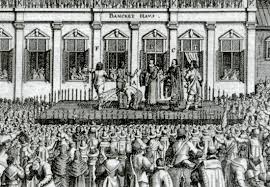

On the 30th King Charles waited inside the Banqueting House in Whitehall for the doors to be opened so that he might make his way to the scaffold that had been erected outside. Maybe there was ice on the windows, as history tells us Charles asked to wear two heavy shirts so that he might not shiver in the cold. Charles did not wish that his people think that he was afraid.

Charles I was beheaded that day - he said:

"... truly I desire their liberty and freedom as much as anybody whomsoever; but I must tell you that their liberty and freedom consist in having of government, those laws by which their life and their goods may be most their own. It is not for having share in government, sirs; that is nothing pertaining to them; a subject and a sovereign are clear different things. And therefore until they do that, I mean that you do put the people in that liberty, as I say, certainly they will never enjoy themselves. Sirs, it was for this that now I am come here. If I would have given way to an arbitrary way, for to have all laws changed according to the power of the sword, I needed not to have come here; and therefore I tell you (and I pray God it be not laid to your charge) that I am the martyr of the people..."

An observer in the crowd said of the execution:

'There was such a groan by the thousands then present as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again’.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed