This west country castle was once the ancestral home of the Hungerfords, a family who had sided with the Lancastrians during the Wars of the Roses and were punished for that with execution and the loss of their estates. Castle Farleigh was granted to Richard, Duke of Gloucester, later Richard III, however, in 1473 it was linked with the Duke of Clarence for it was here that Isabel gave birth to Margaret.

Isabel Neville died in 1476 and Clarence was executed two years later, Margaret lived out the rest of her childhood with her paternal cousins in the royal household. Six years following the accession to the throne by Henry Tudor she was married to Richard Pole by whom she would have five children - the four sons were thorns in the sides of Henry VIII. However, Margaret was a member of the young Katherine of Aragon's household during the reign of Henry VII and under Henry VIII she was governess to Henry's daughter Mary. During the troubles between Catherine and Henry and Henry and Mary, Margaret would stay true to their cause.

By the end of 1538, Margaret was in trouble and found herself embroiled in the fall out of the arrests of her sons Geoffrey and Henry Pole on a charge of treason. She was detained at Cowdray Park, the home of the Earl of Southampton. It wasn't long before trumped up charges were brought against her, and she was sent to the Tower where she was kept for just under two years. Poor Margaret was not treated well during her incarceration, the conditions were austere and inadequate for a woman her age let alone her status, the room was cold and damp and she suffered as a result.

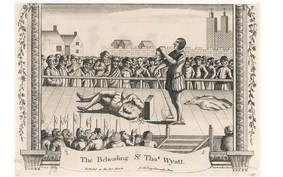

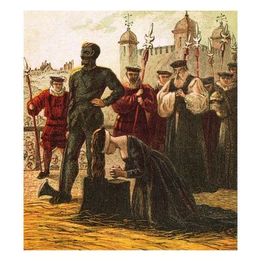

Margaret Pole would die at the hands of an inexperienced executioner on the 27th May in 1541 - she was sixty-eight years old.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed