|

Louis XI of France believed that the end justified the means, in 1475 he bought off Edward IV for a payment of 75,000 crowns with the promise of 50,000 a year and the marriage of his son to Edward’s daughter - peace with England meant that he could sort out his problems with Burgundy. His reign saw the beginning of the end of feudalism and he left France in a better position than that of his father. However he had his critics, for modernising the French army with the use of the Swiss idea of a permanent royal infantry and no temporary contracts Machiavelli called him shortsighted and imprudent. Regardless of the fact that he achieved much in his reign, he was overall generally disliked. Louis is famously known by a number of nick-names, Louis the Purdent for his skills in the world of diplomacy, and for his scheming and plotting he was known as the Universal Spider. Loving a good conspiracy did him no good in the end though, he died at the end of August 1483, of what you could argue was the over use of his little grey cells - a brain hemorrhage.

0 Comments

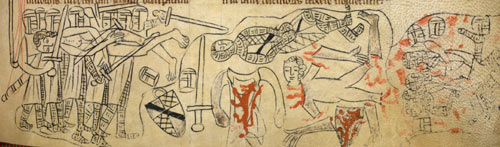

Held at the British Library, and entitled The Death of John Chandos this image gives us the impression that Chandos died in battle. However, his death did not occur exactly as it is depicted. Of his death, the medieval French chronicler Froissart wrote

"it was a great pity he was slain, and that, if he could have been taken prisoner, he was so wise and full of devices, he would have found some means of establishing a peace between France and England" Sir John Chandos was born in the County of Derbyshire. Chandos is believed to have been the mastermind behind three English victories during the Hundred Years War, the Battle of Crecy, Poitiers, and Auray, and his death on the 31st of December of 1369 is said to have been regretted by both the English and the French. Unusual for a man of his day, Chandos had no noble title, his family connections were to land held from the time of the Norman Conquests, and they may well have been pre-Norman landowners. He was a founding knight of the Order of the Garter and a close personal friend of Edward, the Black Prince. For services rendered to the crown, Chandos was made Lieutenant of France, the vice-chamberlain of England later became Constable of Aquitaine and Seneschal of Poitou. By the middle of the fourteenth century, Chandos had fallen out with the Black Prince and left England to retire to property he held in Normandy. By 1369 Edward had asked Chandos to return, their disagreement of taxation seems to have been forgotten, to join his forces against the French who were busy retaking English territory. Sadly, it was this recall that ended in Chando's death, not in battle as we have seen, but a simple accident. The accident took place after his troops returned from a nighttime skirmish, Chandos returned to camp, where, whilst walking, he managed to entangle himself in his clothing and subsequently slipped on an icy patch and was stabbed in the face by a squire. He was taken to Castle Morthemer but died of his wounds a few days later. Nestling quietly in the Lincolnshire Wolds is the village of Somersby, it was here that poet Alfred Tennyson was born on the 6th of August in 1809. The fourth of twelve children, he was tutored by his father, the Reverend George Tennyson in classical and modern languages. Tennyson attended Louth Grammar School but was eager to leave home due to family problems. He left Lincolnshire in 1827 to attend Trinity College, Cambridge and by 1830 he had published a few poems, in 1832 he published a second volume of work that were not received well. Shocked by so negative reviews Tennyson would not publish another book for nine years. In 1836, he became engaged to Emily Sellwood but financial troubles caused his Emily's family to call off the engagement. The year 1842, was a turning point for Tennyson, his work received great praise and had become popular, by 1850 with the publication of In Memoriam A H H, our local poet became one of Britain’s most popular poets. Tennyson was named Poet Laureate in succession to Wordsworth and in that same year he married Emily Sellwood by whom he had two sons, Hallam and Lionel. By the age of forty one, Tennyson had established himself as the most popular poet of the Victorian era culminating in 1884 with a peerage, after which he was known as Alfred Lord Tennyson. Tennyson died on October 6, 1892, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Today he is the second most frequently quoted writer in the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations after Shakespeare. Tennyson wrote a number of phrases that we use all the time today one being 'Better to have loved and lost, than never to have loved at all' from his In Memoriam and "Theirs not to reason why, theirs but to do and die' from his poem The Charge of the Light Brigade. We must not forget my favourtie work of his The Lady of Shallot. On either side the river lie Long fields of barley and of rye, That clothe the wold and meet the sky; And thro' the field the road runs by To many-tower'd Camelot; And up and down the people go, Gazing where the lilies blow Round an island there below, The island of Shalott. Willows whiten, aspens quiver, Little breezes dusk and shiver Thro' the wave that runs for ever By the island in the river Flowing down to Camelot. Four grey walls, and four grey towers, Overlook a space of flowers, And the silent isle imbowers The Lady of Shalott. Simon de Montfort was French by birth and a year younger than Henry III. In 1248, Henry had appointed Montfort as Governor of Gascony, a mistake that cost Henry dearly. In Gascony, Montfort was disliked, but he was powerful and he abused his position and this forced Henry to intervene. On Montfort's return to England, he perceived Henry as weak and with the barons aching for a fight, it was Simon de Montfort that stepped in to take charge. In 1258 this action culminated in the Provisions of Oxford, a law that served to limit Henry’s power. Henry’s refusal to accept the Provisions of Westminster the following year saw Montfort’s power base grow rapidly, and by 1263 he was all but wearing the crown. On the 14th of May 1264 at the Battle of Lewes, Henry, his son the future Edward I, and Richard, Duke of Cornwall were taken prisoner but a year later the tables were turned, and it was at the Battle of Evesham, on the 4th August in 1265, that Simon de Montfort and his eldest son Henry died a grisly death. The Bishop of Lincoln, Robert Grosseteste, once said to Henry de Montfort: "My beloved child, both you and your father will meet your deaths on one day, and by one kind of death, but it will be in the name of justice and truth." The bishop was right on both counts: Of Henry de Montfort's death, the "first born son and heir, in full view of his father, perished, split by a sword. and Simon himself: "the head was severed from his body, and his testicles cut off and hung on either side of his nose" Bishop Grosseteste was correct.

