting responses regarding the find of skeletal remains of two children under a set of steps in the Tower of London which many still consider to be that of the two sons of Edward IV who disappeared in 1483. These remains eventually ended up in an urn in Westminster Abbey with the following inscription 'Here lie interred the remains of Edward V King of England, and Richard, Duke of York, whose long desired and much sought after bones, after above an hundred and ninety years, were found by most certain tokens, deep interred under the rubbish of the stairs that led up to the Chapel of the White Tower, on the 17th of July in the year of our Lord 1674. Charles the second, a most merciful prince, having compassion upon their hard fortune, performed the funeral rites of these most unhappy princes among the tombs of their ancestors, anno domini 1678.' But it is the remains found under a stair case by workmen in 1674 that are still thought to be that of the two princes Edward and Richard of Shrewsbury. Why is that? What is interesting is the intense focus on this set of remains, they are only one, among a number of children's remains, that have been found in the Tower of London over the years that are said to be of Edward and Richard. Others include remains found when Sir Walter Raleigh was imprisoned in the Tower, remains found when the tower's moat was drained in the mid nineteenth century and in 1789 the two small child size coffins that were found walled up in a 'hidden space' next to the vault holding the coffins of Edward V and his Elizabeth his queen. The real answer to this question is quite simple and pretty straight forward. Sir Thomas More's in his The History of Richard III says it was so. More writes ....."About midnight (the sely children lying in their beddes) came into the chamber, and sodainly lapped them vp among the clothes so be wrapped them and entangled them keping down by force the fetherbed and pillowes hard vnto their mouthes, that within a while smored and stifled, theyr breath failing, thei gaue vp to god their innocent soules into the ioyes of heauen, leauing to the tormentors their bodyes dead in the bed." but here's the interesting bit...... ..... "Whiche after that the wretches parceiued, first by the strugling with the paines of death, and after long lying styll, to be throughly dead: they laide their bodies naked out vppon the bed, and fetched sir Iames to see them. Which vpon the sight of them, caused those murtherers........... to burye them at the stayre foote, metely depe in the grounde vnder a great heape of stones....... Than rode sir Iames in geat haste to king Richarde, and shewed him al the maner of the murther, who gaue hym gret thanks." Thomas More is not only responsible for the fact that Charles II and everybody else considers these remains to be that of the two princes but that King Richard III from then on was the princes murderer. The 'story' that the remains are of Edward and Richard, stems partly from the work of Professor William Wright and Dr George Northcroft who published their findings in ‘The Sons of Edward IV. A re-examination of the evidence on their deaths and on the Bones in Westminster Abbey’ This work ought be treated with caution, DNA aside, I wonder how it can be suggested that they were, in life, the princes, if they never established the sex of the skeletons? In 1986 it was pointed out that a couple of important facts from the study were not mentioned. Firstly, there were indications in "existing and unerupted teeth" that suggested that one of the skeletons was a female and secondly the age gap between the two remains were less than three years of the princes. IF these two boys they met their deaths at the Tower, who in their right minds would place the bodies under the noses of all who were in the present at the time, without being seen and within a limited time frame? Others feel the same, suggesting there were better ways to get rid of the bodies than to hide them somewhere in the Tower itself.

I don't know why More wrote what is written here, or what his motives were, I don't know what happened to the two princes in the summer of 1483, they may well have been murdered, but equally they might not have been. What I do know is that it has never been proved that the two sons of Edward IV were dead at all. I also don't believe it is their remains at Westminster Abbey. |

Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

After ten years in the workplace I became a mother to three very beautiful daughters, I was fortunate enough to have been able to stay at home and spend my time with them as they grew into the young women they are now. I am still in the position of being able to be at home and pursue all the interests I have previously mentioned. We live in a beautiful Victorian spa town with wooded walks for the dog, lovely shops and a host of lovely people, what more could I ask for.

All works © Andrea Povey 2014. Please do not reproduce without the expressed written consent of Andrea Povey. |

- Home

-

My Family Stories

- Bustaine of Braunton: Introduction

- Hunt of Barnstaple Introduction >

- Lakeman of Mevagissey >

- Meavy Introduction >

- Mitchell of Crantock: An Introduction >

- Mohun of Dunster: Introduction >

- Purches of Hampshire and Cornwall >

- Scoboryo of St Columb Major >

-

Thomas Vaughan: An Introduction

>

- Smith of Barkby Introduction >

- Taylor Introduction >

- Tosny of Normandy >

- Toon of Leicestershire: Introduction >

- Underwood of Coleorton Introduction

- Umfreville of Devon >

- Other Families

- History Blog

- Wars of the Roses Blog

- The Ancestors

- A to E

- F to J

- K to O

- P to T

- U to Z

- Hendley of Coursehorne Kent

- Pigott Family of Whaddon Buckinghamshire

- Links

- Contact

- Umfreville test

RSS Feed

RSS Feed