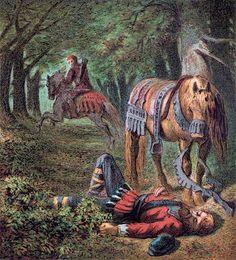

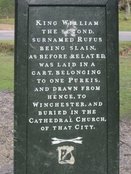

With the arrival of William the Conqueror, many of England's forests were used by the Norman kings for hunting and hawking. The New Forest in Hampshire was one of these. Today, the New Forest is one of the largest remaining areas of open pasture land, heath and forest, and in the 12th century most of England would have looked something like this. It was on the 2nd of August in 1100 that William Rufus, the Conqueror's second son, died whilst hunting, murdered, it has been suggested by Walter Tirel on the orders of William's younger brother the future Henry I. However the Anglo Saxon Chronicle states that the king was slain by one of his own men. Another theory is that he was killed on the order of Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury. There are lots of interesting theories as to who ended the life of the king, and there are even more fascinating reasons why it was done, all have one thing in common though, that is William Rufus was an angry, over confident and nasty man who history deems got what he deserved. As a child I was told by my grandfather that it was an ancestor of ours who found William Rufus on the floor of the forest. Intrigued, I searched among books to see if this was true, and indeed my grandfathers tale has a basis in fact for, legend has it, that a man did come across the dead king and took him to Winchester in his cart, his name was Purkis. My family story may or may not be true, however my grandfathers surname was Purches, and his grandfather's family are all Hampshire born and their surname of Purches is derived from the surname Purkis. Maybe it's a true story after all.

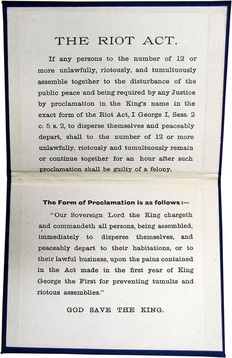

William Rufus remains lie in Winchester Cathedral. As a child, I can remember being told that I would have the "the riot act" read to me for misbehaving, can you? I took it to mean that I'd would be told off for causing trouble. I realised what that term meant even when I didn't exactly understand its origins. After the 1st August 1715, if you and eleven of your mates were hanging around making a nuisance of yourselves, being rather loud and throwing cabbages at a statue of a local dignitary, those in authority would deem that you were 'unlawfully assembled." You could be asked nicely to go home, but if didn't you would be dragged off to the local lock up and eventually find yourself standing in front of the local magistrate. The Riot Act of 1715 went by the rather long title of "An Act for preventing tumults and riotous assemblies, and for the more speedy and effectual punishing the rioters." It was introduced a year earlier when the country was troubled by a number of serious disturbances with the intention of "many rebellious riots and tumults that have been taking place of late in divers parts of this kingdom" and gave the warning "Our sovereign Lord the King chargeth and commandeth all persons, being assembled, immediately to disperse themselves, and peaceably to depart to their habitations, or to their lawful business, upon the pains contained in the act made in the first year of King George, for preventing tumults and riotous assemblies. God save the King." If you chose to ignore this new act you could find yourself imprisoned for a couple of years with just a hammer and large rocks to keep you occupied." The act was read in 1819 at Peterloo in Manchester to a number of people who were peaceful campaigning for

parliamentary reform by magistrates who were panicked at the sight of the crowd. A year later in 1919 in Glasgow the city's sheriff had the 'act' ripped from his hands as he was reading it to a crowd of over ninety-thousand people. The Riot Act soon fell into disuse, however the last time it was read was in 1929 following a bonfire in Chiddingford in Surrey, to one small boy and the attending police officers. |

Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

After ten years in the workplace I became a mother to three very beautiful daughters, I was fortunate enough to have been able to stay at home and spend my time with them as they grew into the young women they are now. I am still in the position of being able to be at home and pursue all the interests I have previously mentioned. We live in a beautiful Victorian spa town with wooded walks for the dog, lovely shops and a host of lovely people, what more could I ask for.

All works © Andrea Povey 2014. Please do not reproduce without the expressed written consent of Andrea Povey. |

- Home

-

My Family Stories

- Bustaine of Braunton: Introduction

- Hunt of Barnstaple Introduction >

- Lakeman of Mevagissey >

- Meavy Introduction >

- Mitchell of Crantock: An Introduction >

- Mohun of Dunster: Introduction >

- Purches of Hampshire and Cornwall >

- Scoboryo of St Columb Major >

-

Thomas Vaughan: An Introduction

>

- Smith of Barkby Introduction >

- Taylor Introduction >

- Tosny of Normandy >

- Toon of Leicestershire: Introduction >

- Underwood of Coleorton Introduction

- Umfreville of Devon >

- Other Families

- History Blog

- Wars of the Roses Blog

- The Ancestors

- A to E

- F to J

- K to O

- P to T

- U to Z

- Hendley of Coursehorne Kent

- Pigott Family of Whaddon Buckinghamshire

- Links

- Contact

- Umfreville test

RSS Feed

RSS Feed